| « Seeking Testers For A Bookmarking Site | Localizing Pinboard » |

I arrived in Transnistria on the happiest day of the year - May 25, the last day of school. Packs of happy, singing students were wandering the streets, the boys dressed in suits or nice shirts and the girls wearing a kind of folk costume that combined apron, scrunchies, stockings and a disturbingly short UPS brown frock. Those lucky enough to be finishing eighth grade or high school also sported a big red sash. It was one of those cool and unsettled May days that can't decide between sun, rain, and clouds, and so tries each in turn. But the high school kids were in indestructibly good spirits, and every time a group from one school passed another there would be a volley of loud cheering. Everyone was headed to one of Tiraspol's big parks, to drink beer, text their friends, and enjoy the working attractions in the slowly disintegrating, Mad Max style amusement park.

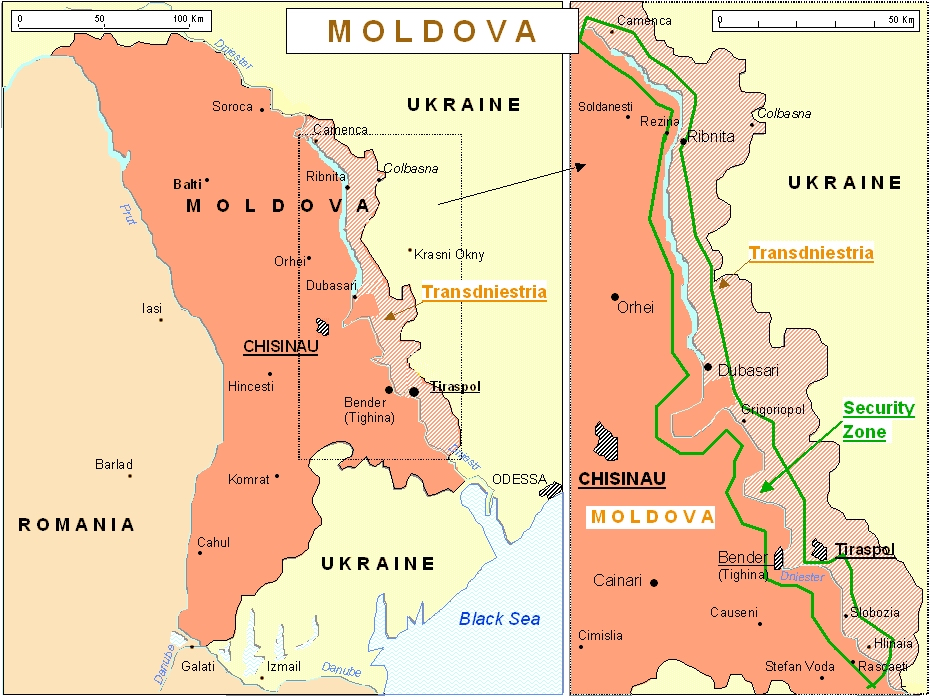

Transnistria is a long and skinny scrap of land along the Dniestr river, wedged between Moldova and Ukraine. In Soviet times, when an independent Moldova sounded about as likely as an independent Staten Island, the borders of the Moldavian SSR were drawn a little to the east of the Dniestr, the historical boundary of all things Moldavian. Over time, a large number of Russians relocated here, and the region grew into the Moldovan SSR's industrial heartland. When the Soviet Union began to fall apart in 1991, Moldova decided it wanted to secede, and the Transnistrians decided they wanted no part of it.

The Moldovans sent armed troops to help persuade the Transnistrians to change their mind, at which point the locally stationed Soviet 14th Guards Army volunteered its own opinion that it would probably be best for the Moldovans to go home. The 14th army's job, incidentally, was to oversee one of the largest conventional weapons depots in Europe, holding all of the ammunition and weaponry repatriated from East Germany and other parts of the disintegrating Warsaw Pact. The new Moldovan state found this line of argument very persuasive, and Transnistria has been a de facto independent state ever since.

There are a bunch of warnings online about visiting Transnistria, most of them having to do with shakedowns at the border. These warnings are hard to evaluate, as so much can depend on whom you encounter, where you cross, what kind of vibe you give off, whether someone is in a good or bad mood that day. The day of my crossing, an official film crew happened to be shooting footage of the border formalities, which certainly didn't hurt. It was the fastest and most convenient border crossing in the whole region.

Transnistria is not hard to get to. There are about a billion daily maxi-taxis making the forty-minute trip from Chișinău to Bender, and a smaller number that come from the Ukrainian side. Approaching the border, you first pass some unhappy Moldovan customs agents sitting in the middle of the road. Moldova refuses to build an actual checkpoint, since it considers Transnistria a breakaway province, but they also aren't thrilled with the idea of having a completely unmonitored eastern border. So agents sit in the road in lawn chairs and flag down the occasional truck.

Next up is a pair of concrete barriers designed to break the momentum of any advancing Moldovan armored columns long enough for the Russian garrison in Tiraspol to wake up and mount a defense. This is Transnistria's Fulda gap. Two chain-smoking Russian soldiers form the tip of the spear. Beyond them lies another hundred meters of straight asphalt and then the Transnistrian border checkpoint. There's a small metal trailer for passport control, a more permanent building for customs, and a big, ragged Transnistrian flag flying above it all, bleached pink from years of faithful service.

The guy sitting next to me on the maxi-taxi turns out to be an Austrian doing his dissertation on the political situation here. He's been living in Chișinău with a friend for the last three months, and this is his fourth trip into Tiraspol. He is full of interesting information about the place. Neither of the Austrians speaks Russian, but they claim they've never run into trouble at this border crossing. The border guards take us aside and deal with the locals on the maxi-taxi first.

The border crossing is completely routine. One guard complains that I didn't fill out my patronymic (Maciejevich?). His colleague eyes the Austrian passports and debates me for a while about the existence and interpretation of the letter ß. After the usual frenzy of stamping we receive our entry chits: I can stay in Transnistria until 21:40; the Austrians can spend the night. For all the bluster about independence, I'm surprised to find the guards lack the self-confidence to actually stamp the passports.

Soon we are in downtown Bender, passing another Russian checkpoint and riding over a pretty bridge (no photographs!) that spans the Dniester.

The president of Transnistria is a former apparatchik from Kamchatka named Viktor Voronin. His vaguely Colonel Sanders-like face dots numerous billboards across the territory. In some of them he is shaking hands with Medvedev; in others he is shaking hands with the leaders of South Ossettia and Abkhazia, under the somehwat plaintive slogan “let these countries exist!”. Like ostracized kids in a high school, the Transnistrians, South Ossettians and Abkhazians have grown tired of trying to get international recognition and instead banded together, sending delegations to one another and exchanging diplomatic visits in a kind of underground United Nations. In downtown Tiraspol you can even find a sort of embassy flying the very pretty Abkhazian flag.

On the way in to Tiraspol, the bus passes the towering, brand new soccer stadium. When it seceded, Transnistria took not just four fifths of Moldova's industrial base and 90% of its electrical production, but also the country's best soccer team. The new stadium is emblematic of the ambiguous relationship with Moldova, since even the Chișinău soccer team travels here to use it for important international matches. It's the only European class soccer stadium in the region. A five-star hotel is going up next to the stadium, and I spend some idle moments trying to imagine the kind of guest who would stay in a five star hotel and yet not mind the bone-rattling car ride from the nearest airport, in Chișinău.

The hotel, stadium and the adjacent gas station are owned by a conglomerate called Sherrif, Transnistria's answer to the RAMJAC corporation. Sherrif owns pretty much everything in the territory that doesn't already belong to the even shadier Russian gas giant Gazprom. Some bold analysts even whisper of Sherrif of having ties to senior figures in the Transnistrian government.

Further along the road sits the Russian army base, a little extraterritorial compound where a thousand or so Russian soldiers (the exact number is unclear) play cards and try not to go crazy with boredom. Since 1991, the Russians have been nagged into withdrawing or destroying most of the truly heavy weapons once kept here. Even so, dark rumors persist about Transnistria being a big player in underground arms traffic. The kind of smuggling for which there is actual evidence is far less glamorous, involving things like diverting shipments of Tyson chicken parts into Ukraine.

There really isn't anything exotic about Tiraspol apart from the weird geopolitical status. The city is mostly laid out along its main road, a clean and leafy boulevard called October 25 street. The road is anchored at one end by the university and the House of Soviets, and at the other by a large plaza with various monuments, including a large statue of Lenin. In between is an unremarkable selection of shops and cafes, along with local landmarks like the Kvint cognac outlet store (a wholly-owned subsidiary of the Sherrif corporation). Kvint has been making cognac for a hundred years, and bottles of the good stuff are one of the main attractions of visiting Transnistria.

Tiraspol has a large number of billboards, most of which carry nationalist propaganda. My visit comes hard on the heels of Victory Day, and so most of the posters are in celebration of victory in the “Great Patriotic War”, the Russian phrase for that portion of World War II in which they were not the aggressor. Other posters celebrate 18 years of Transnistrian independence, or else proclaim solidarity with the patron state (‘our future lies with Russia!’). To be honest, it isn't much different from the various exhortative posters one sees in the streets of Chișinău or Odessa, although those focus more on civic than national pride.

Travel accounts of Transnistria tend to obsess a little bit about the statue of Lenin in the main square. I've come across the phrases "living museum" and "a fly in Soviet amber", which to me suggest a certain lack of direct experience with advanced socialism. Magnavox outlet stores, for example, were not common in the Soviet Union. My favorite construction, though, comes from Leif Pettersen of Lonely Planet, who mentions the city's "Kafkaesque monuments", where he actually means "Orwellian"—a bit of autopilot prose that would have made Orwell beam.

So let's look at these Kafkaesque monuments! Within a few hundred feet of Vladimir Ilyich we find a large Orthodox church, a statue of a man transformed into a giant bug Catherine the Great, and a tank on a pedestal with the slogan "For the Motherland!" painted on its turret. Behind Lenin hangs a large banner reading "Our Future Lies with Russia!". And dominating the square is an equestrian statue of Suvorov, the legendary Russian general who founded this city in 1792. For an American analogue, imagine a big plaza with statues of Patton, Benjamin Franklin, Teddy Roosevelt, George Washington, a giant bald eagle, and triple-life-size Marines raising the flag at Iwo Jima.

What is on display here isn't nostalgia for Communism, but nostalgia for the Russian Empire, in both its tsarist and Soviet incarnations. The forms of Soviet iconography are respected because they represent a time when Russia (a nation with a massive inferiority complex) was a superpower, unquestioned leader to half the world, and undisputed victor over the Nazi empire.

Some of the visual language may be borrowed from Soviet times (partly because it's great visual language), but it's no coincidence that you never find a statue of Marx or Engels in one of these "living museums". The same kind of cognitive dissonance that lets Alabama rednecks wear a Confederate flag as a patriotic symbol obtains here. Vladimir Ilyich and Suvorov would not have found a lot to say to each other over sherry, but in Tiraspol they are happily celebrated as symbols of heritage. Their presence is a reminder of happier times, when Tiraspol was a new city in a dynamic and growing empire, rather than a the capital of a ridiculously shaped renegade province of the poorest country in Europe.

For some reason, Transnistria has a large and entertaining online presence, and a lot of it is in English. My personal favorite is the official tourist site ("Compared to Moldova, it's like the Riviera!"), which gamely confronts the challenge of luring tourists to a country with no recognized borders or airport, all while taking as many shots at Moldova as the format will allow. If you ever wondered what Charles Kinbote would sound like as an embittered Minister of Tourism, you will want to savor this piece of prose, possibly over a snifter of fine Kvint cognac.

Less otherworldly but equally entertaining is an outfit called the Tiraspol Times, which seems to be run by native speakers of English sympathetic to the Transnistrian cause.

Having sipped all the nectar I could from Tiraspol, I boarded a maxi-taxi back to Bender, with vague hopes of finding the recently-opened museum of the 1991 conflict. Instead I found myself wandering around a pleasant town, its streets marked both in Russian and in the mind-warping Cyrillic version of Romanian that still gets used here. Many people were out strolling and running errands. I discovered that Russian soldiers look far less intimidating when they are walking hand in hand with a two year old, sharing an ice cream cone. Bender was a normal, pleasant city, but it was a city curiously diminished. Everywhere were signs of how much things had fallen off in the past two decades—a disused central train station, an empty bus terminal now replaced by a small ticket kiosk, enormous and nearly empty factories the size of a city block.

Someone had left the door to that disused terminal propped open, and you could go in and admire the nice socialist realist mosaics and the outdated schedules. In Soviet times, this was a place you could easily leave. Odessa and Chișinău were a short ride away, further afield were Kiev and the Crimea, there was regular service to Moscow and other major cities. Europe was off limits, of course, but the USSR was a big place. Since then, people's horizons have narrowed. My mind wandered back to those happy graduates, and what kind of a future they could reasonably expect in this place, and more than ever I was annoyed with the uniforms, peaked caps, officious titles, stamps, checkpoints and other frippery of modern nationalism. I find it impossible to take the play-acting at countries and borders seriously, whether it's being done by Americans, Transnistrians, Molodvans, or Zemblans, but then I have the luxury of holding the right passports. For these kids, the asinine dispute over what to call this place and what flag to fly here will, unfortunately, have enormous consequences.

More photos here.

| « Seeking Testers For A Bookmarking Site | Localizing Pinboard » |

brevity is for the weak

Greatest Hits

The Alameda-Weehawken Burrito TunnelThe story of America's most awesome infrastructure project.

Argentina on Two Steaks A Day

Eating the happiest cows in the world

Scott and Scurvy

Why did 19th century explorers forget the simple cure for scurvy?

No Evidence of Disease

A cancer story with an unfortunate complication.

Controlled Tango Into Terrain

Trying to learn how to dance in Argentina

Dabblers and Blowhards

Calling out Paul Graham for a silly essay about painting

Attacked By Thugs

Warsaw police hijinks

Dating Without Kundera

Practical alternatives to the Slavic Dave Matthews

A Rocket To Nowhere

A Space Shuttle rant

Best Practices For Time Travelers

The story of John Titor, visitor from the future

100 Years Of Turbulence

The Wright Brothers and the harmful effects of patent law

Every Damn Thing

Your Host

Maciej Cegłowski

maciej @ ceglowski.com

Threat

Please ask permission before reprinting full-text posts or I will crush you.