| « Total Eclipse of the Sun | The Daintree Rain Forest » |

Because Captain Cook discovered the Great Barrier Reef the hard way, by running his ship onto it, the place names near his landfall tend a bit towards the emo. South of eponymous Cooktown are Mount Sorrow, Weary Bay, and a little east-facing bump called Cape Tribulation, so called because, as Cook wrote in his report of the 1777 voyage, ‘here began all our Troubles’.

For modern travelers, Cape Tribulation is likely to be the place all troubles end. The place is a postcard. As the northern terminus of the paved coastal road from Brisbane, the place has an air of romantic remoteness. Here the rain forest comes down nearly all the way to the water's edge, and only a crescent of beach, narrow or broad depending on the tide, separates the trees from the water. The coral sand is bright white, with only the occasional seafaring coconut from Polynesia as punctuation. The coconuts can't grow in this climate, but they're needed for atmosphere, and so central casting keeps sending them in across the Coral Sea.

The whole tableau is so lush and so over the top that you would roll your eyes at it if you saw it in a postcard rack. But Mother Nature is shameless, and in her hands the effect is magical. After a long drive through rain forest, the road ends at this magic stretch of beach, and the only thing you can think of is how fast you will be able to kick off your shoes and go dancing into the gentle waves.

But to go swimming here in November is unwise. If Cook had arrived at this time of year, his crew, in addition to being the first Europeans to see a kangaroo, might have discovered the box jellyfish. And then the place names would be things like 'Pain Cay', and the 'Bay of Screams'.

The box jellyfish is one of those Australian animals that are venomous beyond reason. It is a transparent creature about as big and as clever as a handbag, and although it subsists entirely on small fish and crustaceans, its three-meter long tentacles contain enough venom to kill an orchestra.①

The box jellyfish hunts by floating just off the beach and letting its tentacles drift in to the water's edge. The things that make northern Queensland beaches ideal for swimming—sandy beaches, constant sunshine, and the enormous breakwater of the Great Barrier Reef—also make it a paraside for the box jellyfish. Given that it is the most venomous creature in the sea, the total body count in Australia has been mercifully low, with sixty-four confirmed fatalities since 1883. Most victims in recent years have been children, whose smaller size means they need less tentacle contact to absorb a lethal dose. But even the slightest contact with the jellyfish produces a lifelong scar and a vicious sting (a common local name for it is the sea wasp). Despite the fierce summer sun, and the hundreds of miles of inviting beach, in three weeks in Queensland I will never see an unprotected person enter the water.

If you are being stung by a box jellyfish, and are of a philosophical bent, you can take comfort in knowing that the behavior is mindless. A jellyfish is a pretty decentralized thing, and its stinging tentacles are fully automated booby traps. Each one is covered with millions of microscopic structures called nematocysts, which are tiny poison harpoons rigged to fire when they brush against something that tastes like protein.② When triggered, the nematocysts fire with incredible speed, each little harpoon flipping inside out and leaving its casing with an acceleration of over five million G. Yet the structures are so rugged that you can reactivate a jellyfish tentacle that has dried in the sun just by getting it wet again.

People who get stung call the feeling memorable. Locals are careful to avoid the actual jellyfish; many of the stories you hear from them involve accidentally touching a fragment of tentacle that has broken off and drifted through a stinger net, or adhered to an anchor chain. It takes about two meters of tentacle contact for the sting to become life-threatening to an adult. At that point the pain must be indescribable, but it is at least brief. Jellyfish venom is the fastest-acting poison found in nature.

A friendly bus driver tells me the story of a local priest who dove headfirst into one of the things on a Port Douglas beach. “He was literally dead before his feet hit the water.” At most, the story exaggerates by two minutes, the scientifically attested time between initial sting and cardiac arrest. There is an antivenom available, but the only way it has been demonstrated to work is by pre-mixing it with the venom as it is administered. Until science perfects the anti-jellyfish, this antivenom will remain an expensive placebo.

Australians, being a hardy people, deal with the presence of the world's most dangerous marine animal with warning signs and vinegar. The vinegar helps deactivate any tentacles clinging to your skin so you can remove them without doing yourself more damage. The warning sign shows a picture of a swimmer in briefs being attacked by something out of H.P. Lovecraft, and cautions that ‘marine stingers are present in these waters during the summer months’. The committee in charge of creating the signs presumably considered adding words like "danger" or "no swimming", but found them over the top. They try not to coddle you in Australia.③

'Marine stingers' is the local blanket term for several species of these awful things, which biologists call the cubozoa. The box jellyfish proper (chironex fleckeri) has a family of little peanut-sized relatives called irukandji. Despite their tiny size, these tiny jellyfish can still unfurl about a meter of spider-web-like tentacles. Unlike the box jelly, irukandji have a mild sting, so you may not even notice one has touched you until the delayed side effects set in about half an hour later. At that point, however, you will most certainly notice, as will anyone close enough to hear the screaming. The jellyfish scientist Lisa Gershwin describes irukandji syndrome like this:

It gives you incredible lower back pain that you would think of as similar to an electric drill drilling into your back. It gives you relentless nausea and vomiting. How does vomiting every minute to two minutes for up to 12 hours sound? Incredible. It gives waves of full body cramps, profuse sweating...the nurses have to wring out the bed sheets every 15 minutes. It gives you very great difficulty in breathing where you just feel like you can't catch your breath. It gives you this weird muscular restlessness so you can't stop moving but every time you move it hurts. It gives you a feeling of impending doom. Incredible. Patients believe they're going to die and they're so certain of it that they'll actually beg their doctors to kill them just to get it over with. And all of this from this little tiny jellyfish.

The irukandji poses a special problem for scuba divers, because the symptoms of irukandji syndrome are hard to distinguish from acute decompression sickness. Failing to notice the sting can add an incredibly expensive visit to a hyperbaric chamber to your already dismal day.

What is truly scary about the marine stingers is how little we still know about them. In 2007 an American tourist, Robert King, wrapped up his Australian vacation by discovering a completely new species of irukandji jellyfish, which the Australians graciously (and posthumously) named malo kingi in his honor. In the process, he disproved the conventional wisdom that irukandji syndrome is not life-threatening to healthy people.

The idea that, in 2007, a man could go to a popular vacation resort and be killed by a jellyfish unknown to science is not one that sends you skipping into the Coral Sea. But although these animals are ubiquitous, we know almost nothing about them. The life cycle of the irukandji jellyfish in particular is a total mystery. They occur worldwide, but no one knows where they spawn, what they look like in their juvenile form, or what role they play in the ecosystem. And no one has any idea how the venom works.

The box jellyfish, despite being much larger, poses similar problems. The sessile form of the box jellyfish—its alter ego for half the year—has been found in nature only once, back in 1985. Even such elementary questions like how well it can see (it has twenty-four eyes) or what provokes it to move from feeding site to feeding site remain unanswered. Just last year, researchers discovered that one species of the cursed things can actually navigate, using an upward-pointing eye to detect when it has strayed too far from its feeding grounds under mangrove trees. How an animal with no brain coordinates such sophisticated behavior is—wait for it—a mystery.

The most pressing question about these weaponized jellyfish is what effect sea warming will have on their distribution. Northern Queenslanders have learned to live with their beaches shut down for half the year, but you can imagine the effect a vigorous population of irukandji (which are found worldwide) would have on tourism in Florida.

One of the few things we do know is that mangrove swamps like the one at Cape Tribulation are where the box jelly spends its childhood. Here it lives as a tiny polyp on the underside of rocks, zapping brine shrimp and other tiny animals, until some unknown stimulus makes it assume its adult medusa form. When it grows big enough to start catching fish, its venom changes composition to better attack vertebrates, and (from our point of view) becomes much more potent. Sometime in October or November, the summer rains wash the jellyfish out of the swamps (or do they migrate? No one knows), and so ends another year's swimming season.

Flooding right out with them is another excellent reason to stay out of the water, the saltwater crocodile. Crocodiles are numerous in northern Queensland and all through northern Australia and New Guinea. They prefer a quiet life in estuaries and rivers, but as their name implies they can do a limited amount of swimming out in the ocean, usually to commute home after a particularly vigorous monsoon. They have also been found to drift surprising distances on ocean currents, using them like sailors to move hundreds of kilometers with minimal effort.

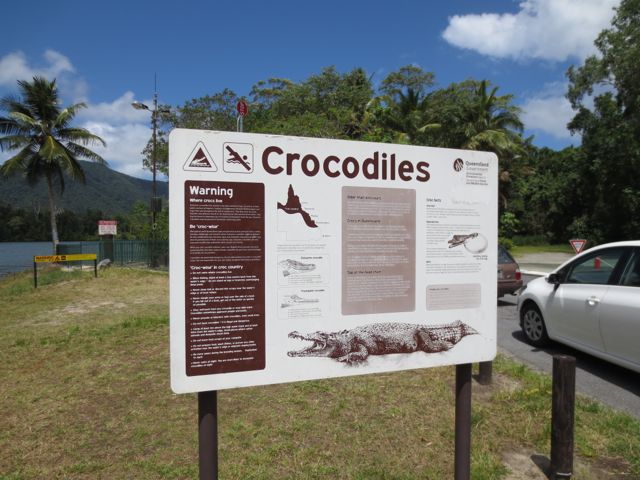

It's not common to spot a crocodile during the daytime, but you can sometimes see their landing places on the river banks. They are scary in direct proportion to how much you learn about them; I calibrate my fear by the fact that the same Australian authorities who found no need to add "no swimming" to marine stinger signs have written WARNING in large red capital letters on the crocodile signs by the river.

The salt-water croc is furtive but not shy, and right where the water becomes too fresh for the jellyfish is where you need to worry most about the crocodiles. There are big billboards warning about them at the entrance to the Daintree river ferry, but to me the best preventative is a visit to the crocodile enclosure at the Port Douglas wildlife park. The giant animals lie motionless in the sun, but very rarely one will move, and when it does it goes like lightning.

Visitors' guides stress the importance of “crocodile safety” in the same gentle language they use to warn against sunstroke. The universal theme in crocodile attack stories is that of complete surprise, the victim usually disappearing under the water before they can get out one good yell. The crocodile prefers to store its supper to age a little bit before eating, so the aftermath of many crocodile attacks is a grisly hunt for both the reptile and the cached body.

In a better world, box jellyfish and crocodile would be mortal enemies, battling each other out in the shallows like the kraken and the whale, but as best I can tell the creatures coexist in the tidal zone in perfect friendship and harmony, possibly buying each other beers after a hard day's work of making it impossible for a hot and weary traveler to put so much as a toe in the water.

① Since orchestras and box jellyfish both vary considerably in size, it's hard to make the claim unequivocal. Attention to tentacle placement, and the appropriate selection of larger cnidrians, would presumably play a key role. The universally cited figure is that one box jellyfish has enough venom to kill sixty people, but I suspect this is an estimate based on the jellyfish having sixty tentacles. At the limit, big orchestras like the Cleveland Symphony (100 members) might require two individuals, and it could take as many as six to dispatch the Mormon Tabernacle Choir (360). But in this era of budget cuts and shrinking audiences, you can be confident that one chironex fleckeri will have a powerful effect on the evening's programme almost anywhere.

② Many lifeguards in Australia pull nylon stockings over their limbs and torso as a cheap form of jellyfish protection, as nylon does not trigger the chemical receptors on the nematocyst. Lycra 'stinger suits' work on the same principle.

③ And they lack the resources to coddle! In researching anything about Australia, you are liable to come across an arresting reminder of just how big and empty the country is. For example: ”The Northern Territory has a coastline of 10 950 km, and the Royal Darwin Hospital (RDH) is the 300-bed referral hospital servicing the region."

| « Total Eclipse of the Sun | The Daintree Rain Forest » |

brevity is for the weak

Greatest Hits

The Alameda-Weehawken Burrito TunnelThe story of America's most awesome infrastructure project.

Argentina on Two Steaks A Day

Eating the happiest cows in the world

Scott and Scurvy

Why did 19th century explorers forget the simple cure for scurvy?

No Evidence of Disease

A cancer story with an unfortunate complication.

Controlled Tango Into Terrain

Trying to learn how to dance in Argentina

Dabblers and Blowhards

Calling out Paul Graham for a silly essay about painting

Attacked By Thugs

Warsaw police hijinks

Dating Without Kundera

Practical alternatives to the Slavic Dave Matthews

A Rocket To Nowhere

A Space Shuttle rant

Best Practices For Time Travelers

The story of John Titor, visitor from the future

100 Years Of Turbulence

The Wright Brothers and the harmful effects of patent law

Every Damn Thing

Your Host

Maciej Cegłowski

maciej @ ceglowski.com

Threat

Please ask permission before reprinting full-text posts or I will crush you.