| « Pursuing The Platypus | Green Arabia » |

لابد من صنعاء وان طال السفر - You must see Sana'a, however long the journey

The scariest thing I'll see in Yemen looms up at me before the plane has even landed. I have dozed my way from Abu Dhabi across most of the Arabian Penninsula, including the Empty Quarter, that vast uninhabitable sandbox in the interior were they didn't even bother to put in borders until fifteen years ago. That just looked like storybook desert, although there was an appalling lot of it.

But now the plane is well into its descent to Sana’a, the flaps are coming down, and all I can see below is bare rock from which every trace of sand has been scraped clean by an angry and pitiless wind. At last I understand why it took three billion years for creatures to come out of the sea and colonize the land. One glimpse of these rocks is enough to send anyone flopping back into the ocean, tail tucked between not-yet-evolved legs. Enormous stone fingers point upwards, reaching nearly as high as the plane. Between them are deep scars where water in some inconceivably distant past rushed to get the hell out of this forlorn place. There isn’t the smallest trace of life, let alone human settlement. It is the most pitiless, hostile, and frankly malevolent landscape I have ever seen.

The plane crosses a high ridge and at last, thank God, there are some dark dots of vegetation. Fearless people are irrigating this bit of Lovecraftian madness. The dots turn into rows, then clumps, and soon in places I can see the white scar of a road. The mountains subside into a broad, flat, dun-colored plateau. As the plane dips a wing to begin its final approach, I notice that the monochrome ground becomes boxy and pixellated out towards the horizon, where thousands and thousands of tiny cubes seem to rise out of the desert, as if the Yemeni landscape had a bug in its loader.

The cubes are houses, hundreds of thousands of them, all the same color as the ground. That is my first view of the city of Sana’a.

Sana’a is so strange and marvelous. If Yemen weren't in permanent crisis, the city would be awash in archaeologists, one of whom might even settle the question of how long people have lived here. Like Damascus or Jericho, Sana’a has a credible claim to be the oldest continuously inhabited city in the world. But what truly makes this place unique isn't its age, but its astonishing buildings. Old Sana’a looks like a gingerbread tribute to Manhattan.

While everyone else was content to build mud huts, tents, old caves or other basic dwellings, industrious Yemenis put up skyscrapers using only stone, mud, and lime. Confined by its protective wall from growing outwards, the city instead grew up, a forest of tower houses from five to nine stories high. These beautiful dwellings still stand, an ancient urban landscape where only the satellite dishes and metal water tanks tip you off that you are no longer in the Middle Ages.

It's hard to believe it when you're gasping for breath in a stairwell, but the tower houses of Sana’a are also quite practical. They allowed for a high population density within the city walls, permitted extended families to share a dwelling, and were handy in the real-life tower defense game against the hill tribes whose fondest activity for the past two thousand years has been plundering this lovely city.

Just as odd as the architecture is the city's climate. Tucked into the southwest corner of the Arabian Penninsula, near the mouth of the Red Sea, Sana’a is surrounded by some of the world's hotter deserts. By all rights, it should be a sweltering furnace like Riyadh or Khartoum. But because the plateau it sits on is over two and a half kilometers above sea level, the climate in Sana’a is positively mild. Northern Yemen may be the only place in Arabia where you can wear a sweater in June and live to write about it.

As the landing gear come down, I start to see details down in the streets. The pixel squares resolve into individual houses with chaotically unfinished roofs. Every rooftop has a low wall around it and has been capped off with a little cone of rubble. In between the houses there are long, stalled strings of cars, stretching out for kilometers. “Army checkpoints,” I think, but then I see that each thread of cars ends at a gas station. There are goats in the road, too. With their more flexible fuel requirements, they go where they please.

Right before the runway threshold, the plane passes a graveyard of Hind helicopters, rusted-out jet engines, and other airplane parts. The edge of the runway is lined with still functional helicopters, along with a row of big open hangars, each one sheltering a MiG fighter jet. It is terrifically windy. A vast Yemeni flag snaps in the breeze. Looking out at the barren landscape and tiny terminal, a single question wafts into my mind.

“What the hell am I doing here?”

Even with one tire out, the Soviet-made BTR-50 remains a formidable boot-drying platform

I've struggled for weeks to come up with a convincing irrationale for my visit, something more persuasive than the truth ("I really want to go"). The best I can do is steal an argument from my tour agency and stress that all the recent kidnappings have happened to Westerners who live in Yemen and have an established routine, not tourists who are tumbling through. I can cite the impressively thorough report on abductions in Yemen as proof that no tourist has been kidnapped since 2010, when two Americans were briefly detained. I can even picture the flipboard at the Yemen Ministry of Tourism:

[1382] days since last tourist abduction. Welcome to Yemen!

But it's possible tourists don't get kidnapped for the same reason there aren't many car accidents on the Moon. The few Westerners who come here tend to confine their visit to the old city, or the unequivocally safe (and remote) island of Soqotra. And there's no rule that prevents the bad people from changing their tactics if they get tired of staking out diplomats and English teachers. Given their scarcity, tourists in Yemen are about as inconspicuous as the Second Coming.

Kidnapping in Yemen used to be more fun. A disaffected tribe with a grievance would grab you for a week, play cards and chew qat, and then return you once the government had made whatever concession they were after. Lately, though, the kidnappers have been selling their victims to the local branch of al-Qaeda. Yemeni al-Qaeda is not particularly stabby, but they are serious about getting good value for abductees, and willing to wait as long as it takes to collect a solid ransom. They've kept some people for years. And they are probably no fun at all to play cards with.

The less vivid, but more likely risk is of just being in the wrong place when something bad happens. Maybe an American drone pilot will be having a rough morning in Nevada. Or maybe I'll be passing a government building as someone is detonating something to make a point. I promise myself to limit my time in the capital, try not to look too American (except from above), and avoid particularly risky spots like the Bab al-Yemen.

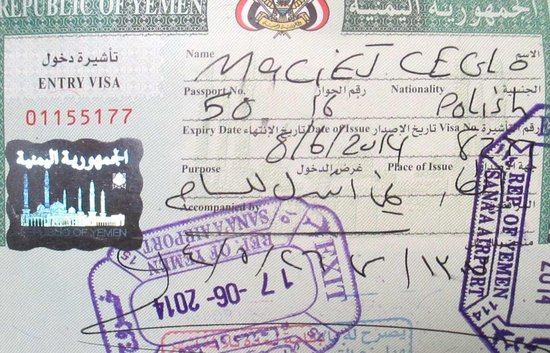

As my departure date approaches, I start to wake up with that hollow feeling that the body uses to tell the brain it's doing something stupid. The trip is getting uncomfortably real. Plane tickets are bought for actual money. My visa comes through, removing my best hope for weaseling out without chickening out. And then one bright morning I find myself in Abu Dhabi, overcrowded travel hub to the world, standing at the gate in a line full of grandfathers wearing headscarves. There aren't many of us foreigners on this flight, just an older Filipino man and a young Chinese couple. A woman behind me asks me if she's in the right line for Sana’a. It's the only time on this trip I'll be addressed by a Yemeni woman whose face I can see.

Sana’a International is not a sprawling, perfumes-and-Cinnabon kind of airport. My tour company has told me to look for a visa window as I enter the terminal, promising me it's easy to find. They weren't kidding. The arrivals hall is a single room, with passport booths at the far end and two holes in the wall on the left. The first hole is a currency desk, where a man in a synthetic suit sits quietly with an open briefcase of money in his lap. There is an exchange rate board hanging up, but all the numbers on it read 00.

The Chinese guy approaches me and quietly asks if this is a scam. I'm equally confused, but I figure if they're scamming us already we may as well just empty our pockets. He goes off to confer with his partner while I trade two hundred euro for a small mountain of very dirty green thousand-rial notes. I can see a figure on the baggage claim side of the window waving to get my attention, motioning for me to move to the visa window. My ride is waiting for me!

Showing my ignorance, I attempt to stand in line at the visa hole. Queuing is not done in Yemen; it demonstrates passivity and a shameful lack of seriousness about the task at hand. The correct approach is to press forward and assert your claim as loudly as you can; it's up to other people to shout you down. Friendly hands propel me forward and I shove my passport into the window.

A big fellow in the visa line asks me where I'm from. He's wearing an embroidered skullcap and the Abe-Lincoln-style beard of a devout Salafist.

“I'm American,” I tell him.

“Oh,” he says, visibly surprised.

“Where are you from?”

“Pakistan.”

I shake his hand heartily and introduce myself, and it's only a few minutes later that it occurs to me to wonder what a devout Pakistani dude might be doing in Yemen.

(And some days later, when I've had time to learn that Yemen is full of ancient mosques, and that scholars from all over the world come here to study, I will feel like an ass for assuming that this guy was anything but a religious student. I mention both reactions here to illustrate how useless my gut instincts are before I've even technically entered the country.)

I watch my passport circulate until it emerges from the wall. Yemen has never developed the fetish for bureaucracy that dogs so much of the Arab world. I notice on my visa that they got tired of writing out my name and just stopped halfway through. The border guards stamp me in and release me into the custody of my contact and driver, who have been waiting patiently in the terminal. Five minutes later, I've been bundled into the back of a Land Cruiser and we are heading downtown.

There are about a dozen military checkpoints between the airport and central Sana’a, but getting through them is a breeze. Usually there are three soldiers; one of them pokes his head in the car and Ali the driver says 'guest' or 'tourist'. Another verifies that the back seat is not piled with RPGs; the third dozes in the shade of a nearby armored vehicle. Ali has the checkpoints timed perfectly; he can roll through most of them without stopping.

I never do figure out the Yemen camouflage scheme. Each checkpoint seems to have its own look. Most popular is a 'leopard' camo (bright yellow background with dark shapes), but the visually arresting purple and fuschia combo comes in a strong second. Very occasionally an iconoclast soldier dresses in colors that might be found in nature. The armored vehicles at the checkpoints are similarly festive. Not many of them look ready to swing into immediate action. One APC still has the cover on its gun barrel, hanging off limply like a burlap condom.

In between the checkpoints is a broad road full of traffic, noise, and blowing dust. Pedestrians position themselves like pit crews, ready to ask for alms or sell trinkets whenever the cars slow down. Women in full niqab go from car to car, carrying ill children. Small kids run over trying to sell a box of tissues or a pitiful flower. The traffic never really stops or even forms into recognizable lanes; people just squeeze in and around obstructions as necessary. Whenever we pass a truly epic tangle of cars, it inevitably marks a gas station. None of the pumps are working.

The transition to Old Sana’a is abrupt and astonishing. The ramshackle cinder block buildings turn into iced gingerbread houses, and suddenly I'm in the middle of the pictures that I have admired for so long online. Central casting has even provided a camel; he stands meditating across the street from the hotel.

At the hotel gate I'm introduced to Fouad, my guide, and I have to bodily push him back into the courtyard to avoid breaking the Slavic taboo against shaking hands over a threshold. It's rude and awkward, but I'm in a place where I can't afford to take chances.

The Felix Arabia is the only hotel that is still open in the Old City, and today I will be its only guest. They have graciously put me on the fourth floor, where I'll have views of the entire city, and Fouad waits for me to make the long climb upstairs. I can really feel the altitude; my legs start to wobble after the second flight of stairs, and I have to stop at all the landings to catch my breath.

Fouad is a slight guy around my age, with wide-set eyes and a wispy moustache. He's dressed in a coat and slacks rather than the thawb-and-dagger outfit that most men here seem to favor. Almost as soon as we start walking, he turns to me and asks:

"Tehuzzin?"

"What does that mean?"

"This is an important phrase. It means, do you chew qat?"

"Well of course! When in Yemen!"

We settle on a plan. Fouad will show me the city, we'll have lunch, come back to the hotel, chew some qat, and then take a walk again in the evening when the light is at its prettiest.

Walking around Sana’a as a white dude gives me an inkling of that it's like to be famous. As we follow the narrow streets, I see my own pie-eyed reaction to the architecture reflected in the faces of passing children, who are just as surprised to see a foreigner as I am to see a six-hundred-year-old skyscraper. Adults are more circumspect, but it's obvious that I am attracting attention. Fouad is an excellent minder. He keeps me moving, unobtrusively but efficiently, through little street after little street. A lot of people come up to welcome me to Yemen. Kids and a few adults ask me to take their picture.

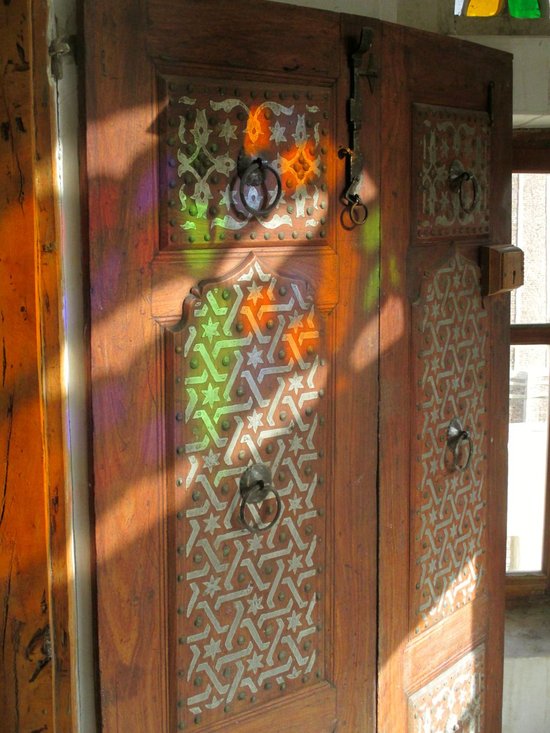

It's not any individual building that makes Sana’a so incredible, but rather the cumulative effect. The towers are full of curious details.

From the outside, the buildings look like confectionery. The icing is decorative white trim made from lime. There are some ornamental and structural features that I see again and again. Many houses have a sort of carved stone cage affixed at some of the windows that serves as a cooling station for meat or water. It’s set up so that the breeze will blow through and chill whatever's inside. There is a lot of strategic draught management in Yemeni architecture. While the city can get hot, it is also nearly always windy, and this is fully exploited to keep structures cool.

There are also highly decorated, carved wooden boxes mounted onto some of the higher windows. These were—are—a way for unveiled women to look out into the street without raining shame down upon their household.

(The veiling thing is seriously creeping me out. I've been in Yemen's capital city for hours and I have yet to see a woman's face. They move like black ghosts through the streets of Sana’a, and the niqab works as intended—it's really easy to forget that they're even there. On this one issue I've hit the limits of cultural sensitivity. Carry an AK-47, chew qat, wake me up at four with an ear-splitting call to prayer, I don't care. But this veiling business has got to go.)

Many of the houses have a white vertical gutter coming down from an upper floor, mercifully no longer used, which once served as a sanitation system. The city used to be a far more pungent place. Human waste would be collected, dried, and used to stoke fires in the large Turkish baths, thick hemispherical structures that look like vast bread ovens placed in the landscape.

Near the hotel we pass a large walled garden, about a city block in size. It is divided into numerous small lots. Fouad explains that each tower house got its own allotment of land, to use as a vegetable garden or to grow herbs to sell. The practice is falling into disuse as families move out of the Old City. The ground belongs to the nearby mosque (in a perpetual endowment called a waqf) and the garden is irrigated by water from the ritual ablutions required before prayer. It's a small example of how self-sufficient the city used to be, before half the country tried to move here.

"So what do you think of Sana’a so far?" Fouad asks me.

“It's incredible. I've never seen anything like it. But I am just a little bit afraid.”

He stops and looks at me seriously and says:

“Don’t worry. Don’t worry at all. We are together. If something happens to you today, it will happen to me. If you die, I will die with you!”

I would also have accepted “there's nothing to worry about”, but I'm touched by how seriously he answers me. Life is very difficult for people here right now. There are no jobs, no fuel, and no sign that things might get better. The tourist sector is dead. Walking me around Sana’a today is the first paid work Fouad has had in three weeks. He has more pressing problems to deal with than the vague anxieties of a pampered visitor. But he's looking at me with real concern.

One thing Arab and Slavic cultures share is a belief in the comforts of fatalism. Sometimes it's nice to sink into the inevitable like an overstuffed armchair.

"It's all written up there," I suggest, pointing melodramatically at the sky.

He brightens.

"That's exactly right. Maybe we die today, maybe we live another fifty years. It is already written. Insha'allah."

“Insha'allah”

And he takes me by the arm to go buy some qat.

The qat seller is a gentleman sitting cross-legged with a big black sack on his lap. He opens it to reveal individual bags of leaves, the kind of vaguely salad-like baby greens you would expect to pay twenty dollars for at Whole Foods. Part of the ritual of buying qat is a minute botanical examination of the plant. The seller lets the qat out of the bag long enough for Fouad to reject half a dozen packets. After some back and forth, the price settles at two thousand rials (four bucks) for two bags of young leaves.

Physiologically qat is a stimulant, but in Yemeni culture it plays a social role akin to alcohol. Qat is what you buy for your guests at a wedding. Qat is what you blow your paycheck on. Qat is what keeps you out late with your good-for-nothing friends. You can chew qat alone, but the best way to enjoy it is with a group of other men, seated together in a mufraj (the Yemeni lounge and chillout room). Ideally you set aside a block of four or five hours in the afternoon to get nice and lit. People who can rarely afford qat might stay up all night to chew it, minds racing. Habitual users usually start their session after lunch and spit out the wad before bedtime. You're not supposed to chew qat on an empty stomach, and since you can't really eat (nor do you feel hungry) once there is a big lump of the stuff in your cheek, it's normal to wait to chew until after the big meal of the day.

We take our new stash to a restaurant, a big tiled room with one wall open to the street. Women are selling fresh-baked bread in the doorway, and Fouad buys us two disks the size of manhole covers, thin and still very hot. Yemeni bread is unbelievably tasty for the first hour after baking; after that it turns into a regular kind of chewy pita. A cookpot the size of my first apartment simmers away on a platform by the entrance.

The restaurant is dark, dirty, and minimally furnished. There’s a jerry can of water at each table, but Fouad warns me not to drink it. It is for Yemeni stomachs only. While he's off finding me bottled water, the waiter brings over a little boiling iron cauldron of saltah, the Yemeni national dish. There's a yellow foam on top that looks like melted cheese.

Saltah is a meat stew. The yellow foam is whipped fenugreek (hilbeh), a bitter and mucilaginous herb that people tell me is an acquired taste. It is supposed to do wonders for the digestion. The server brings us several bowls of room-temperature broth that we can pour into the cauldron to moderate the boiling.

The protocol in Yemen is to eat with your right hand. The bread serves as a heat shield for the fingers, and you depth-charge your way in and try to grab pieces of meat without scalding yourself or your neighbors. Maybe we eat the fenugreek layer first, or maybe I adjust to the taste and start to like it, but by the end the meal is delicious.

On my way out, my path is blocked by some other diners, who are calling out to me. It takes me a second to process what's going on.

"Please take our picture. Welcome to Yemen!"

This kind of thing happens everywhere. I can't overstress how welcoming the men in this city are to visitors. Yemenis love their country, and they show great affection to those who make the effort to come see it.

After lunch, a man's fancies naturally turn to tea. Fouad asks me if I want to sit and drink at a tea stand, or take the stuff to go in a plastic cup. We're very close to the Bab al-Yemen, the main gate where the Old Town connects to the heart of the road network in the new city, the one place in Sana’a that I don't care to linger. So I suggest we drink on the run. Like an idiot, though, I reach for an actual glass of tea instead of the plastic cup that has been poured for me.

It's a beautiful day. It feels frankly foolish to be worried here, like some hayseed in New York City terrified he'll be mugged the second he sets foot in Times Square. The mood on the street is the opposite of tense. People are strolling comfortably along the broad plaza, and the Bab al-Yemen itself is lovely, a striped layer cake of colored stone. I sit, grin, and silently burn my mouth in my haste to get through that damned cup of tea.

The hotel has a mufraj right off of the reception desk and for the moment, we have the space to ourselves. Fouad shows me how to relax in the Yemeni fashion: you lie on your side, with your elbow on a bolster, and place one foot on top of the other so that one knee points upwards in a kind of jaunty Tom Selleck pose. It's important not to point the soles of your feet at people. Yemeni men have all kinds of techniques (which I mercifully don't have to master) to avoid upskirt situations while sitting or reclining.

The qat lesson is easier than the sitting lesson. You chew the leaves and softer stems down to a pulp, then push that mass into your cheek. The thicker stems go in the trash. You let the chewed-up leaves sit in your cheek and work their magic.

The hotel manager walks in on us and chastises Fouad for letting me eat qat out of a plastic bag. This is no way to introduce a stranger to qat! He takes my stash and brings it back a minute later, washed and neatly arranged in a cloth.

Qat is no taste sensation. You can enjoy a similar experience at home by sprinkling Sanka on a houseplant. There's a definite astringency to the leaves that makes me pucker my mouth and have to take many tiny sips of water. But it's also not particularly vile, nowhere near as bad as tobacco.

"How do you like it?" Fouad asks.

"It's not as good as the fenugreek," I tell him. He clicks his tongue impatiently and tells me to wait an hour. "You'll be flying like a bird!"

Some of the other hotel staff are starting to arrive, each man with his own bag of qat in his hand or tucked into his shirt. One thing I quickly come to love about Yemen is the absence of small talk. People may eventually ask you where you're from, what you do, and even what you think about the weather, but not before they've tried you out in some real conversation.

Topics under discussion today include the World Cup, the economically devastating expulsion of Yemeni workers from Saudi Arabia in 1991 (when Yemen's president rashly backed Saddam Hussein), the wisdom of the adage ‘give praise in public, criticize in private’, and whether or not it's an insult to praise the beauty of a foreign man's wife in his presence. This last point is raised by the desk clerk, who has learned to say “your wife is very beautiful” in five languages and argues passionately that there's nothing unseemly about stating facts.

The conversation ebbs and flows. These guys spend every afternoon together, there is no time pressure. People ebb and flow too; sometimes a man will come in and just sit for a while without speaking, then leave the room. Women chew qat as well, but they do it in their own world, which I will never get to see.

At one point when it's just me and Fouad again, he says:

“You know how you've been saying today you're Polish and American?”

“Yes?”

“Maybe as you travel outside Sana’a, don’t talk about living in America. Maybe it’s better to just say you’re Polish.”

“Is it dangerous to say I’m American?”

“No, no, it’s fine. There’s no danger. Just for some people, maybe it’s better if you say Poland.”

“Thanks, Fouad.”

“No problem.”

The afternoon light has turned Sana’a into a different city, and I'm on the right drug to appreciate it. The slanting rays bring out all kinds of detail in the buildings, and the qat is making me feel chatty. Only the difficulty of Arabic grammar keeps me from talking Fouad's ear off. Every man we pass is boasting a golf-ball sized lump of qat in his cheek, and it's comforting to know that in this small way, I fit in.

Most of the men I see on the street are wearing either a thawb or a shirt with sarong-like skirt that wraps around the hips. They also wear a Western-style suit jacket, which gives them a curiously elegant and formal look. Nearly every man wears a jambiyah, the curved ceremonial knife so emblematic of the country, positioned right at navel height. The women, as I've said, are uniformly veiled in black.

Fouad takes me into a tower house that has been restored and set up as a kind of museum. On the ground floor are the three things every tower house required: a grain store, a mill wheel, and a well. The second floor has a kitchen. The third floor has a film crew. They are shooting a period soap opera and are very unhappy with our presence. Ramadan is coming up, the biggest month for television in the Arab world, and they are on a tight schedule. We negotiate passage to the upper floors with the promise that we'll be quiet and leave almost immediately.

Before the days of television crews, the lower residential floors were reserved for womens' quarters, the men lived above them (of course), and the top room in the tower was set aside for an opulent mufraj, with cushion-lined walls, elegant teapots and panoramic views of the city. In between some landings there are cubbyholes that look big enough to hold a large dog. This is where servants would curl up to sleep.

There are some clever details to these houses. The windows are set low to the floor to keep the sun from heating up the rooms too much at midday. Above them are beautiful semicircles of stained glass, called moon windows. Many of the windowpanes in the stairwells are made from alabaster instead of glass, preserving privacy while letting in a beautiful white light.

There's even a neat system for storage. "Closets" and pantries are recesses in the wall up near the ceiling. To get to them, you pull out sliding planks mounted into the walls that form a little temporary staircase.

From the roof, the city is breathtaking. I mean that literally. I am gasping from the altitude, and it doesn't help that the steps in these houses are so exceptionally steep. I enjoy the view in every direction while Fouad points out the highlights. The gigantic, kitschy mosque in the distance was built by Yemen's former strongman Saleh, to make sure the country would always remember him. It's rumored to be full of weapons, and there's even said to be a tunnel connecting it to the presidential palace. Saleh's old buddies refuse to let the army come inside. Closer in is the Ministry of Defense, where fifty-six people died in a bomb attack in December. And just over this nearby rooftop is the American embassy, which was attacked by a mob in late 2012. At this point Fouad has to take a call, and I am relieved to have him stop pointing things out.

Sana’a is a city full of problems, but the biggest problem is hiding under our feet. That well in the basement is never going to draw water again. Sana'a is on the point of running completely dry.

There are no rivers in Yemen. Sana’a used to get by with wells, but back then Sana'a was a much smaller city. In modern times, the population has exploded, from sixty thousand residents in the nineteen forties to estimates of over two million today (the country is too broken for an actual census). The days when you could sink a well from your basement are long gone.

In the seventies, you might hit water after drilling a few dozen meters. Today there are wells going dry that are over a kilometer deep. The water table is dropping by two meters a year. The city is drinking fossil water deposited thousands of years ago, and what's worse, using it for agriculture. Part of the urgency in my trip is the worry that there won't be a city to visit for much longer.

In a less broken country, the water crisis would dominate every facet of public life. In Yemen, public life is a joke. The government is so corrupt and paralyzed by crisis that it can't perform the most basic tasks. The city's wells are completely unmonitored; no one even knows how many there are. Private owners will keep drilling for as long as they can, but at some point even the deepest wells are going to run dry. And then something awful will happen.

Old Sana’a may survive as some kind of a museum exhibit, but in a matter of years (not decades) the rest of this vast city will have to move or die. The situation is so dire that the previous government seriously considered moving the capital to the stifling Red Sea coast, or somehow piping desalinated water over the three kilometer high mountains that separate the capital from the coast, at inconceivable expense.

It's hard to look at a city this old and imagine it could just go away. But the numbers don't add up. There isn't enough water here for two million people. There certainly isn't enough water for two million people and agriculture. But how do you tell a desperately poor farmer to stop growing qat? And who is going to make him listen?

The streets have grown livelier now that the sun is not so high. The market is filling up with silent black ghosts. Most of them have toddlers in tow. Fouad takes me through the pungent spice market to the large Souq al-Milh (salt market) where everything is on sale, from men's decorative daggers to textiles to cookware. This is technically the most touristed spot in Yemen, yet there's not a single t-shirt store or even postcard stand in the place.

Having just come from Morocco, I'm used to mild commercial harrasment and the kind of instant street friendships that end with one party bringing home a carpet. So Sana’a really puts me off my stride. Merchants who yell out 'hello' really just want to say hello. If I stop and engage them, they ask me where I'm from, welcome me to Yemen, and send me on my way. A lot of people insist I take their picture with no expectation that they'll ever get to see it themselves. It's a upside down world for a tourist.

Watching Fouad teaches me how to move through public spaces. You never stop to let people through; you just adjust your pace and path to squeeze by as necessary. People in tight spaces will flow like a liquid, and it turns out that if everyone presses forward, the system works. The only way to screw up is by being unpredictable in your movements, or trying to apologize. People who need to get through more urgently will yell or honk as they're coming up behind you. Tomorrow I'll learn that this system applies also to driving, and works just as well. For now it's enough to experience it on foot.

We stop in at the Great Mosque, the only place that I don't feel fully welcome. I am only allowed to step onto the threshold. Fouad urges me to take a picture, though I would prefer not to. Someone bumps my knees with the shoes they're carrying in their hand; I can't tell if it's a passive-aggressive gesture or not, but I'm happy to move on. The Great Mosque is more impressive for its antiquity than its appearance; like many of the earliest mosques, it is very plain and somewhat blocky. This one was built while Mohammed was still alive. I look up with apprehension at the massive loudspeakers on the minaret, pointed directly at my hotel room.

We stop at this great little cafe—you've probably never heard of it—that used to be a caravansarai. The building is an old courtyard where merchants coming in from the city would tie up their camels and rest. Now a man in the doorway makes the most delicious coffee I have ever had, a kind of Yemeni frappucino with evaported milk, cinnamon, cardamom, sesame, and a whole lot of sugar. And here is a pair of European tourists, the only sighting of the day! Russians! For whatever reason, only the former Warsaw Pact and Italy are still visiting Yemen. Even the Germans, normally hard to rattle, have moved on.

Like a gentleman, Fouad gets me back to the hotel before nightfall, and I have the chance to survey the place. There is a Russian book on the table—Mohammed, Prophet of God. A sign in the bathroom reminds me in English that I am in a "traditional Moslemic society" and should take care not to parade naked in front of the low windows where half of Sana’a can see me.

My last appointment of the day is down in the courtyard, with Tina Zorman, who along with her husband runs the tour operator Eternal Yemen. The days when you could travel in Yemen by yourself are gone, and now every foreigner needs an itinerary, a driver, and a security escort, all approved by the Ministry of Tourism. Tina is coming to brief me about my itinerary and answer my questions before sending me out into the countryside.

I have been looking forward to our conversation, hoping a fellow Slav might help me get my bearings and give me a culturally reassuring point of reference. But Tina is a Slovenian woman with an Arab soul. As if to demonstrate the verbal effects of qat, she monologues for over an hour before we get anywhere near the topic of my upcoming trip. I realize that if I want to be a part of this conversation, I will to have to fight my way in.

The itinerary is pretty much fixed; a standard loop through the small triangle of Yemen where tourists are still allowed to go. I have already met my driver, Ali, who I will come to recognize as a prince among men. The security situation is safe, Tina assures me, but she likes to wait until the last minute to submit the itinerary and request the permit. "It's better not to give too much notice." That means we won't find out until tomorrow morning how many soldiers are coming on the trip.

I know from reading a blog post by Wandering Earl (a guy who looks like he would drink your last beer out of the hostel fridge) that American citizens get a military escort in Yemen. Unfortunately, a few weeks before my arrival the Tourism Ministry expanded this policy to cover all visitors. Even Polish citizens are no longer safe from the protection of the Yemeni armed forces.

When I was planning my trip, traveling with soldiers sounded like it might be a fun, wacky thing to write about. But now, on the eve of my departure, it just sounds like a hassle. It's hard to keep a low profile with a squad of soldiers by your side. Tina is even less happy about it than I am. She will have to feed this private army and supply them with qat and a place to sleep.

(A week later, when I find myself surrounded not just by soldiers, but by an entire company of tanks, with a Hind helicopter buzzing over our heads for protection, I'll think wistfully back on this moment. The government of Yemen cannot guarantee your safety, but it makes sure you'll go down swinging.)

The power goes out halfway through our talk, and we're left sitting in dark for a while, until the hotel can spin up its generator. “You're going to want to buy some batteries and a flashlight. This happens pretty much every day.”

That evening I wait up in my room for the generator powered lights to go off. Blackouts are so common in Sana’a that the hotel has installed an entire parallel lighting system that runs off the generators. Unfortunately, there's no way to switch these lights off. I feel very conspicuous, silhouetted in my turret against the night sky while I can't make out anything of what's happening in the streets below. The situation perfectly captures what it feels like to visit Yemen. Outside the city is dark, except for the far-off flashing neon of a modern casino hotel. There are invisible people down in the streets yelling at each other, and from time to time I can hear the sound of running footsteps. A red tracer bullet drifts up over the Presidential mosque, a few miles away. As best I can tell, this is just a normal evening in Sana’a.

Eight more days to go!

| « Pursuing The Platypus | Green Arabia » |

brevity is for the weak

Greatest Hits

The Alameda-Weehawken Burrito TunnelThe story of America's most awesome infrastructure project.

Argentina on Two Steaks A Day

Eating the happiest cows in the world

Scott and Scurvy

Why did 19th century explorers forget the simple cure for scurvy?

No Evidence of Disease

A cancer story with an unfortunate complication.

Controlled Tango Into Terrain

Trying to learn how to dance in Argentina

Dabblers and Blowhards

Calling out Paul Graham for a silly essay about painting

Attacked By Thugs

Warsaw police hijinks

Dating Without Kundera

Practical alternatives to the Slavic Dave Matthews

A Rocket To Nowhere

A Space Shuttle rant

Best Practices For Time Travelers

The story of John Titor, visitor from the future

100 Years Of Turbulence

The Wright Brothers and the harmful effects of patent law

Every Damn Thing

Your Host

Maciej Cegłowski

maciej @ ceglowski.com

Threat

Please ask permission before reprinting full-text posts or I will crush you.