| « The Siege of Carrie Lam |

In the last days of January, I paid a visit to Iowa to observe the political spectacle leading up to the Iowa caucuses.

For readers who don’t follow American politics, Iowa is the first state to vote in our long nominating contest for the presidency. Because the state has a small population (3 million), because the caucus system rewards candidates with a very committed following, and because there is almost a year between the time candidates declare and the vote is held, it’s one of the few places in U.S. national politics where you can interact with national politicians in a small group setting.

I came to Iowa to gawk, not cheerlead. While I have my favorites, this post is meant to give my impression of the several candidates, how they address their supporters, and what it's like watching Americans try to pick their next leader.

I made an effort to attend multiple events by every candidate, and succeeded except with Yang and Steyer, whom I only saw once.

My first event in Iowa is a Biden town hall outside Mason City. I spy Biden's bus ("Bring back the Soul of America") lurking in a hotel parking lot the night before, and my mind spins with the possibilities. Does Biden sleep inside the bus? Does he take a room at the Country Inn and Suites? Does he know the trick of how to check the headboard for bedbugs with a NYC metro card?

I struggle to imagine this world-historical figure in his pajamas, futzing with a cardboard 'do not disturb' sign, trying to fit his tray of leftover angel hair pomodoro into the mini-fridge. But the bus does not lie. Biden is here.

The next morning, I arrive forty minutes early at the snowy fairground venue where Biden is supposed to have his town hall. The place looks boarded up for the winter. The only sign of life is an opportunistic sushi truck idling by the entrance.

I can see other lost souls wandering between the buildings, trying doors. A group of young people with no coats emerges from one building and makes an abortive attempt to tape up a Biden sign. We converge on them and follow them back inside.

Inside, the pavilion is dazzling. It is full of flags, chairs, and a system of rope lines worthy of a mid-sized airport. As a coinnoisseur of Iowa town halls, I can see that we are at the champagne level of budgeting—professional sound gear, a tented tunnel for the candidate to emerge through, spotlights. No expense has been spared. Young staffers in smart, fitted D.C. clothing zip around like bees, taking cues from a clear plastic earpiece. In the back, cameramen are setting up on a platform, while a passel of reporters sits tweeting in their pen.

“I’m sorry,” a chirpy volunteer says after making us sign in, “The doors don’t open until 9:45, unless you’re media. You'll need to go back and wait in your cars.”

And so the small group of retirees, many of whom have been volunteering for Biden for months, shuffles back into the cold. Iowa people are nice like this. They will knock doors for half a year, come early to your weekday morning event, and then go wait in the car, but I am scandalized.

Half an hour later, at the appointed time, the campaign lets the frozen retirees back in. Additional waves of elegantly dressed staffers appear and arrange us around the dais so that the camera angles won't show any empty seats. Not for the first or last time, the attendees at an Iowa town hall are outnumbered by the press.

You get a sense that Iowa is a step down for Joe. Three years ago he was headlining stadium events with Obama, riding in motorcades, flying in his helicopter. The man could hardly look down without finding a red carpet at his feet. Now he's filling his paper plate with breakfast links at the Country Inn and Suites while he waits for the waffle machine to beep. None of the world leaders he boasts about being pals with have to endure such a humbling process. We save it for those who would be President.

Biden's opening act this morning is Conor Lamb, the young Pennsylvania congressman. Lamb looks a bit like his namesake; he looks at us with big, liquid eyes and says the country has no time for on-the-job training, they need a President who can hit the ground running. When Lamb had his moment of fame in a 2018 special election, Biden was the only national figure he allowed to campaign inside his district. Lamb knew that Joe could come in and win votes where any other Democrat would be a liability. Everybody likes Joe. And here he is, right now, to tell you more!

The first impression of Biden is one of extreme age. With Bernie, it’s different—Bernie has been an old man since he was thirty, the advancing years just kind of accumulate, maybe make the hair a little wilder. But Biden was always a vain man. Seeing him up close now, without the makeup or television tan, is jarring.

Still, his eyes sparkle, his voice carries, he works the small crowd well. The years have got nothing on old Joe, he wants us to understand. He's brimming with vigor, ready to serve, ready to win.

Biden’s stump speech has the emotional arc of a standup routine. He starts quiet, riffing on life lessons from Scranton, gauging the crowd a bit. When he has a sense of his audience, he builds up to his peroration, that we are better than this, that we have always been better than this, that America can do anything it puts its mind to (apart from universal health care), and that, come November, he will beat Trump like a drum.

I try to put a name to the emotions Biden evokes. His memories are all of watching his elders struggle in ways that revealed their bedrock decency. There is no kitchen table in Biden's America that doesn't have good people having a hard conversation around it, mud still on their boots, trying to figure out how to get through the next week. When the doorbell rings, it's their equally stoic neighbors, come to help without asking. They come because it is the right thing to do; they would never consider accepting thanks.

There’s an unapologetic kitschiness to this America, Dorothea Lange by way of Norman Rockwell. Biden gets made fun of for it by journalists, but his supporters like the kitsch—an old and effective Nixon trick. “Folks, look” is his most common verbal tic, assuring us that he's speaking from the heart, that he's just gone off script to address us directly, even when the sincere admission is repeated verbatim across a dozen town halls.

Biden has always been notorious for verbal lapses, and now that he's old enough to be accused of senility, he takes more care to get his facts right. But he's not going to be a nerd about it. He has an endearing way of cutting off detailed answers on policy with “anyway…”. You didn't come to hear the facts, after all, you came to hear assurance that Uncle Joe's going to make things right. If you wanted policy, you'd be at a Warren event.

When it works, Biden's cut-to-the-chase moralizing is uplifiting. He calls out Trump at the end of his speech, saying that we want TRUTH instead of LIES, and the crowd cheers. He eviscerates the president for standing next to Putin and betraying his country in full view of the entire world, and the audience roars its approval—it’s everything we want to hear from a Trumpslayer.

But the moral broadsides are less effective when they ricochet off of Biden's Senate record. There's a bit of theatrical business at some of his events when Biden takes a black-bordered card out of his wallet. Every morning, he explains, he updates this card with the exact number of soldiers (“fallen angels!") who have died or been wounded in Iraq and Afghanistan since those wars began. He reads the exact number. And then he bellows at Trump for estimating, for not knowing the exact figure.

At a moment like that, it's hard not to yell "Joe, you voted for the war!" It's even harder to stay quiet when Biden boasts about keeping Bork off the Supreme Court. Does he think we can forget what he did to Anita Hill?

That’s the psychic tug of war at the Biden rallies. Are we signing up for the Joe we want, or the Joe we have? At this late stage in his life, Biden has to reach awfully deep into the well of his childhood memories to get to those formative life lessons, past many strata of Senate votes where the lessons seem to have had little effect.

Biden’s at his best answering questions. He likes to fill the answers with figures and statistics, even when he cuts himself off mid-answer, to show that his mind is sharp. Sometimes his stutter catches him, and he can divert those moments into a moving meditation on the broader theme of empathy, a quality he considers essential to leadership.

More often than not, he will talk about his life’s great tragedy, losing his wife and baby daughter in a 1972 car crash. At the two larger town halls I attend near Cedar Rapids, that story is delegated to the capable Abby Finkenauer, the freshman congresswoman from Iowa’s first district. She tells it movingly, her voice breaking at the same moment in the story both times.

By now, Biden must have shared this story, or heard it told in his presence, thousands of times. I cannot imagine it; the hardest moment in your life turned into a centerpiece of your political campaign. The obligation to bare your soul to an audience of strangers is the most inhuman demand we put on politicians. You are required to produce your authentic self, on demand, while gauging that performance for effect with the dispassionate eye of a stage actor.

But Biden takes this to unusual lengths. He seems to need these raw moments in order to forge a connection with his audience. The stories get embellished, they lose their connection with reality. For a time, the story of his wife's and daughter's deaths included a fictitious drunk driver, a detail that has been removed in 2020. His need for a raw, emotional hook in even the smallest setting is remarkable. We all make fun of the "no malarkey" slogan, but it is a succinct and honest statement of the Biden credo. The man needs to bare his soul, he needs to connect.

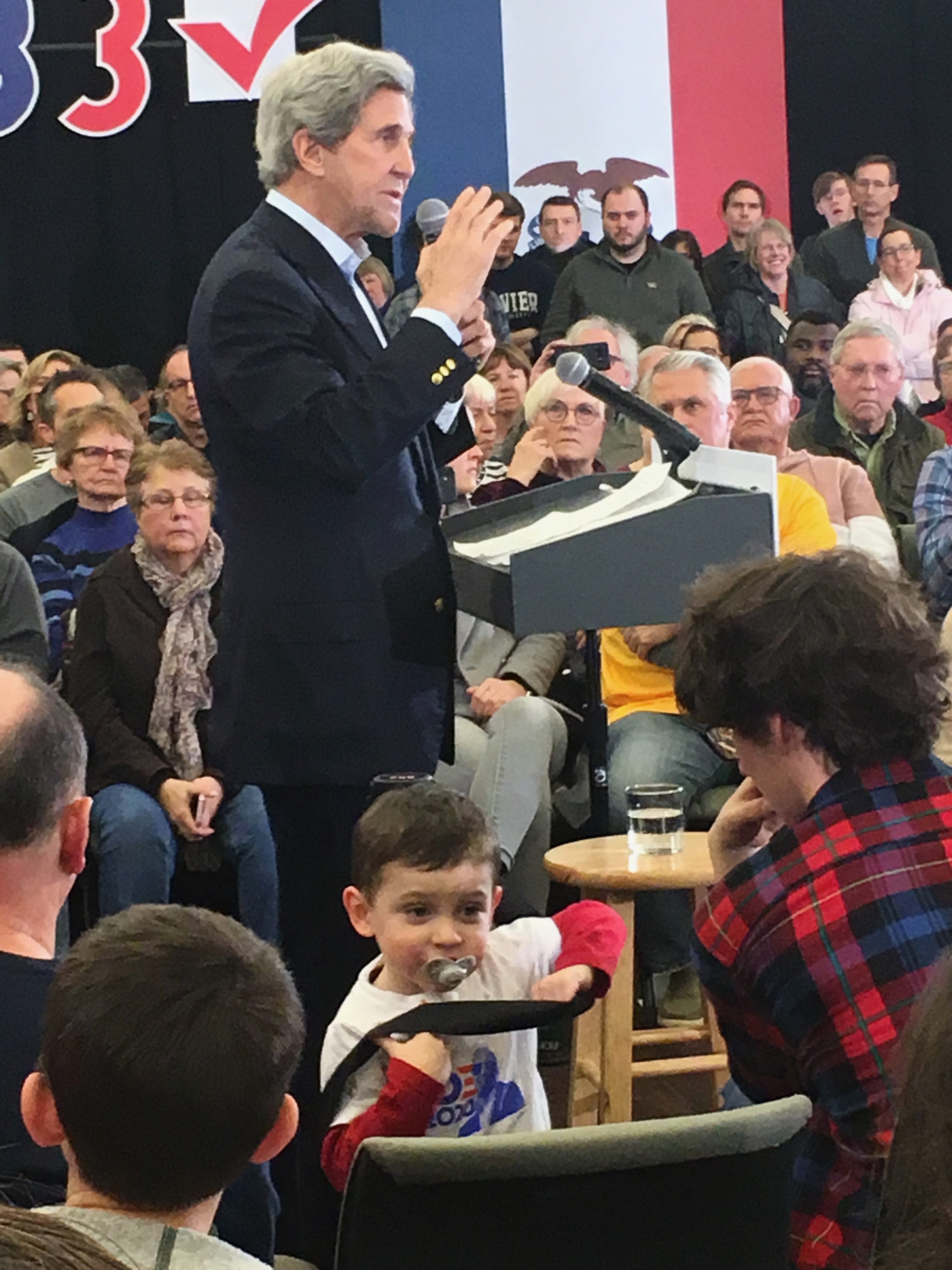

The best reason to go see Biden is to watch him interact with children. He latches on with total intensity, just this side of creepy, and will do whatever it takes to win their affection. At the end of Biden's event in Cedar Rapids, John Kerry is giving a closing speech when the candidate spies a toddler across him on the stage platform. Kerry, looking like a weary tortoise who has been removed from his shell, is talking about high-capacity magazines, working his way to up to a low-energy denunciation of the gun lobby.

A grinning Biden sits behind him, twirling a golden medallion to catch the light. The toddler notices; the toddler stares. There is tittering in the crowd. Poor Kerry, stranded far out on a moral promontory, does his best to steer his speech through the waves of inexplicable laughter. We need common sense gun laws! We need an end to school massacres! Meanwhile, the kid stumbles across the stage, falls, gets up, grabs the medal. Biden teases, won't let go, then relents. There is a great release of tension, laughter and applause. Biden's white grin shines as bright as the medallion. Poor Kerry moves on to abortion.

What must go through Kerry’s mind? He fidgets all through Biden’s speechmaking, foot racing back and forth, this former diplomat who has sat through far duller meetings in his time. Quite a torture this must be for the ambitious! Kerry ran in Iowa 16 years ago, and is still younger than the man he has come to endorse. What must Al Gore, or Howard Dean, or Hillary Clinton be thinking, politicians who were told that their elect-by date was long past, only to see Diamond Joe pass them on his way up the ladder? Any one of them, if they entered this race now, would be the fourth-oldest candidate in a wide-open contest.

Kerry reminds the crowd at the end of his remarks that Nancy Pelosi is 79. “Isn’t she doing a great job?" he creaks, and the crowd claps uneasily. "Aren't you happy she's in charge? That’s because seventy is the new forty!”

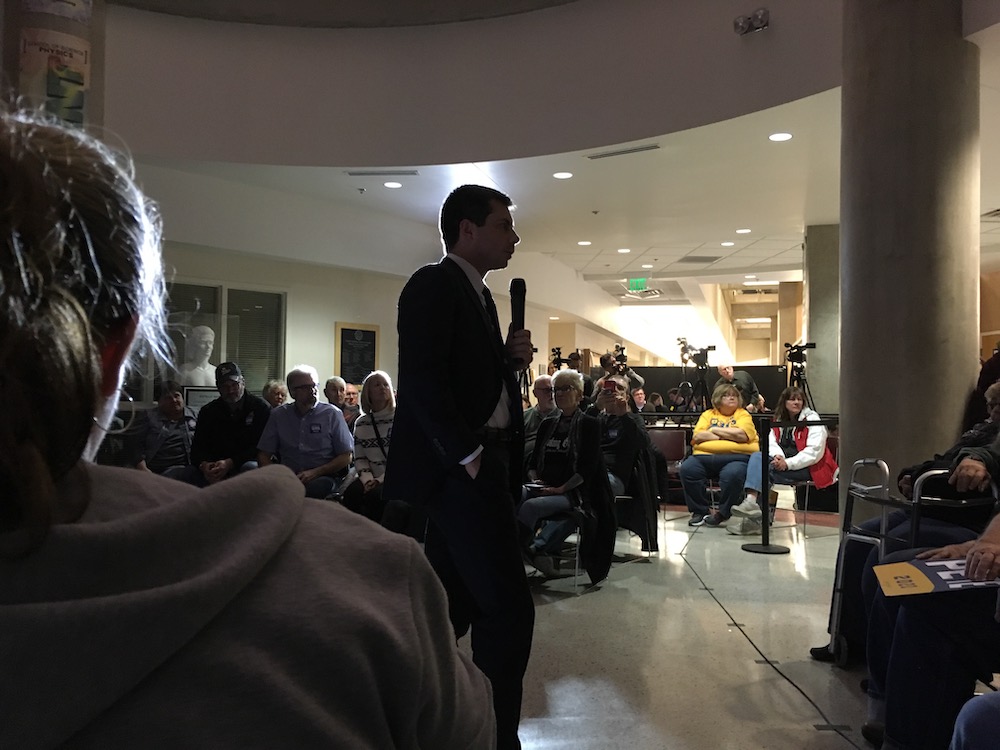

Pete Buttigieg

For those who don't know him, Pete Buttigieg is the thirty-eight year old mayor of South Bend, Indiana, population 102,245, who has improbably become a serious presidential contender, the way a flightless bird can become the dominant animal on a remote island that has not yet been visited by snakes or rats.

And Mayor Pete’s events are packed! He fills hotel ballrooms to capacity even in small towns like Carroll. Pete is no Bernie—the Vermont senator gets ten times the attendance of any other candidate—but going down a string of small towns in western Iowa and getting overflow attendance is not a small political accomplishment. Buttigieg’s and Warren's campaigns have the reputation of being the most thoroughly organized in Iowa, but it's Buttigieg who shows up more—Warren has only held three events much west of Des Moines.

There are some candidates who give you a strong sense of themselves as people when you meet them. I don’t mean that they are somehow authentic, whatever that loaded word means in politics. I mean that when you see them, you get a glimpse of the human being who lives under the mask.

Buttigieg is not one of those people. The mayor has clearly been studying the 2008 Obama game tapes, and the person who walks out is a younger, slighter, whiter version of candidate Obama from that year. He has the same message of hope and unity, his sentences roll in the same cadences, the build in the familiar crescendo, you are almost surprised not to hear about his childhood in Indonesia and Kenyan father.

Accusing Buttigieg of being a political chameleon is not completely fair; he is a boyish-looking 38 and could never afford the moments of levity or bathos of someone like Biden (who was ten years in the Senate the day Buttigieg was born). Buttigieg must be presidential in every moment, or the illusion will burst. But it’s weird to see the act in person, the self control, the rhetorical precision, and just how thoroughly Progressive Pete of the early primaries has been reupholstered into a heartland centrist.

The theme of Pete’s events is that Americans are united, but Congress divides us. He is a small-town Midwestern mayor who, just like the rest of you folks, has suffered at the hands of the bureaucrats and ideologues in D.C. who don’t understand what it's like to live in the real America. On issue after issue, the rancor in Washington does not match the general consensus of the good people in the heartland, whether we’re talking about health care, gun control, or immigration.

Curiously, is the same argument that Bernie Sanders makes, though Bernie frames it as a Manichaen conflict between billionaires and an oppressed but astonishingly politically correct working class. Both men, however, propose the same remedy. To use Buttigieg’s words, he will “fly that big blue plane into a town of obstructonist congressmen” and take the case directly to the people.

Like a lot of things Buttigieg, the imagery works uness you start to dwell on it. The idea of President Pete flying in to rural Kentucky to warn Mitch McConnell that there’s a new sherriff in town, and that he better change his obstructin’ ways or face electoral doom in 2026, is preposterous. Even Roosevelt, who tried this approach at the height of his popularity, ended up humiliated.

But the audience likes the line. The audience likes every line! Mayor Pete is a pez dispenser for political affirmations, and any phrases that fail to soar get quietly taken out back and are never heard from again.

Pete knows what this crowd longs to hear most—that we seek unity, that a new day will dawn after Trump, that electing this young mayor will end our national nightmare and things will be decent again. “I’m a candidate that will make your blood pressure go down, not up” he promises in one of his most reliable applause lines, echoing Michael Bennet's less famous (and far too successful) promise to disappear “for weeks at a time” if elected President.

Bennet's self-effacement worked too well—the invisible purple-staet senator dropped out after winning 963 votes in New Hampshire. But Pete has built a successful candidacy on a substantially similar promise. The mayor promises he will be electoral Xanax, tapping into America's desire to be profoundly sedated.

Of course, there is policy, too, for those who want it. He wants a national service program with a “climate corps”. He’s studied his Iowa briefing sheet and talks about cover crops and soil management. His medical plan is the magnificently squirrely “Medicare for all who want it”, the second half of the phrase an asterisk for the first.

But again, if you wanted policy, you’d go see Warren. You are at a Pete event because you want to see if you can bring yourself to see this young, untested man as President.

Mayor Pete is forever skating on the edge of the ridiculous. Like a kid trying to buy liquor with a fake ID, he knows that the only way to sell this performance to skeptical eyse is to brazen it out. And he carries it!

Asked about gun massacres, the former naval intelligence desk officer recalls his military training, recalling the vow he made as he chambered rounds into his weapon that no teacher should ever be called on to confront these hideous tools of destruction.

Asked about his electoral inexperience, he explains with total sincerity that a mayor, unlike a Senator, must manage a staff of hundreds, and is therefore better prepared for the demands of the Executive Branch than someone who has spent their career moving major legislation through Congress.

When a questioner introduces herself as a schoolteacher, he interrupts her to say “thank you for your service”, and there is a delicious pause as we all try to process whether he’s kidding, whether this most unctuous of candidates has dared to make a subversive joke. But he has not, he is in earnest. There is no room for sarcasm or subversion in Pete Buttigieg’s America.

But like I said, he carries it! He passes as presidential, and the crowds who come to see him applaud him and go home reassured that maybe they don’t have to vote for Biden after all.

Watching Mayor Pete is like being stuck in one of the later Matrix movies. It’s a restless two hours that that causes one to think weird Baudrillard thoughts about simulacra and the nature of reality. What does it mean to play a role for so long and with such fidelity that you become it? Does authenticity, the fact of not having experienced any real loss in a life defined by upward striving, matter at all in the public theater of politics?

There’s also something protean about the mayor, a sense that we have not seen this shapeshifter's final form. Life has never sunk its claws very deep into Mayor Pete, and told us who he is at bottom. Do we want to give him the presidency to help him find himself, or is it okay to wait a few elections? Buttigieg could take 40 years off, run again, and still be younger than Bernie is now. There is no hurry.

Yet you have to respect the hustle. That’s a deeper subtext of the Buttigieg campaign: maybe I'll be a fake President, but look how hard I can work at it. And in 2020, that is an appealing argument. Maybe we want the guy conning us to put just his back into it a little.

Tom Steyer

It is a joy to attend an event by Tom Steyer, because you know you are costing him money. Like a failed athlete who hires a stadium of cheering fans to watch him lumber around the track, Steyer has paid a fortune for the trappings of a top-tier presidential campaign, complete with tour bus, field organizers, and expert advisers who assure him his chances are excellent while demanding to be paid in advance.

At a morning town hall in Baggio’s Italian Restaurant in Knoxville, five cameras stand on a dais ready to capture the man Steyer talking to the people, and you have to wonder, is this actual media? Would any sane reporter make it their job to follow this man around? Or did the hedge fund billionaire buy himself a newspaper and TV station to cover his town halls, too?

Every candidate in Iowa talks about revitalizing the small town economy, but Steyer has been doing it, running his preposterous vanity campaign from town to town to the joy of bakeries, diners, hotels and gas stations around the state. He keeps field offices running that will never see a volunteer and stocks them with high-thread-count hoodies free for the asking. His donuts are the finest donuts you can get in central Iowa (I fill my pockets). He dominates YouTube so completely with ads that little Iowa children cry in frustration to their parents.

Steyer’s manifestly sincere desire to help gives his egomania extra savor. Like a giant dog tracking mud through the house, breaking crockery with his wagging tail, he can’t understand why his favorite people are all so mad at him. You can see it in his eyes on TV when he tries to chat up Bernie after a debate, and hear it in his rather plaintive opening remarks at his town hall now.

"I've been a community organizer for the past seven years", Steyer begins, “I know that people describe me as being a rich person, but that’s not how I think of myself.” His uncle was a law professor, he explains, his grandfather was a plumber. He understands what it means to be a farmer, because “I raise grass-finished cattle and chickens in California. Our family has done that for 15-20 years. I know how tough the rural economy is."

He's not doing this for his resumé, Steyer insists. He has come to Iowa to "save rural people, the underserved, and the whole planet." Sure, impeachment is happening now, but he was funding impeachment a year before anyone else was even talking about it. “I’m a grassroots guy!” the largest individual donor in American politics pleads more than once into the microphone. “This is a grassroots movement!”

The audience is friendly to Steyer. They appreciate his focus on climate change, and the first questioner delicately asks what position he would be willing to accept in… well, in a real administration. But Steyer is adamant that he is going for the win. He lays out his curious theory of Trump, that the President’s supporters all despise him but think that he’s good for the economy.

In Steyer's mind, Trump is personally unpopular, but offer his voters a devil's bargain. "You would never invite me in the door in Knoxville Iowa and invite me for dinner," he imagines Trump saying, "But you’re going to vote for me because the Democrats are a bunch of socialists."

I wonder if Steyer has ever had a sincere talk with Trump voters, of whom there is no shortage even here in Knoxville. Iowa swung to the right harder than almost any state in the country in 2016. The president is a divisive figure, but he is also broadly and genuinely popular. He would be a welcome dinner guest across Iowa, perhaps in more places than the hedge fund billionaire.

But to Steyer, Trump is a sham, and I wonder if there is a little bit of projection going on here. This ersatz politician insists that only he can get on the debate stage and expose the President for not being a genuine businessman, and that this great unmasking will destroy Trump's chances of re-election.

Steyer, of course, is also not who he claims to be. He's a political space tourist, the equivalent of those billionaires who bought themselves a flight to the rickety Mir space station and were given some face-saving experiments to do, to pretend that they weren't just joy riding. It is Steyer's misfortune now to run in the shadow of Mike Bloomberg. Even as a billionaire trying to buy an American presidential election, the poor guy can't stand out.

Leaving the restaurant, we are forced to walk through a cloud of Tom Steyer's bus exhaust, as the climate candidate has parked his idling campaign bus directly in front of the doorway. He just makes it too easy. Challenge us, Tom! Make us work for it a little. Maybe then we will respect you more!

Elizabeth Warren

There’s an old joke about Adlai Stevenson, the cerebral governor who ran against Eisenhower in the 1952 election. After hearing one of his speeches, an enraptured supporter runs up to offer his congratulatons.

“Governor, every thinking person in America will be voting for you come November!”

Stevenson replies, “I’m afraid that won’t do—I need a majority.”

I think about this dumb joke every time I find myself in a room of fired up schoolteachers and librarians (I say this as the highest form of praise) at an Elizabeth Warren rally. Warren is the thinking person's candidate, in a country that elected Donald Trump.

Put in less sympathetic terms, she is the candidate of a certain American elite, the group of educated professionals, academics, and journalists who in Polish politics we refer to as "the salon". These are right-thinking people, enlightened people, but also self-righteous and somewhat grating people who are easy fodder for the politics of resentment.

If Bernie’s rallies feel like everyone just got off the Greyhound bus from Portland, Warren brings out the organic co-op militant, an NPR fund drive that has decided it will not longer accept no for an answer. There is a preponderance of women at Warren's events, and a surprising number of teenagers and middle school kids, some brought out by their parents, others dragging their parents with them. It is a crowd of people who love books and learning, which fills me with dread.

I recognize these people—these are my people—and America does not like us much.

There is a feeling, unique to Warren's campaign, that makes it almost like a club. Everyone knows about Bailey, the family dog, who takes photos in the candidate’s stead when her schedule is too closely packed to allow her to linger. Everyone also knows Warren’s husband, a sort of decaffeinated version of Mr. Rogers—they all just call him Bruce. Warren is famous among her supporters for her willingness to stay and pose for an unending series of selfies, with anyone who wants them, and unless the schedule precludes it she is true to her word (what does it mean that the two women running, Warren and Klobuchar, are the ones who stay for hours to take every photo?)

At my first Warren event, in Des Moines, it's not clear that we’ll even get to see the Senator. A procedural vote on impeachment has kept all the senator candidates stuck in D.C. until late in the afternoon. Bernie Sanders decides to phone in to his massive Des Moines rally (featuring Bon Iver!), but Warren, always willing to outwork Bernie, has boarded a plane and is on her way. While we wait to hear from her, her three co-chairs, Congresswomen Katie Porter, Deb Haaland, and Ayanna Pressley, come up to the podium to speak on her behalf.

The great progressive split in 2020 is about tactics, not policy. Should the emboldened left take over the Democratic Party from the outside, like Bernie, or from within? Katie Porter is the Platonic ideal of the second strategy, her career almost a pastiche of Warren's, a populist-speaking law professor whose district become just educated and affluent enough in 2018 to elect her over a villainous Republican incumbent.

Porter tells the crowd what they want to hear—that America is hungry for more of these smart progressive women to win, that they're tired of Trump and his mendacity, they want someone bold and competent to come in with a plan, and Elzabeth Warren (here the crowd is ready to chant along) has a plan for that.

The recurring theme from every opening speaker is that Warren listens. Her supporters will tell you this in an almost cult-like way; the senator listens! She hears you! She will take questions for hours, answer you in paragraphs of filigreed, finished policy. She will show her work on the blackboard.

Warren’s personal story is incredible, growing up in Oklahoma with three much older brothers, fired for being pregnant, but somehow pulling herself up ever rung of the ladder all the way up to a teaching position at Harvard, where she distinguished herself as a law professor. As the motive force behind the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, she became a rare hero in a financial crisis where big finance completed its capture of the Democratic Party. And then, after Obama failed to appoint her to the head of that body, she was an early martyr to the President's fatal love affair with Wall Street.

Ayanna Pressley, the last woman to speak on Warren’s behalf, is probably the best orator to come through in Iowa in 2020. “Policy is my love language,” she explains to a cheering crowd, after having worked us up into a frenzy of optimism, feeling like we can do anything, burst out of those doors, take over the world.

Poor Bruce, the husband, has to try to follow her. He apologizes to the crowd for not being his wife, explains that the impeachment proceedings have thrown off the schedule, and invites people to cross the street to a brew pub, where the Senator will arrive sometime before midnight.

The brew pub does a brisk trade that night. Like they do everywhere, the press claims the central space for themselves. Warren supporters have to fight it out (in the passive-aggressive way of the highly educated) to claim a spot in the margins. The candidate herself arrives well towards midnight, offers a brief speech of thanks and then stands in front of a wall of beer barrels, working her way through a line of people who want to take selfies. She's dressed in sneakers and a zip-up campaign hoodie, the informal clothes themselves a statement. This is a campaign about substance, not surface!

Warren's campaign, along with Buttigieg's, has the reputation of being the best-organized in Iowa. But while Biden tours the state like he is under duress, and Bernie's team can't seem to master basic political skills, like reaching out to local mayors to let them know they're coming, Warren's many field offices form an archipelago of sunny competence. Each is staffed with optimistic youth from out of state, working calmly according to—what else—a master plan.

And yet, the plan never seems to involve putting Warren in front of the kinds of struggling rural voters she claims she can reach. While Buttigieg and Klobuchar show up in the smallest towns, Warren stays in the blue parts of the state. She will only hold three events west of the Des Moines area in a whole season of campaigning.

The second time I see Warren is at a daytime rally in a large gymnasium at Coe College, where a succession of women, building up from student leader through local state reps, once again tell us that Warren is the candidate who listens. I like the implicit contrast with Bernie on this point. The idea of Bernie listening is almost sacrilegious—the whole point of Bernie is that he has already heard it all, he does not need to listen, because he was there years ago already fighting for whatever problem it is that you have.

But if Bernie is the shouty old man, Warren is the tough but fair professor you can also open your heart to. The point is never made so explicitly, but it's there for the taking. And this stylistic contrast with her great rival (along with the sexism that is Warren's constant headwind) is probably the most gendered thing about the Warren campaign.

When Warren comes up to speak, after another stemwinder by Pressley, she is all eagerness to move to questions, eager to talk specifics. Hers isn't a sentimental stump speech about 'the soul of America', or bringing morality and sanity back to the White House, but an insistence that the American voter will settle for nothing less than "comprehensive structural reform". This honey in my ears. I swoon. I am a structuralist; I want a candidate who will promise to crawl under the hood of American empire and bash at it with a large wrench until all the rusty parts fall out.

But I also remember the Buttigieg rallies, the waves of applause at even the fuzziest bromides. People at those rallies wanted to feel good, wanted to believe in the antithesis of Warren's message—that everything would just work itself out in the fullness of time, and we shouldn't worry so much.

Warren has a tremulous voice that sometimes makes it sounds like she’s at a high pitch of emotion when she is not. It serves her best when she's going deep into policy, speaking with precision while sounding like an avenging angel come to smite the corporate class with brimstone.

There is a policy for everything. You have the impression that a vault full of legislation waits stacked in binders for the Hundred Days to begin. A question about how to overcome partisan gridlock turns into a seminar on hearing aids—have you ever wondered why they are ten times more expensive than a smartphone? The answer is monopoly power, and Warren was able to pass a bill with Republican support to open that market to new entrants.

The crowd has never thought about hearing aids before, but they are enchanted. Once again they discover that Warren was working under the radar to pass laws they didn't even know America needed. There is the sense there are whole reams of policy Warren is dying to be asked about on stage, so she can go into it in similar detail. Warren's handlers try to hurry her along—it is the weekend before the caucus, a day packed with appearances—but she will not go, she must take one more question.

It’s irresistible, inspiring, and also leaves me with a leaden feeling in my stomach. American politics is not kind to the visibly intelligent, let alone smart women. Like so much in this election year, the question of whether Warren can be nominated leaves me wondering—can we ever have nice things? Is America ready to elect a former schoolteacher over the class bully? And could Bernie voters, who back a nearly identical platform that they insist is a revolution, ever forgive Warren for not being Bernie?

My last glimpse of Warren comes not in Iowa, but two weeks later in New Hampshire, when she has just been defeated in the primary. As thousands of distraught volunteers mope around her, Warren stands on a platform in the middle of an airplane hangar, still shaking hands, grinning, side-hugging her way through a rope line of people seeking comfort. She does it for the better part of two hours, on the most bitter night of her campaign, indefatigable, resilient.

| « The Siege of Carrie Lam |

brevity is for the weak

Greatest Hits

The Alameda-Weehawken Burrito TunnelThe story of America's most awesome infrastructure project.

Argentina on Two Steaks A Day

Eating the happiest cows in the world

Scott and Scurvy

Why did 19th century explorers forget the simple cure for scurvy?

No Evidence of Disease

A cancer story with an unfortunate complication.

Controlled Tango Into Terrain

Trying to learn how to dance in Argentina

Dabblers and Blowhards

Calling out Paul Graham for a silly essay about painting

Attacked By Thugs

Warsaw police hijinks

Dating Without Kundera

Practical alternatives to the Slavic Dave Matthews

A Rocket To Nowhere

A Space Shuttle rant

Best Practices For Time Travelers

The story of John Titor, visitor from the future

100 Years Of Turbulence

The Wright Brothers and the harmful effects of patent law

Every Damn Thing

Your Host

Maciej Cegłowski

maciej @ ceglowski.com

Threat

Please ask permission before reprinting full-text posts or I will crush you.