| « Sana'a | Ta'izz » |

It was a dark day when Islam met the loudspeaker. All travelers to the Middle East discover that this normally self-assured religion gets insecure in the small hours of night and feels it has to rehearse its foundational beliefs, in public, at 190 dB.

Hey, wake up. God is great.

Hnnnnghh. What’s happening? Where am I?

Hasten to prayer! Hasten to success!

Islam, is that you?

I bear witness that there is no god but God.

Jesus Christ, Islam, it’s four o’clock in the morning!

I bear witness that Mohammed is the Prophet of God.

You loudspeakered your tenets last night!

Prayer is better than sleep.

They actually add this line for the dawn prayer. Even the Prophet had trouble getting up at this hour. The same loudspeaker that assures you “prayer is better than sleep” prevents you from being able to test the claim. It’s like writing out “carrots are better than chocolate” on a vegetable platter, while you hide the dessert cart.

Every review of the Arabia Felix hotel warns about the call to prayer. Yemen’s oldest mosque is just steps away, and those loudspeakers are going to keep running for as long as there’s a working generator and a drop of diesel left in the capital.

But as cranky as I feel, I know the real villains in this story are the sun worshippers of ancient Arabia. It’s their fault that Islamic dawn and sunset prayers couldn’t be held at the most logical time, when the limb of the sun is just crossing the horizon. It is expressly forbidden in Islam to pray at sunrise, or sunset, or at high noon, specifically to prevent sun worship.

My reward for waking up for fajr (4:12 AM!) is a chance to watch Sana’a come to life. There is a peaceful, soft light that suffuses the old town. It intensifies quickly, at this low latitude, until the sky is perfectly blue. When the sun itself clears the western mountains, it bathes the old city in yellow light, and the world looks like it has been dipped in honey. You can see what made the sun worshippers such a threat.

Ali the driver ① is waiting for me downstairs after breakfast, and he has brought terrific news. The tourism ministry has relented and will permit us to travel without a military escort. For the next seven days (until we wind up in a tank convoy) there will be no soldiers following behind us and no soldiers chewing up our qat in the back seat of the Land Cruiser. This is an unexpected victory, and it’s important that we get out of the city before anyone at the ministry changes their mind.

The first order of business is collect and photocopy the sacrosanct travel document that will get us through the road checkpoints ahead. Ali is such an old hand at this that he ends up making exactly the right number of copies, with one sheet left over at the end of our journey for me to keep as a souvenir. He piles the copies up behind the windshield as a talisman. Early on, while the pile is still thick, the mere sight of it is enough to get us waved through most checkpoints. As the pile grows slimmer, its power wanes, until even fifteen-year-old Houthi rebel kids start fussing over its fine print. But today we are unstoppable.

The road out of Sana’a is a broad and straight boulevard lined with stores and the half-finished mansions of the rich. The 2011 revolution brought a whole new group of kleptocrats to power, and they are busy trying to out-build each other. Traffic is light, and it doesn’t take us long to reach the outskirts of the city, where the road almost immediately begins to slalom up into the mountains.

Of course Yemeni driving is crazy. But there are two things in particular that make an impression. One of them I notice right away, while the second takes a little while to sneak up on me.

The first thing is the speed bumps, artisanally crafted obstacles that are the tangible expression of Yemen’s entrepreneurial spirit. You can’t drive half a kilometer on the Sana’a—Tai’zz road without hitting a speed bump. People find creative ways to put an obstacle in the road and then position themselves on top of it with a wheelbarrow of carrots, or a crippled relative, or a cooler full of cold water. The type of speed bump tells you a bit about who you’re dealing with. Peddlers on a budget shovel dirt into a line across the road, letting the passing traffic compact it down into a kind of ridge. This kind of speed bump is cheap but labor-intensive. You have to renew it every few hours. Those who have money to spend lay a big rope across the road and cover it with asphalt.

The bump builders are considerate enough to mark their work on the side of the road with rocks; otherwise the obstacle in the road would be impossible to see in time for any car to slow down. Driving on the main road becomes a sequence of stops and starts. You accelerate to top speed between the bumps, then brake as quickly as possible to spare your suspension.

The speed bumps are illegal and highly annoying, but no one seems to resent them. People caught in the act of piling up dirt don’t get honked at. And the bumps do help keep down speed on the long straightaways.

The second, less obvious thing about driving is just how good the roads are. It takes a while for this to register, partly because of the speed bumps, but eventually I notice that even on the steepest mountain passes the paved roads are smooth, well-drained and well-maintained. They may not have any markings or guardrails, and the traffic on top of them may be lawless, but someone is building these roads to a very high standard.

Blogs I’ve found suggest—vehemently, repeatedly—that this is not the case everywhere in Yemen, but the fact that there are good roads anywhere is surprising, given the near absence of other public services.

Ali is a wonderful driver. He’s not timid about getting from point A to point B, but he doesn't let anything faze him. He even wears his seat belt. The closest I see him come to road rage is a conspiratorial “can you believe this?” look when some other driver has nearly ended our lives. On the rare stretches of open road, he's content to float along at 90 km/h, singing along to ‘oud songs by Hamoud al-Smah, chewing on qat if it's after two PM. In those moments, I feel like I’m in the establishing shot of National Geographic documentary. Everything about the landscape, the music, and the clear, bright sunshine is just right. I envy the drone pilots who get to see this landscape every day.

The road from Sana’a to Ibb is a series of impressive valleys and ridges. Every time we climb a ridge, the landscape before us gets a shade greener. And each valley has its own special crop. The roadside stands show you what’s growing. Close to Sana’a the ground is still arid and it’s mostly squash on sale. Further south, we start passing fields of qat, recognizable by the white protective netting suspended over the plants (whether this is to protect against pests, or wind, or frost, I can’t tell. Qat in other regions grows on shrubs with no netting). After the qat comes a valley of potatoes. By the time we reach Ibb, the landscape has changed from semi-arid to downright green. There are orchards and big shade trees. There's even grass growing by the side of the road, something I never imagined could exist in Arabia.

The valleys are heavily terraced. From a distance, the land looks like an architectural model, or a low-resolution computer rendering. The terracing is done with drystone. Over centuries, people have laboriously blasted, chipped and stacked the mountain rock into a staircase series of shelves, trying to maximize their opportunities for agriculture. Yemen has a tiny proportion of arable land, most of it squeezed into this corner of the country, and people use every inch of it. The backbreaking labor of generations is written into the landscape. More impressive is that these terraces have to be constantly maintained. It takes only about two years for a neglected field to fall into disrepair, at which point all the stones must be re-stacked from scratch. And I don’t see any neglected fields.

The hilltop villages are even more remarkable. They consist of dozens of tower houses, also made from stacked drystone. From a distance, they bear a striking resemblance to towns ins upland regions of Provence, or Italy. It’s only up close that you register the absence of little cafés, or churches, or carefully tended flowerbeds. No doubt this is what Provence or Tuscany looked like in the 19th century, before the rise of international tourism turned those regions into a wealthy living museum.

In France they make a huge deal out of their fortified hill towns, called ’villages perchés’. Built on difficult terrain where marauders were more plentiful than water, they evolved under the same conditions as the stone towns of highland Yemen. Now they consist entirely of antique stores and quaint cafés. There are strict rules about what you can and can’t build in order to stay true to the character of the place. Not many families live with their livestock anymore.

Around noon we stop for lunch at a roadside restaurant. The word ‘restaurant’ is a little deceptive, evoking pictures of checked tablecloths, salt shakers, and little flowers in tiny vases, rather than men with guns sitting on a mutton-stained carpet, so let me set the scene a little.

The typical Yemeni eating establishment resembles a commodities trading floor on one of those days they call ’Black’. There is not a lot of furniture, but there is a lot going on. We enter a dark room that has some bare cafeteria style tables, each covered with a plastic sheet and with a plastic cooler of water at one end. There is a display case of food near the door, but people seem to be ignoring it, and its contents bear no relationship to the food I see people eating.

The restaurant is full of men all wearing the traditional outfit of skirt, jambiyeh and sport coat. Some of them have an AK-47 slung across their shoulder, barrel pointing upwards. The guns tend to swivel around as people eat and add a sword-of-Damocles excitement to the meal. Knowing that you might get shot at any moment really heightens the flavors of a Yemeni luncheon. Around the tables there are carpets, and many of the men choose to eat while reclining on the floor.

In Yemen you don’t really talk while eating. This makes the heavily-armed diners staring up at me from their carpets seem even more menacing. The wait staff, on the other hand (at least I assume that’s what they are) run round shouting at the top of their voices. Almost everyone has already purchased a bag of qat, which they'll start chewing after lunch. The qat is leafy and kind of bulky, and comes in a colored plastic bag. Some men tuck it under their shirt, so it hangs over their belt like a paunch. Others carry it in their hand. The effect is to make everyone look excessively health conscious and obsessed with salad.

Ali motions me to a row of sinks at the back of the room where we can wash our hands. He speaks a neighborhood dialect of Yemeni Arabic that even some other Yemenis have trouble with, while I speak a halting form of the literary language understandable only to myself. We’re at an early stage in our relationship where he relies a lot on sign language and exasperation.

He finds us a table and I position myself so I’m not looking down the barrel of too many rifles. An elderly man seated next to us is just finishing his meal, his eyes fixed on mine, his white beard bobbing up and down as he chews. Ali leans across the table and asks me, "What would you like to eat?"

I find the question delightful. Caviar to start. Perhaps a clear court-bouillon, toast fingers, suprême de foie gras, smoked duck tongues, and an endive salad. Strawberries in non-alcoholic kirsch.

“Ali, I’m in your hands. Anything!”

“What?”

"Whatever you like.”

“What?”

“Anything!”

“What?”

“Anything! Chicken!”

“Chicken?”

“Chicken!”

Ali grabs a waiter and demands chicken. A young boy has already materialized with big plates of rice and two cans of Pepsi. Coca-Cola may be famous for having distributors in the remotest, least accessible parts of the world, but in this corner of the world, the Cola Wars ended differently. Pepsi is king. ②

As two halves of a roast chicken are brought into the presence, Ali gives me a searching, penetrating look. For a moment, something between us hangs in the balance. It's like he's examining my soul. Then he rises from his chair and returns with two plastic spoons. I give him a hurt look and push the offered spoon away. Are we not men? Is this not Yemen?

I’ve been using my right hand all my life, but eating non-sticky rice with it makes new demands on my dexterity. Ali has an impressive way of forming three fingers into a scoop and neatly, almost surgically, removing a portion of rice from the edge of his dish. His plate looks like a pie chart, with a slowly growing wedge of negative space tracking his progress through the meal. My side of the table looks like someone has been repeatedly smashing my head into the food to try to get me to talk.

Nervous about using my hands wrong, I forget to pace myself. Meals here tend to arrive in stages, and I’m already pretty full when another child waiter arrives with big disks of hot bread, a kind of bean dip, and a salad of finely diced tomato and cucumbers. Lunch is a big meal in Yemen. For a lot of qat chewers (which is everyone), it’s the final meal of the day.

I make stomach-exploding motions to persuade Ali that I’ve gotten enough to eat. He leads me back to the row of sinks to wash the grease off our hands. One of the sinks has been converted into a dedicated qat-rinsing station. The others are available, but there is no soap.

In America, I would go wait in line and ask the host at the front of the restaurant for help. Now I get to watch how things are done in Yemen.

First, we need numbers. Ali collects a quorum of other dissatisfied diners. The nimblest of the group captures a waiter, who quickly folds under interrogation and gives up the owner's name. We bellow this out loud. The owner is in the back room, stirring something massive in a cauldron. He bellows back at us, and Ali charges in to begin negotiations.

There is some yelling on both sides, then a final loud cry from the owner. A young boy shoots out of the kitchen and out the front door, running at top speed. Ali follows him at a more dignified pace. Soon I see Ali coming back my way, holding a packet of laundry detergent in the air. Someone slices open its belly and spreads the contents across the sink tops in a fat white line. As the foreign guest, I am invited to wash my hands before everyone else. Another young boy chases me down with a paper napkin so I can dry my hands.

This little episode captures something I’ll see over and over again in Yemen. Faced with a problem, you find out who is in charge, escalate to the highest level of authority present, and communicate your sincerity by vigorous yelling. There is always a phalanx of sons (and presumably a similar, hidden number of daughters) who can be deployed as messengers, sent on errands, or otherwise made useful. Everything is done with a level of verbal vehemence that would involve grief counseling and possibly lawsuits back in the United States. People are able to operate at emotional temperatures that would melt down an American.

If you asked me what I had witnessed, I would say angry people with guns had nearly come to blows over handwashing. But of course it’s just me who is miscalibrated. This kind of thing, repeated constantly, is how everything gets done in Yemen.

Dazed by what I’ve seen, I follow Ali blinking into the sun. For all the apparent chaos, the country has its efficiencies. There’s a tea counter immediately outside the restaurant, and within seconds of sitting down, we're enjoying a glass of sweet cardamom tea. It is extraordinarily bright. A woman wearing a shoebox on her head as a sunshade approaches us, asking for alms. I’ve noticed a lot of people by the side of the road with this kind of headgear.

A traffic jam has developed in front of the restaurant while we were eating. Trucks are stopped in both directions, and even the mopeds are having trouble getting through the tangle. The normal background of honking has fused into a continual wall of noise.

Ali looks at this and says “mushkila” (problem), which is about as animated as he gets about road hazards. I am curious to see how he deals with it. We climb into the Land Cruiser and his first bold move is to cross the traffic jam, cutting through both lanes and nosing us into a narrow gap between merchants’ stalls on the other side of the street. There he begins a twenty-point turn, turning the car gingerly in a tiny space and somehow merging in behind a giant truck. There we join the honking already in progress.

The truck in front of us turns off, revealing an ancient, angry man standing in the road ahead. He has a vast white beard and looks like one of the grumpier Old Testament prophets. In his hand he holds a long wooden staff. Threading his way between cars, the man singles out a stopped truck and starts beating on it as hard as he can with the staff, yelling the whole time. The truck honks in agony but can't move. As we inch closer, I can see that the old lunatic has a policeman’s coat draped over his shoulders. He's not a lunatic at all, but an official representative of the law, the only traffic cop I'll see in Yemen. The stick is the standard traffic management tool.

Two teenagers zoom past on a moped, going in the wrong direction, and nearly knock the cop off his feet. He curses at them but does not smite. His fury is reserved for the truck, which he continues to bang on, leaving dents in the door. The only traffic crime in this country is to stop moving.

Against all reason, the beating works. The shamed truck finds some tiny gap between two stalls and disappears into a roadside souq, and within minutes we’re back in motion, the honking back down to background levels, every car moving briskly between the speed bumps.

With the excitement over, it's time for us to enjoy the rich, smooth taste of qat. Because the active ingredients in qat degrade quickly, you have to buy it fresh every day. Day-old qat is still usable, but loses a lot of its kick. After two days, you're just buying expensive salad.

Ali gives me a helpful rule of thumb: If you see a big crowd of men, it’s always a qat market. If there aren’t many people, they’re selling bananas or vegetables. We spot a roadside souq that is teeming with men, and pull over. Most of them have already purchased their fix and are standing around, talking about it. Yemeni guys are worse than the pickiest coffee hipsters when it comes to qat. Not only do they obsess about the leaves, their price, their quality, and their provenance, but they are also picky about choosing the right companions and the right spot in which to spend their afternoon. Chewing the drug is a leisurely process that can fill five hours or longer, and the wrong set of buddies or chewing location can ruin the vibe.

This qat circus repeats itself every day, consuming vast amounts of time, energy, water, and fuel. Qat is a national disaster not because of its physical effects, which are mild, but because of the devastation it wreaks on the material and mental resources of the country. The drug economy dominates everything else in Yemen.

On this second day, I haven't learned enough about qat to hate it. I give Ali two thousand rials ($5) to score me a fix. The actual purchase takes about twenty minutes, and then Ali goes through an elaborate series of rituals to prepare the plant for chewing. He has a special mesh bag that he rinses the leaves in. If he can't find a pump or sink, he uses bottled water from the back seat. I'm grateful for this step, since qat is often drenched in pesticide. Once the leaves have been rinsed, he swings the bag around his head in a wide circle, like a centrifuge. The final step is hold the mesh bag carefully out the car window as we careen along at high speed.

The result is—well, it's still just qat. I notice the leaves are coarser and bigger here than what Fouad got me in Sana’a. I’m still not sold on this plant, but it pleases me to be able to keep pace with Ali, and let my mind spin as we drive.

And soon we are in Ibb.

We stop in the old part of the city, now on the periphery, to sightsee. The tower houses are as high as the ones in Sana’a, but noticeably different in style. There is less ornament and more rough stonework. Even the order of the floors is different, with kitchens up on the top floor rather than on the bottom. Once again, if it weren't for the electric cables and the lack of raw sewage, I could easily imagine myself back in the tenth century.

A guy in his forties stops me to say hello, and when he finds out I’m from Poland, he talks to me for a while in Russian. It turns out he’s a petroleum engineer who went to university in Russia, back when southern Yemen was a Marxist state. His Russian is excellent. He has very thick eyelashes and doesn't stop smiling for a moment as he speaks to me, which is kind of eerie. I see his teeth are heavily stained from qat.

At the end of our conversation, he switches back to English and asks me if I’m all alone. I misunderstand him and explain that I have family back home. But he is asking if I’ve arrived in Ibb by myself. He doesn't notice Ali, who is rummaging for something in the back of the car, a few dozen meters away.

“Be careful, my darling. If you are alone here. Take care.”

“Is there a problem?”

“No, take care. This is my advice.”

I press him but he won't say more. He's like a character in one of those video games where the innkeeper tells you something cryptic and then won’t elaborate. I shake his hand and run off to find Ali, like a lost lamb hastening to its mother.

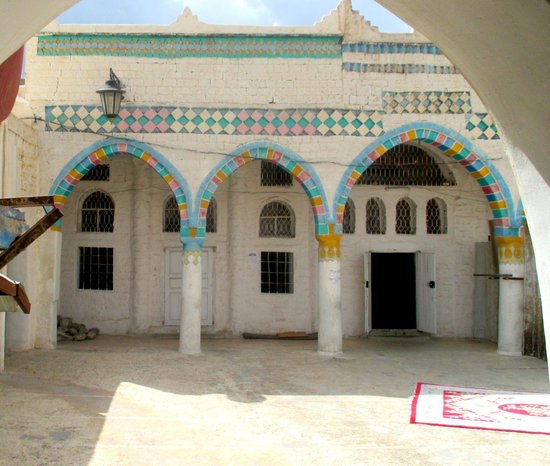

It’s hard to focus on the sights of old Ibb because a little phalanx of people has formed around me. It was clearly a slow day before I came along. Up ahead I can hear people relaying the word ‘tourist!’ and I see curious heads popping out of ancient buildings as I pass. A detachment of children follows at a discreet distance. One of the older kids is deputized to lead me into the Ottoman mosque, and the rest of the town goes back to what they were doing as we disappear through the thick gates.

The Ottoman presence in Yemen is interesting. The things they built—mosques and fortifications—reflect their main activities in Yemen, which were fending off attackers and praying to a merciful God to let them please go home. The Ottomans were brave soldiers, but they were also a conventional army stranded in an unforgiving landscape, fighting insurgent tribesmen who had nothing to lose.

Victoria Clark describes the Ottoman predicament in her wonderful short history of Yemen:

Still vivid folk memories of the last occasion they had ventured into the northern highlands plagued them. Recruits for their army in Yemen sometimes had to be chained and physically carried on board troop ships, so great was their dread of almost certain death in those desolate mountains. An old Ottoman folk-song captures the dismay and misery surrounding the very name of Yemen in the empire’s heartland:Yemen, your desert is made of sand

What did you want from my son?

I don’t know your way or your sign

I am just missing my son

O Yemen, damned Yemen!

Then as now, the northern Yemeni tribes liked nothing better than taking to the hills to fight off a foreign invader. The Zaidi hill tribes who still dominate northern Yemen are like a hive of angry hornets—endlessly annoying when you have to deal with them yourself, but wonderful to have on the rare occasions that an intruder trespasses on your property.

The constant prospect of violent death brought out a pious streak in the Ottoman armies, who channeled their fear into some very lovely mosques (with thick walls). So in one sense, everyone came out a winner.

Our last stop of the day is the old village of Jibla, relic of a fascinating period when Yemen was ruled by a woman. While notionally married to a dude, Queen Arwa ruled the country alone and is universally revered as one of Yemen's greatest spiritual and political leaders. There's even a sizable Ismaili community in India who still celebrates her, and makes annual pilgrimages to Yemen. Arwa is a figure a bit like Elizabeth in England; most of what you can say about her starts with the phrase “unusually for a woman…” She is a useful point of departure for anyone trying to get women in Yemen to be treated more like human beings.

One of Arwa's first acts as queen was to move the capital from restive Sana’a to the small town of Jibla, overlooking Ibb. As a result, the little village is stuffed to overflowing with mosques, and used to have a lively tourist industry. The drive up is extraordinarily scenic if you can overlook the massive modern prison that sits on a mountaintop just across the way.

Jibla looks great from a distance. Up close, I can see the buildings have been defaced with graffiti, and the little stream (!) that cuts through the middle of town has turned into an open-air dump. It’s full of ragged red plastic qat bags and general trash.

Ali hands me off to a melancholy guide named Yisa, a young guy in his twenties with a giant wad of qat in his cheek. Like every guide in Yemen, Yisa speaks five languages well, and learned them all on the job, back when the tourists still came.

Yisa is not too interested in small talk and takes me directly to Queen Arwa's mosque, the largest one in town. Like a lot of truly ancient mosques, the building is fairly plain-looking and heavily built. There's a red ochre tower that is five hundred years old, and a white tower that is almost a thousand years old. The mosque caretaker materializes, and after determining how big a donation I intend to give, makes a big deal about letting me through the door. You are the first non-Muslim ever to be let in the mosque!

Queen Arwa lies in a huge and gaudy tomb that fills one entire corner of the building. It smells fantastic. Somebody’s job is to spray the tomb with perfume every few hours, and they don't hold back. The tomb is a glorious confection of silver and gold with latticework windows that let you view the sarcophagus inside.

Outside, Yisa points out some of the dozens of other mosques. There used to be a couple reserved for use by women, but nowadays women are expected to just pray at home. Only Arwa is allowed to be in the mosque she built.

Everything in Jibla is ancient by my standards. The new stuff is six hundred years old, while the older buildings date back a millenium. I'm more interested in seeing the living village, but Yisa is intent on hitting his marks, and I dutifully photograph the ancient doorways, old inscriptions, and towers he points out to me.

The tour is supposed to last for an hour, but Yisa powers through in twenty minutes. The last half of our time together is spent in an unsubtle discussion of his circumstances. He is an orphan, and there are a lot of siblings depending on him. Perhaps I have noticed the large lump of qat in his cheek, he says. "I don’t normally chew qat. A friend gave this to me."

I don't care if he chews qat or not. Mostly I feel rotten that I can’t have a normal conversation with the guy; that there’s this abyss separating us and no way to cross it. He has his role to play, and I have mine.

The American tourist fantasy is to find a place that’s undiscovered and see a slice of "authentic" life (albeit with all the comforts and amenities of home); a place where the natives will be overjoyed to see you. They laugh and dance their native dances. You wander through the village, peering in to wave at the jolly baker, graciously accepting a flower from the shy but cute-as-button little kid who follows you around. An old man takes you aside to say something cryptic but profound, giving you his blessing. Songbirds alight on your shoulder but do not poop.

Jibla is certainly off the beaten track, but what's authentic here is hopelessness, hunger, and poverty. The townspeople don't care why I've parachuted into their lives from the First World, and in their place, I wouldn't care either. How can we can talk as equals when in ten days I will be back in San Francisco? Their job is to treat me with hospitality and extract whatever money they can, which can't possibly be enough to make any difference.

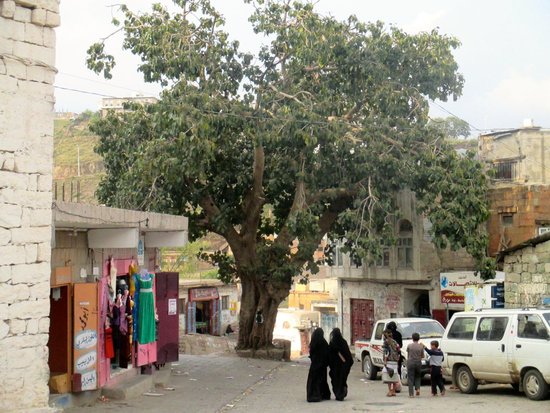

We end up under a huge ficus tree at the foot of the village. Ali has told me to meet him here at the end of the tour, but there's no sign of him or the car. I find his absence unsettling. Yisa insists that I come wait in his house and drink tea. I will be more comfortable there. It's rude to refuse this kind of direct invitation, but I do it anyway, as politely as I can. I don't trust my instincts much in Yemen, but they're all I have to work with. And my instincts are adamant that I remain outside, in public view.

It’s getting towards dusk, and we’ve run out of small talk. I feel exposed and baffled by Ali's long absence. Yisa keeps pressing me to come inside. A friend of his joins us to chat. Somehow, he also speaks excellent English.

Then, without warning, a little Chinese van roars up and bars the road downhill from us. A bunch of young men start climbing out the back. Almost at the same time, a Toyota pickup full of dudes comes down the road and stops a few meters uphill from where we're sitting, blocking the road there too. We’re boxed in. The young men beckon to Yisa and he goes over to talk to them, looking back at me from time to time. The situation takes on that unreal feeling you get when there's about to be violence.

But of course, nothing happens. My instincts really are useless. The minivan is the local bus service, and the pickup truck has come to meet it. The burly young guys disperse to their homes, and soon it's just the three of us again under the ficus tree.

Yisa asks me to promise that I’ll look for some kind of work for him. He’s trained as an engineer, but he will do anything, farm work, be a servant, cut lumber, wash dishes, it doesn’t matter. There is no future for him in Yemen. Do I understand that? I must promise not to forget his request.

I don’t have the heart to tell him that there’s no future for him anywhere I’m from, either. In the US, being from Yemen is practically synonymous with being a terrorist. The world expects people like him to stay put and suffer in place.

By the time Ali rolls in, I'm exhausted and ready to hide from the world for a while. The road back to Ibb takes us even closer to that large, ugly mountaintop prison.

Ali drops me at the hotel, and while he looks for parking I pop into the pharmacy next door to buy some shampoo and bottled water . I can't tell if it's the qat or the enormous lunch, but I've almost entirely lost my appetite. I’m gone for maybe five minutes, but when I step into the hotel, I see Ali and the desk clerk conversing heatedly. They are both relieved to see me.

“Enough. You’re in for the night now, yes?” says the hotel clerk. It doesn’t sound like a question.

① Of course Ali is not "Ali the driver", he has a last name, and it feels disrespectful to introduce him like I’m Tom Friedman interviewing my taxi driver. But on the remote chance that it might cause him trouble, I’m going to leave out Ali’s last name, and the last names of the other Yemeni people who showed me around.

② No footnote can do justice to the geopolitics of the Cola Wars. Very briefly, in the sixties, the Arab world attempted an economic embargo of Israel. Coca-Cola looked at the relative population figures and decided they were better off selling to Arabs, but public pressure in America soon forced them to start selling soda in Israel. This left an opening for Pepsi, which still dominates in the Arabian Penninsula (competing mostly against domestic brands). Coke is aggressively trying to get back in the game; on my last day in Sana’a I passed some vast, sponsored festival with Coca-Cola parade floats.

| « Sana'a | Ta'izz » |

brevity is for the weak

Greatest Hits

The Alameda-Weehawken Burrito TunnelThe story of America's most awesome infrastructure project.

Argentina on Two Steaks A Day

Eating the happiest cows in the world

Scott and Scurvy

Why did 19th century explorers forget the simple cure for scurvy?

No Evidence of Disease

A cancer story with an unfortunate complication.

Controlled Tango Into Terrain

Trying to learn how to dance in Argentina

Dabblers and Blowhards

Calling out Paul Graham for a silly essay about painting

Attacked By Thugs

Warsaw police hijinks

Dating Without Kundera

Practical alternatives to the Slavic Dave Matthews

A Rocket To Nowhere

A Space Shuttle rant

Best Practices For Time Travelers

The story of John Titor, visitor from the future

100 Years Of Turbulence

The Wright Brothers and the harmful effects of patent law

Every Damn Thing

Your Host

Maciej Cegłowski

maciej @ ceglowski.com

Threat

Please ask permission before reprinting full-text posts or I will crush you.