| « No Evidence of Disease | Total Eclipse of the Sun » |

Botoșani! Botoșani! Botoșani!

What poet can sing your praises? Whose arms are thick enough to heft that industrial-strength lyre? Whose inner eye can see past your grit and mud, your packs of ownerless little nippy dogs, your undrainable streets, your unsportingly silent mosquito, and celebrate the glowing, inner you?

I guess it's no coincidence that Botoșani gave us the great bard Eminescu, the Romanian national poet and only man of sufficent tonnage to handle the job. I certainly could never do it. I loved Romanians, loved their country; I even loved Moldavia, but felt like I met my match with Botoșani.

And it was always so damn hard to get out of there.

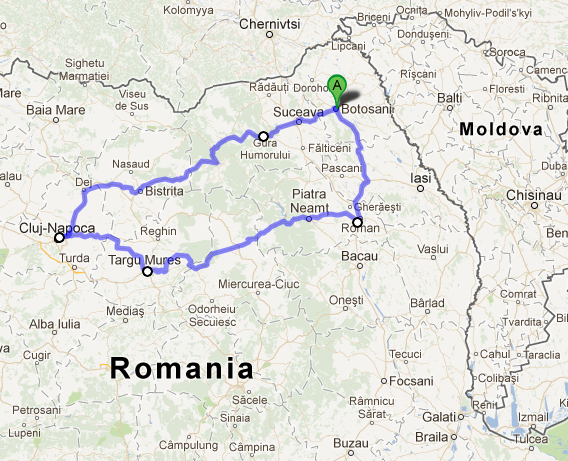

In the spring of 2009, Diane (who was doing a Peace Corps stint in Romania) decided to go on vacation with her American friend. She needed to get to the airport in Cluj-Napoca, to catch a discount flight to Italy. Rather than condemning her to an overnight bus journey or train trip on the local bone-shaker, we decided it might be fun to rent a car and make the drive over the mountains. In the process, we could see a chunk of the country that is ordinarily hard to get to.

The car rental place was (like so many things in Botoșani) an ad-hoc outfit run out of somebody’s back office. The proprietors seemed surprised that someone was actually renting their car, but rallied quickly. We filled out the handwritten rental forms in pentuplicate, participated in the fusillade of stamping that accompanies any official transaction in Romania, and set off on the Friday before Easter in a growly diesel Renault.

Urban catastrophe though it may be, Botoșani is surrounded by lush agricultural land, and it does not take many minutes of driving on a beautiful spring day before you have a song on your lips, and begin to think the great bard Eminescu may have been on to something.

The first part of our drive is the familiar road to Suceava, the city you go to when you want to go somewhere else. We pass the large metal stork statue near the local airport. Spring is far enough along that the real storks have started making their way back to Romania, too. They are big, goofy birds who walk through fields with a quiet dignity, looking for frogs to eat. Whether because they eat pests, or set a good example by mating for life, storks are universally beloved. You can see their big nests on top of some power poles and a lucky roof or two. It's a longstanding superstition that having a pair of storks nest on top of your house brings luck, so many people will set up a platform in hopes of enticing a couple.

Botoșani and Suceava are both in a region called Bucovina famous for its old painted monasteries. To my regret, there's no time to visit them now, though some of the gorgeous wooden churches are visible from the road. I am told there are guesthouses you can stay in along the way, where the table groans under the weight of your breakfast. Romanians are deeply religious, and somehow the wooden Orthodox churches survived the insanity of the Ceaușescu era, and are lovingly tended now.

A BRIEF INTERLUDE ON DRIVING IN THE FORMER EASTERN BLOC

Limited-access highways in the style of the German Autobahn don't really exist in Eastern Europe. Every country has a couple of dozen kilometers of the stuff built for demonstration purposes, in hopes of luring more European Union funding, but apart from these show pieces the road system consists of two-lane roads with lots of roundabouts and no restrictions on traffic. However many legs or wheels your means of transport has, and however low your top speed, you are welcome on the roads of Romania.

Passenger cars must contend with horse-drawn carts, overloaded trucks, cyclists and pedestrians for control of roads that double as the main street of every village they pass through.

Home builders in a Romanian village approach the main road like a basketball player muscling in towards the basket. They try to get in as close as possible, back side first. Houses are never built to face the road, which was traditionally a place of mud, dust, and horse crap. Rather, there is a big windowless wall with a tiny gate leading to the courtyard, where you find the real entryway. From the driver’s perpective, this turns each village into a twisting tunnel of masonry, with pedestrians pinned between the walls like cattle in a chute. Nor has any provision been made for the speed of modern auto traffic. The road whipsaws between buildings at odd angles with no warning, until abruptly you are back out in the fields and everyone is pretending they're on the Autobahn again.

The typical Romanian driver is a man of faith. He sees the road as it is — a densely congested, shattered series of uneven concrete blocks — but does not let the sordid reality obscure the promise of what it could be: a ribbon of silken asphalt winding from horizon to horizon, without another car in sight, if only he could get past the moron in front of him. And, he feels, God will reward those who put their faith in Him, floor it and swing out on a blind curve. Look in any truck or taxi and you will find a little icon of a saint dangling from the rear view mirror. This is basically an admission that the driver does not expect to survive without sustained and direct divine intervention, something that I will find easier to believe after returning home from this road trip.

To pass in an underpowered car on a two-lane road requires pretending that the middle of the road is a kind of third lane. Drivers coming from the other direction will believe the same thing, creating a tendency to turn any straight stretch of road into a game of chicken, as two Dacias with throttles wide open simultaneously pull out from behind their respective poultry trucks into a showdown.

Where the road enters a village or crosses some particularly hilly terrain, passing is just flat-out prohibited and everyone settles into a sulky, single file convoy.

The two-lane passing game is not unique to Romania. But the Romanians have brought it to a higher pitch. Not content to just plant big death trees lining the road like they do in France, the Romanians have added a kind of concrete-lipped slit trench the exact width of a car tire along the edge of the asphalt. I assume that, like blood gutters in a bayonet, these trenches are intended for drainage. The ditches are not always there — sometimes there is just an unpretentious dropoff into an adjacent valley.

These six elements: all-purpose roads, huge variations in speed, constrained shoulders, novice drivers, Balkan ideas of manhood, and mountainous terrain—conspire with the awful state of the pavement to make memories of driving in Romania ones that will last a (possibly very abbreviated) lifetime.

A BRIEF INTERLUDE ON ROMANIAN GEOGRAPHY

Cluj (pronounced ‘kluge’) is an old Transylvanian city in the northwestern part of the country. Botoșani lies in the pancake-flat eastern strip called Moldavia, not far from the Ukrainian and Moldovan borders. To get from Botoșani to Cluj, you have to cross the Carpathian mountains.

Everyone in Romania will tell you the country is shaped like a goldfish. To me, it has always looked more like an overturned jug, with the Black Sea spilling out. The Carpathians come in from the top and cut about halfway down the middle before turning sharply to the west just before Ploiești.

This geological double-take divides the country into several mutually inconvenient regions.

The strip between the mountains and the Moldovan border, where we lived, is a flat, fertile plain identical in every way to the fields of Ukraine, Poland and Moldova.

South and east of the mountains is the Danube delta, a swampy wetland and summer vacation paradise that serves roughly the role of Florida in Romanian life.

Along the north and west of the country are flat bits with historical ties to Serbia and Hungary, of which they form a natural extension.

Squeezed between the mountains and the Bulgarian border is the province of Wallachia, historically the most accessible and easiest to oppress by Turkish neighbors, and home to Bucharest and most of the country's population.

And in the center of Romania, where the mountain range makes its bend, is Transylvania.

To American ears, the name immediately conjures vampires, or at least early childhood lessons about counting things. But the literal meaning of the name is just “beyond the forest”①. In German and Slavic-speaking countries, Transylvania has a more evocative name, Siedmiogród, or Siebenbürgen, that translates to ‘Seven Cities’.

A BRIEF INTERLUDE ON EARLY EUROPEAN MIGRATIONS, OR WHY THERE ARE SEVEN CITIES IN TRANSYLVANIA

A very long time ago, the Eurasian steppe was full of hordes. The hordes had names and histories, but were all basically mounted nomads who had indestructible little horses and were good at shooting people. Sometimes, a horde out in Central Asia would pick a fight with a neighboring horde, and it would start a domino effect from west to east, ending when some disposessed horde finally galloped out into Europe.

Eastern Europe at the time was full of fat settled Franks and beefy Slavs, good at tilling the soil, but no match for the mounted horrors from the steppe. At some point in this process, the nomadic Hungarians arrived from Siberia, and quickly acquired such a taste for European looting that they proved impossible to get rid of, spending the best part of a century sacking the stuffing out of places as remote as Spain and Italy.

At that point, perhaps out of sheer fatigue, the Hungarians decided to settle down.

The place they picked was the Carpathian basin, a flat bowl of land comprising modern-day Hungary, northwest Romania, and parts of Slovakia and Serbia. It was nice, fertile, completely flat ground protected by the Carpathian mountains in the east and the Alps in the West. A good place to graze horses, a nice place to raise a family.

The problem was how to prevent the next group of nomads from coming out of the steppe and out-Hungarianing the Hungarians at their own game. So the Hungarian king undertook to fortify the Carpathian mountain passes, the only useful natural obstacle between him and his old friends out east.

Lacking manpower, he turned to western Germany and Luxembourg, and invited colonists in those overpopulated lands to come to Transylvania and build some castles. This group came to be known as the Transylvanian Saxons (still one of the finest things you can name a sports team). The Hungarians promised the Saxons autonomy and a good cut of the merchant traffic that came through the mountain passes. The Saxons, handy with a mortar and wise to a deal, agreed, and built seven beautiful cities.

So this is why, in the center of modern Romania, there is a province that speaks almost exclusively Hungarian, and in that province lie seven German cities called Kronstadt, Schäßburg, Mediasch, Hermannstadt, Mühlbach, Bistritz and Clausenburg②.

A RETURN TO THE GRIPPING STORY OF A ROAD TRIP TO CLUJ-NAPOCA

The rolling countryside is pretty in the springtime. The only thing that mars the landscape are the telegraph and power poles, which for whatever reason are made of poured concrete rather than wood or metal, and have that instantly dingy look that was only achievable under advanced socialism.

West of Suceava, as we enter the forest, the drive grows hilly and dusk begins to descend. As we enter the high foothills and approach Transylvania, a sinister orange full moon pops up, as if on cue, over a ridgeline. A solitary wolf fails to howl in the distance—he must have the night off.

Our entry into Transylvania does mark the start of a night of terror, but for completely mundane reasons. As I reach the bottom of a gradual downhill curve, the road suddenly turns from smooth concrete into a chaos of loose rubble. Someone has cut a wide trench across the pavement and, satisfied with a job well done, left it unmarked and invisible. For a moment I fear I might lose control of the car.

Further on, just as my pulse is settling, we come across a railroad track. The lights are blinking and the semaphores are down, but they are only about a meter long, barely reaching over the packed earth along the edge of the road. I stop to wonder at this just as a train thunders across our path.

“You have got to be kidding.”

Around ten o'clock, we arrive in Bistrița, the setting of Bram Stoker's Dracula. This is one of those seven German cities, but the name comes from the Slavic phrase for 'fast water'. It's a beautiful, clean town full of trees. I remember being particularly impressed by the freshly-painted, functioning crosswalks, an undreamed-of luxury in our corner of the country. Bistrița is not shy in the pursuit of the vampire tourism dollar. We pass a hotel called the Golden Crown, lifted directly from Stoker's novel, along with several other Dracula landmarks before reaching our hotel.

A very un-vampire-like young man with careful English greets us at the door. We appear to be the only guests in the entire hotel, and briefly I am filled with hope that I'll hear the Toccata and Fugue blaring in some distant attic as he escorts us up the stairs with a dripping candelabra. Instead, he asks us if we have eaten, and when we say we have not, he rouses the hotel staff to make us supper. The meal is delicious but hard to enjoy, given that we seem to have gotten at least four people out of bed to cook. As we eat, our host hovers over a computer console at the other end of the dining room, putting together a playlist for us.

After dinner, he takes us up to our room. In the lobby and on the landing we see some strange cushioned platforms about a meter square, with joystick-like handles at opposite corners; they look like something you might use for physical therapy, or an excessively comfortable torture device. We ask our host about them on our way out of the dining room.

“This week we have been hosting a Skanderbeg tournament,” he explains.

Noting our blank faces, he apologizes for his English and tries again.

“Skanderbeg. Do you know it? For the men with big mushrooms?”

I take some time to reflect on this question as we continue up to our room. It gives me comfort to know that, since I could not possibly become more confused than I am now, I can only grow less confused later. I prove this to myself with calculus. Little theorems like this make my stay in Romania easier.

Diane, meanwhile, has solved the mystery and is silently shaking in her corner of the elevator. “Muscles,” she whispers when we're alone in the room. “He meant the men with large muscles.” And so we discover that Skanderbeg is the Romanian term for arm-wrestling ③. I peer into the hall with new curiosity, wondering how many asymmetrical large-armed men are slumbering in the hotel, flexing as they dream of victory. But the place feels completely empty.

We wake up in bright sunlight and descend to see the same faces who served us the night before, bringing out our breakfast with the same boundless solicitude. Breakfast, of course, is a cold plate, but it’s the most lavish one I've seen even in Romania, a country that takes cold plates seriously, a peacock tail of sliced salami, cheeses, radish, lettuce, ham, and even tiny little meatballs.

Coffee and eggs materialize the moment we sit down, and I seriously begin to wonder if we've been mistaken for hotel inspectors, clandestinely rating the place for a guidebook. We linger over breakfast, but either the Skanderbeg athletes are late risers, or they have already gone their way, and we never see them. I want to move in to this hotel and live in it forever. But there is a plane to catch, and the car is due back the next day.

Transylvania by daylight is lovely. There are lots of pine trees, lots of birds, and the roads are much better here. It is unfortunate that all over the province they have started clearing brush by burning, obscuring the mountains with a dirty haze. The smoke will persist for another couple of weeks, obscuring what would otherwise be a picture postcard view. Even with the haze, it's the most beautiful part of the country I have seen so far.

It takes us about two hours to make the gradual descent westwards. The Cluj airport is one of those little regional airports that has been caught unawares by the explosion of budget airlines in Europe at the turn of the millenium. The terminal is bare of any amenities, there is just a large open floor into which a long queue of people has been folded, waiting for Wizz! airlines to start check-in. I leave Diane to her discount fate and turn the car around for the long drive home.

I take a more southerly route back to see the Hungarian section of Transylvania. The Hungarians in Transylvania are called the Székely, and they have lived in these mountains since time out of mind. They like to fancy themselves lineal descendants of Attila the Hun, but it's more likely they were just a Hungarian tribe who drew the short straw on mountain sentry duty. Even through the Ceausescu regime they were able to keep their separate language and identity, and all the signs in this part of the country are in Hungarian ④. The look of the Székely houses and farms is very distinctive. One particularly lovely feature repeated from village to village are the ornately carved wooden gates and fences in front of every house, complete with a little steeple roof for the fence.

It is weird to see Hungarian signs in these little mountain villages. Imagine coming across a Swiss German enclave in the flat polders of Holland and you will understand the incongruity. The Hungarians, a steppe people, are not normally found at high elevation. It reminds me of the small and very culturally distinct mountainous piece of Poland in our own small corner of the Carpathians.

I zigzag down to the pretty city of Târgu Mureș, following a series of hairpin turns. A line of trucks is struggling in the opposite direction. In keeping with the charming Romanian custom, each has a little doily curtain hanging along the top edge of the windshield, and shows the driver's first name in big letters above the dashboard, so you can cheer him on. "Downshift, MIHAI, downshift!". At the apex of each hairpin turn is a giant billboard for the “XX-LARGE GENTLEMAN'S CLUB” in Târgu Mureș. My mind fills with questions, but there is no time.

East of Târgu Mureș, the mountains get serious again. I drive past a salt mine museum, and a lunar-like stretch that has been stripped completely clear of topsoil to feed a cement factory, before starting another descent into Gheorgheni. This is a small town so pretty and welcoming that I wish I could stay a few hours, but it's getting late in the afternoon, and I want to get out of the moutains by nightfall.

After Gheorgeni, the road turns into a winding canyon with breathtaking views that I cannot enjoy. All I can think about are the impossible overhangs of ice above my head. The road has been built along the bottom of a natural gully, and the snowpack that has accumulated on the edges all winter long is melting, leaving behind thick sheets of unsupported ice weighing hundreds of kilograms. These drip menacingly onto my windshield as I pass underneath, and every few hundred meters I drive through a shattered heap of ice fragments where a piece has detached and fallen onto the road.

I emerge from the canyons towards sunset at the town of Piatra Neamț. I am safely back in the flatlands of Moldavia, and the road ahead is ruler straight, leading some hundred kilometers to a town called Roman. But as the light gets dimmer, I notice some drivers behind me are flashing their brights. A quick stop at the side of the road shows me almost all the air has leaked out from one of my tires.

At this point, I've stopped making any assumptions about what to expect in the way of roadside amenities. Mercifully, Roman turns out to have an American-style service station with an air pump. But it has gotten quite dark, and I have seventy miles left to Botoșani. I have no idea how bad the leak in the tire is, but I when I put my ear to the wheel I can hear it hissing.

Night arrives and the drive becomes featureless, just a line of unreadable milestones and series of headlights passing me by. The Google map I have printed out is beginning to diverge from reality. None of the roads I pass are marked, and at intersections it is becoming difficult to tell which is the main road, and which is the spur.

I take what I believe is a turnoff for Botoșani, and find myself following a series of progressively smaller roads through thick forest. Mine is the only car around. The road crosses a railroad track and emerges back out in the fields again. It is pitch dark, but I can see as I pass that all along the road there are houses, and people sitting out in lawn chairs, and even some kids kicking a ball around. It's a bustling Friday night without a single street lamp. There's no light of any kind except my headlights, which illuminate the figures like ghosts as I pass by. People naturally turn to look at the car, which makes the impression even spookier.

If I spoke any Romanian at all, I would pull over and ask for directions, or help with the tire. But I don't; I'm an obnoxious American in a new car, destroying these good people's night vision, and disrupting their soccer game. I deserve my fate!

I see now that I'm on a grid of hard-packed dirt streets, and that this completely unlit place is a little town. I make my best guess about which road is the main one, and follow it back out into the empty fields. After a kilometer, it turns into a two-rut dirt road, and a little while after that, it fades into pasture.

I can see city lights and headlights far ahead of me. There's clearly a major road out there, and I even recognize the bright glow of Suceava over the horizon. It's a beautiful, clear night. But the tire is almost flat now, and there's no way I can change the spare in the dark. I'm starting to worry that I'll be spending a freezing night asleep in this field, or one like it.

Feeling low, I nurse the car back down the road, back to the strange unlit village, and try another direction. At some point a car passes me, which fills me with irrational joy, but it is just some local pulling into his driveway. For a while, the road looks like it might fade into another two-rut track, but it rallies and suddenly grows a coat of asphalt. A little further along, I see a milestone. Corni, 3 km. I know Corni! Corni is a tiny little village on the outskirts of Botoșani. The turnoff for it is on the main road that I've been looking for, the road which must be directly ahead. I'm saved!

And that is how become one of the few people ever to be glad to be back in Corni.

The last leg of the trip is pure luxury. The Botosani-Suceava road feels like a superhighway. I pass the giant DEDEMAN megastore on the outskirts of town, climb the familiar hill, enter the roundabout, and run right in to a police patrol. They are stopping all traffic, checking documents.

The cop signals me to pull over and takes a long look at my California license.

“Vorbiți românește?”

“Nu.”

“American?”

“Da.”

“Where are you going?”

“Home. I live in Botoșani.”

“You live in Botoșani?”

“Yes.”

There's a long pause as he looks at my license some more.

“What is an American doing in Botoșani?”

It's an excellent question. I wish I could answer it in any language.

Perhaps sensing that we've entered deep waters, or maybe because it's late at night and he doesn't feel like stamping anything, the policeman waves me through.

It means ‘bon voyage’.

① There is a long and exquisitely pointless debate between Hungarian and Romanian historians about who came up with this concept.

② Now known as Braşov, Sighişoara, Mediaş, Sibiu, Sebeş, Bistriţa and Cluj-Napoca. But though the names have been changed, and very few ethnic Saxons remain in Romania, the architecture is still as German as it gets.

③ Skanderbeg is the Albanian national hero, a military leader who spent years harrowing Ottomans in the fifteenth century. He was the subject of a popular movie which included a scene of him arm-wrestling an Albanian shepherd. This scene, or related legends about him testing his soldiers' prowess by arm wrestling, are the reason for the association. Why the Romanians are the only ones to use the name, while nearby countries call it things like 'armsport', is a mystery for the language geeks.

④ It's worth remembering places like the Transylvanian exclave of ethnic Hungarians whenever you hear talk about ‘age-old ethnic tensions’ making conflict in some part of the world inevitable. At the end of the Cold War, this region was a more natural flashpoint for ethnic conflict than comparatively wealthy Yugoslavia. The Székely had been oppressed for decades and subjected to forced Romanization. Hungary and Romania had a long list of mutual grievances, including territorial disputes over the Székely lands. But unlike in Yugoslavia, the respective leaders were not warmongers, and local skirmishes never turned into a broader conflict, though such violence would have been easy to rationalize.

| « No Evidence of Disease | Total Eclipse of the Sun » |

brevity is for the weak

Greatest Hits

The Alameda-Weehawken Burrito TunnelThe story of America's most awesome infrastructure project.

Argentina on Two Steaks A Day

Eating the happiest cows in the world

Scott and Scurvy

Why did 19th century explorers forget the simple cure for scurvy?

No Evidence of Disease

A cancer story with an unfortunate complication.

Controlled Tango Into Terrain

Trying to learn how to dance in Argentina

Dabblers and Blowhards

Calling out Paul Graham for a silly essay about painting

Attacked By Thugs

Warsaw police hijinks

Dating Without Kundera

Practical alternatives to the Slavic Dave Matthews

A Rocket To Nowhere

A Space Shuttle rant

Best Practices For Time Travelers

The story of John Titor, visitor from the future

100 Years Of Turbulence

The Wright Brothers and the harmful effects of patent law

Every Damn Thing

Your Host

Maciej Cegłowski

maciej @ ceglowski.com

Threat

Please ask permission before reprinting full-text posts or I will crush you.