Idle Words > Talks > Observations on Technology Use in Hong Kong Protests

I was asked to present brief remarks on the situation in Hong Kong at the Stanford Internet Observatory E2E Encryption Workshop on September 12, 2019. These observations are based on the period August 9-September 9, which I spent attending protests and speaking with demonstrators, journalists, students and fellow observers.

The pro-democracy protests in Hong Kong are entering their fourteenth week. Over a thousand people have been arrested, and many protesters have been seriously injured by police. China’s celebration of its 70th birthday is coming up on October 1, and the fifth anniversary of Occupy Central protests is coming up on September 28, so tensions are high.

I will briefly lay out the legal context of the protests, and the threats that protesters face, before I explain the ways they are using social media and messenger apps to coordinate protest within that setting.

Legal Context

Hong Kong is a Special Administrative Region of China, with a high degree of formal autonomy. The territory was ceded to China in 1997 under the “One Country, Two Systems” framework designed to preserve its legal and economic system. By treaty, Hong Kong is supposed to enjoy this special status until 2047.

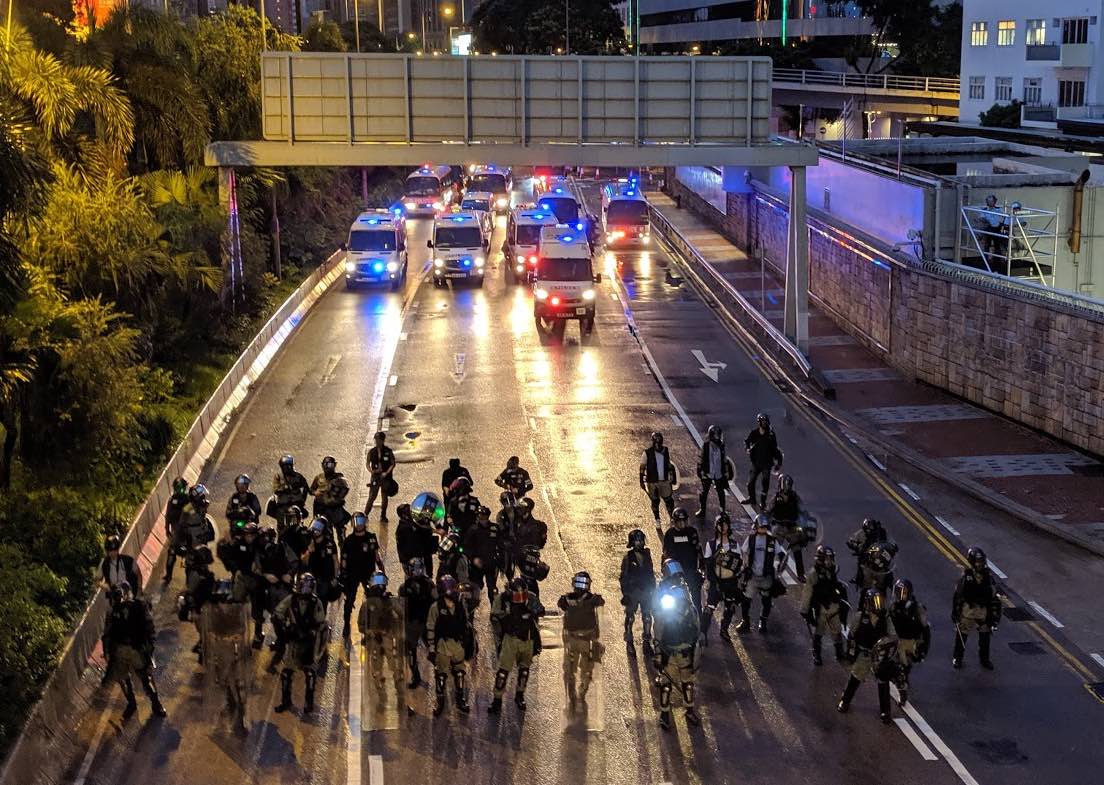

The current protests are a series of clashes between demonstrators and Hong Kong authorities, with behind the scenes pressure but not open interference from Beijing. On one side of the conflict is the Chief Executive and the 30,000 members of the Hong Kong Police Force. On the other side of the conflict is essentially everybody else. Protests on June 9 and 16 drew an estimated 1 and 2 million marchers respectively, in a city of 7 million. So far over 1,000 people have been arrested and protesters have sustained many severe injuries, some inflicted after people were taken into police custody.

While there are pockets of Hong Kongers who support the mainland (like the North Point neighborhood, with ties to Fujian province), the protests enjoy broad social support, in part because indiscriminate police violence has scandalized a society where violence was rare.

It is understood that the Hong Kong police and executive authority respond to directives from Beijing, but the court system in Hong Kong is genuinely independent.

Hong Kong sits outside the Great Firewall, with unrestricted access to the Internet. This is not just a policy choice, but a physical reality; the infrastructure is not in place to quickly expand mainland Chinese internet controls to cover Hong Kong.

It is important to understand the constraints on China. Hong Kong is China’s financial gateway to the global financial system, and that status depends on the continuing independence of Hong Kong’s legal system. Both foreign direct investment and the international banking system rely on Hong Kong because of the strong guarantees offered by Hong Kong courts. Any infringement on the rule of law in Hong Kong by China would have catastrophic results if it scared off foreign firms.

This special status as a financial gateway protects Hong Kong. Corruption at the highest levels of the Chinese Communist Party offers an additional level of protection. Chinese officials rely on a functioning Hong Kong for various forms of money laundering. There is no easy way to buy an Italian villa with renminbi without going through Hong Kong.

So Beijing has a combination of “macroeconomic” and “microeconomic” incentives to leave Hong Kong alone. Direct interference would hurt China’s economy, and the death of Hong Kong as a financial gateway would personally affect large numbers of the elite.

This makes a lot of the Chinese toolkit for dealing with dissent unavailable in Hong Kong. In particular, an Internet blackout, arbitrary detention, extradition to the mainland, or direct use of the People’s Armed Police or PLA would all be unacceptable to international financial interests.

The problem with this protection is that it is brittle. Once China crosses a red line that scares off international capital (like imposing Internet restrictions, or circumventing the courts), there may no longer be a deterrent against other forms of direct interference.

Threats

Hong Kong’s Basic Law guarantees its citizens freedom of speech and freedom of the press. The weak point is freedom of assembly. If police label a gathering of three or more people a riot, it can carry a ten-year jail penalty. The organizers of the 2014 protests served or are serving time on such charges.

China has also been putting enormous pressure on Hong Kong businesses to fire workers who participate in the protests, most publicly at the flagship airline, Cathay Pacific. Similar pressure is being applied to schools now that the school year is under way.

So the biggest threats to protesters are that they will be arrested at a public assembly, or that they will be individually identified from photographs or otherwise. In addition to legal jeopardy, Hong Kong has a culture of doxxing, which does not carry the same stigma as in the US. This is a threat both to protesters and police.

Another threat protesters face is physical attack, both by police at rallies as well as mainland-affiliated thugs who have been allowed to attack individuals with impunity. This has included prominent opposition figures attacked in broad daylight.

Finally, Hong Kong residents and visitors are facing pressure at the Shenzhen boundary crossing, where border guards search devices for any protest-related content. At least one medical school has pulled students from mainland hospitals to avoid subjecting their students to this intimidation.

For whatever reason, Hong Kong authorities have shown themselves reluctant to make mass arrests. They may lack the physical capacity to do it, or have other reasons. The strategy seems to be to arrest enough people to deter the rest. So from the protesters’ side, the goal is to not be one of the 20-150 people arrested at an event.

The threat of mass surveillance is part of a cataclysmic scenario where China is sending people to Uighur-style re-education camps. It doesn't seem to weigh on people's everyday decision making as much as the threat of being personally identified.

The Hong Kong court system offers some protection here, too—China can’t just hand over mass cell tower records and have that be admissible in court; there would have to be some kind of parallel construciton.

That said, the Hong Kong police can obtain ample surveillance data without a warrant, and the lack of fear of mass surveillance may be more psychological, tying in to the absence of mass arrests. People are afraid of being individually outed, not that authorities will retrospectively identify hundreds of thousands of protesters at some future time.

So people concentrate on the threat they can defeat; they use umbrellas and masks to hide their face at events, some will use a one-time MTR card instead of the Octopus card tied to their identity (since the police can scan a card to see the journeys made).

Nearly everyone carries a working cell phone to protests; few of those phones are burners.

Technology Use

It’s important to stress that Hong Kong protesters are young people improvising under stressful conditions. They are not ubernerds as they have been portrayed in some Western media accounts, but brave, scared, stressed out ordinary people in the hundreds of thousands who are defying China. Painting them as uniquely competent does them a disservice and discounts their very real courage.

Because leaders proved a vulnerable point in 2014, the protesters in 2019 have adopted a decentralized approach to organizing. There is no formal leadership, and the whole thing is held together by social media and personal ties. The result is a kind of “twitch plays protest” process of decision-making (or for those of you too old to get that, you can think of it as leadership by Ouiji board).

The protesters make heavy use of two software tools: LIHKG (Li-dan), a Reddit-like message board, and the messaging app Telegram.

LIHKG

LIHKG is a place for surfacing ideas and discussion. There are two categories of users, indicated visually, based on whether they joined the site before or after a cutoff date at the start of the protests. The site requires a Hong Kong ISP email to join. Both measures are in place to cut down on trolling.The site is administered and run anonymously.

Discussion takes place in Cantonese, and on at least one occasion users adopted a form of written Cantonese that is impenetrable to Mandarin speakers, as a defense against online trolling. Efforts at trolling are somewhat impeded by mainland chauvinism that sees Cantonese as a dialect. This chauvinism has impeded China from taking otherwise obvious steps like mobilizing a pro-mainland Cantonese-speaking community to influence or derail discussions on this public forum.

On August 31, LIHKG was subjected to DDOS attack, taking the site offline. The site moved behind Cloudflare and has since remained up.

Telegram

Telegram is the preferred messenger app among protesters. It’s used for one-on-one messaging between people, among small groups of people to coordinate, and among very large groups to amplify and disseminate information. The polls feature in Telegram is also a way of affirming consensus in group decision making.Several features of Telegram make it attractive to protesters.

- Disappearing messages. If the police force you to unlock your phone, you don’t give up your friends.

- Groups with very large membership (tens of thousands, or even a hundred thousand members). This allows for quick, rapid amplification of news

- Built-in polls. Since the protest is decentralized, some mechanism is needed for decisionmaking. Polls in practice are used to ratify decisions where a consensus has become clear.

- Ease of use.

In late August, it was revealed that Telegram users could be identified as belonging to a group by a dictionary attack.

Telegram responded with a feature that lets users cloak their phone numbers. This does not appear to have affected people's use of Telegram, which supports the thesis that Hong Kongers are less preoccupied with the threat of mass exposure than individual targeting.

Example - Hong Kong Way

An example may help to show the way these technologies are used in practice.

On August 19, someone posted to the LIHKG forum with the idea of forming a human chain in Hong Kong on the 30th anniversary of the Baltic Way protest in the former Soviet Union. Very soon thereafter organizing groups appeared on Telegram. They came up with a map and logistics for how many people would need to be where.

Soon, Telegram groups had formed for each segment of the route, which would shadow the MTR subway system.

The day of the protests, volunteers updated real-time maps and polls showing where people were heading, and which MTR stations needed more attendees. Volunteers at the subway exits helped with staging, ensuring that when the protest started at 8 PM, everyone was already in position and there were no gaps.

A Telegram group organized the final action of the night, having each protester cover their eye and chant “give back the eye” at 9 PM (a reference to a protester who had been blinded in one eye by a police bean bag round).

This large action, which would be impressive in any organizing context, was organized in four days by volunteers who were all strangers to one another. Images of the protest were then used in fan artwork, posters and publicity materials also shared via LIHKG and Telegram.

HKmap.live

HKmap.live is a real-time, volunteer-run live map of protests, including markers for police presence, elite police units, tear gas, demonstrations, and warnings about police in public transit. Information on the map is crowdsourced through Telegram. It came online in early August.Other Services

Hong Kong protesters understand that Twitter has a disproportionate impact on press coverage, and that many Western journalists use the site. Over the last few weeks, there has been an effort to increase Hong Kong’s twitter presence, but reports are that people are finding it hard to acculturate to the site.

Some Hong Kongers use WhatsApp for messaging, but the cap on group sizes makes it less appealing than Telegram. The relative preference for Telegram may also tie in to distrust of Facebook, given its deceitful record around user privacy.

Facebook has a financial relationship with Xinhua, the Chinese state news agency. Xinhua referred to the protesters as cockroaches in an infamous Facebook post (since deleted).

While Twitter blocked Xinhua from buying ads, Facebook and YouTube continue to sell ads to Xinhua even while boasting that they are de-ranking this kind of content in their algorithm. In pracitce, this means Facebook and YouTube are demoting free Xinhua content to make room for paid Xinhua content.

This ongoning relationship does little to build enthusiasm for Facebook or WhatsApp among Hong Kongers.

People to follow

As the protests continue, there are some excellent journalists and observers tweeting in English from Hong Kong. Mary Hui and Xinqi Su livetweet many of the important events in the city. @comparativist is an American social scientist settled in Hong Kong. Kong Tsung-gan is an essayist and writer. Anthony Dapiran is an Australian journalist and the author of a history of dissent in Hong Kong. Lokman Tsui is a professor of journalism and has a special focus on cybersecurity. Mike Bird is a financial journalist who gets caught in the occasional coud of tear gas. Krzysztof Pawliszak is a Polish translator and astute observer of events in Hong Kong who tweets some important events in English. The @BeWaterHK account is the English language twitter voice of an anonymous group of Hong Kong protesters. And the South China Morning Post is the official-ish voice of the Hong Kong government, while also featuring some excellent reporting.

These voices from Hong Kong are a good gateway to many others, both in the territory and in the broader diaspora, reporting on events in real time on Twitter.

—Maciej Ceglowski, 2019

< back to talks