| « Ruling Antarctica | Land of Fire » |

The Collapse of the Perito Moreno

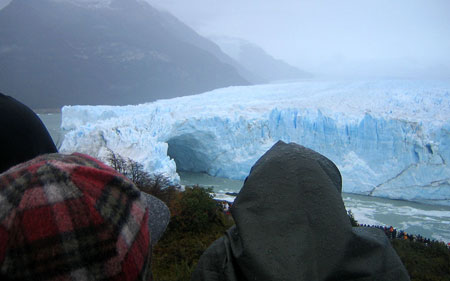

It was pandemonium this month at the Perito Moreno glacier. The Perito Moreno is a giant mess of ice that flows out of the mountains in the southern Argentine province of Santa Cruz, near El Calafate, looking for trouble. In a world of sissy nature that requires protection, handholding, wilderness reserves, careful study and constant medical attention, the Perito Moreno glacier is a refreshing throwback. This glacier wants you dead. It wants to come out and crush you under billions of tons of ice, carve its name into your face, and maraud out into the plains of Patagonia until it reaches the sea. You don't have to go into the mountains looking for the Perito Moreno - it's coming out of the mountains to look for you. It wants to come over there and mess you up good.

Twelve times in the last century, the glacier has tried to take the fight to the Man by crossing the narrow strait that separates it from a series of wooden viewing platforms set up on a mountainside across the lake. And each time, after making it across, the glacier has had its bottom swept out from under it by rising water from the part of the lake dammed by the glacier's advance. This process, "La Ruptura", is spectacular but unpredictable. In some years, the collapse of the weaker bottom of the ice dam leaves behind a natural arch of ice above, which sheds pieces of itself for a few days until collapsing in a glorious Wagnerian finale. This had last happened in 2004, and in early March the waters had broken through the bottom of the dam, creating an ice arch again. A nation whose top news story had involved disputes about an Uruguayan paper mill suddenly found itself watching archival footage of very big ice chunks exploding into water. Anyone who could got in a car and drove straight down to Parque Nacional Los Glaciares.

You may be shocked to learn that Argentines take a rather nationalistic pride in their glaciers. The Perito Moreno is certainly the proudest achievement of Argentine glaciology; they call it the eight wonder of the world here. Authorities will tell you that the Moreno is the only advancing glacier in South America, but this is not actually true: the Perito Moreno has spent most of the past century in a state of dynamic equilibrium, losing two meters of face a day and advancing just far enough to stay in place, with the occasional foray across the lake. A much more remote glacier on the Chilean side, meanwhile, the Pio XI, has turned in in a respectable two thousand meter advance over the last century. But Argentine maps of the Patagonian Ice Field treat Chile a lot like the MTA subway map treats New Jersey - by pretending it doesn't exist - and it is true that the Perito Moreno is unusual in holding its ground. It has scores to settle. It really, really wants to cross that lake.

From a distance, the Perito Moreno looks like a handsome, valley-sized meringue dusted with cocoa powder (crumbled rock). Up close, the ice looks uncannily like bluish marble, with veins of sediment running through it. The front face of the glacier has the crumbly texture of a highly magnified piece of fudge, except that each little flake and bump the size of a large house. There is a radioactive, chemical blue color to much of the ice that I had only seen before in popsicles and bottles of Windex, and had always assumed was an artifact of glacier photography (someone unscrupulous and on deadline in the National Geographic photo lab), but this turns out to be very real. Tiny air bubbles trapped in the ice scatter light and make shadowy parts of the glacier deep blue. Some of the ice is a sky-blue color all through; other areas are completely white. The ice pours down from the mountains in a long series of parallel stripes; and there is a vantage from where you can see most of the seventeen kilometers of the glacier, sloping down so steeply that the valley looks like it has been tipped forward. The glacier ends abruptly at a sheer blue face, as if cut with a cleaver. This is the part that tries to kill you.

A pair of ships plies the waters in the larger lake by the Perito Moreno, sailing back and forth along the glacier's north face with great views of the ice arch and calving front. Twelve dollars buys an hour-long ride about three hundred meters from the ice face, which seems a little far until a larger section calves off and the waves nearly make you spill your drink, a generous two-dollar glass of Old Smuggler served on fresh glacier ice. One of the many mysteries of glacier ice is how it can make Old Smuggler (a.k.a 'wisky nacional', one of the world's more challenging non-single-malts) actually taste good. The effect, however, is undeniable, particularly when you take the heavy-bottomed glass out on deck to sip while looking at the ice show.

From the water, the ice tunnel looks commodious and permanent, making me wonder for a moment if we might actually sail through it. Then a large section of the roof detaches and falls into the water, obliterating everything in a cloud of spray and noise. Small pieces of ejected ice describe elegant parabolas above the top of the glacier, causing residual booms when they hit the water minutes later. The tunnel is a death trap, but what a way to go.

The boat is a terrific way to see the glacier, but after an hour you are booted off and taken in a bus to the viewing area. This is a modest affair of wooden platforms and walkways in a low forest across from the glacier. It is designed to comfortably accomodate several dozen people at a time; the estimated head count on the day of my visit is over six thousand. No one wants to miss the finale. The platforms aren't sloped forward and there is nothing to stand on, so the only way to see anything to find a spot somewhere at the railing. The scene is everhwhere the same - backs of people's heads, families standing in mud, dogs barking, children crying, endless thermoses of hot water for maté and more and more vans and busses arriving with spectators every minute. You can try to stand in the second row to wait someone out, but no one will move, even after it rains for hours. Someone has inevitably hung up a "LAS MALVINAS SON ARGENTINAS" banner on the side of the hill, but this just seems to provoke the glacier further.

I have seen nothing like this in my life. The only glaciers I had encountered before were retreating (or "retiring", as the lovely translations here put it), and had all of the beauty of a mountain of plowed snow in a supermarket parking lot. Both Glacier National Park in Montana and the Glacier Martial in Ushuaia featured glaciers that looked like patches of dirty snow high up on a mountainside, which is exactly what they were. The Perito Moreno, on the other hand, was an handsome and active piece of ice that made me understand what the fuss was about. It was filled with energy and ambition and had no intention of retiring. It was also clearly getting frustrated with having to dam the same lake over and over again, rather than advancing further down the valley to crush the viewing stands and everyone in them.

The glacier had a marvelous grasp of human psychology. It knew exactly how to manipulate the crowd through intermittent reward. Many minutes would pass without anything happening; then, without warning, a piece ranging in size from a Volkswagen to an apartment building would slough off and fall into the water. The enormous size of the fragments made them appear to be falling in slow motion. A few seconds after one hit, there would be an enormous BOOM like that of a nearby thunderstorm, and tall waves would spread through the rapidly flowing meltwater, sloshing the Old Smuggler against the sides of your glass. Sometimes a chain reaction might take down an entire sector of the glacier's face, sending a cloud of cold mist towards us and causing complete chaos in the water and the viewing stands. "Vamo, vamo!" the crowd would yell, as everyone pressed forward and the wooden viewing platforms creaked ominously. At other times, the glacier would sit quietly for an hour or more, in a test of wills, taunting us.

A glacier forms when more snow falls on it than can melt in a given year. This implies the existence of a point (let us call it point A) where so much snow is falling that it can make up for the spectacular daily losses at the glacier's face (point B). There is also a third point, point C, where it is warm and dry and you can sit at an outdoor table drinking beer in the sun. However, the physics of glacier formation ensure that points A and B are very close together, and point C, if it exists at all, is very far away, most likely in El Calafate, eighty kilometers to the east. The same dip in the mountains that allows the Patagonian ice field to form also lets moist Pacific air through to the Argentine side, where it turns to fog and penetrating drizzle.

In the old days (twenty years or so ago), it was quite difficult to reach the Moreno glacier. The trip involved a long drive over dirt roads from distant places like Rio Gallegos or Punto Arenas. Now, however, there is a brand new airport in El Calafate with multiple daily connections to Buenos Aires, Ushuaia and Chile, so that tourists can fly in directly. It takes a certain amount of marketing deftness to advertise non-stop direct flights to a place whose main draw is its legendary inaccessibility, but Patagonian tourist bureaus are up to the challenge. "Wheelchair-accessible Everest" is my own mental shorthand for this process, and I don't really know what to do about it, nor whether I have any right to find it so dispiriting. Someday soon the roads in Santa Cruz, Chubut and Chilean Patagonia will all be paved, and I'm sure I will enjoy the smooth ride, bu something important will be gone. The people in El Calafaté probably see it all a different way; the glacier and airport have made the place a boom town.

The ice arch collapsed on Monday night, the day after my visit. It happened shortly before eleven o'clock under thick overcast, and no one was able to see it or film the collapse, although the tremendous noise it made could be heard twenty kilometers away. A camera boom been trained on the glacier around the clock, but there was no way, yet, to illuminate something so big in a place so remote.

| « Ruling Antarctica | Land of Fire » |

brevity is for the weak

Greatest Hits

The Alameda-Weehawken Burrito TunnelThe story of America's most awesome infrastructure project.

Argentina on Two Steaks A Day

Eating the happiest cows in the world

Scott and Scurvy

Why did 19th century explorers forget the simple cure for scurvy?

No Evidence of Disease

A cancer story with an unfortunate complication.

Controlled Tango Into Terrain

Trying to learn how to dance in Argentina

Dabblers and Blowhards

Calling out Paul Graham for a silly essay about painting

Attacked By Thugs

Warsaw police hijinks

Dating Without Kundera

Practical alternatives to the Slavic Dave Matthews

A Rocket To Nowhere

A Space Shuttle rant

Best Practices For Time Travelers

The story of John Titor, visitor from the future

100 Years Of Turbulence

The Wright Brothers and the harmful effects of patent law

Every Damn Thing

Your Host

Maciej Cegłowski

maciej @ ceglowski.com

Threat

Please ask permission before reprinting full-text posts or I will crush you.