| « Cape Tribulation | Pursuing The Platypus » |

The cassowary is a two-meter high bird with a large horn on its head, cankles, a red wattle, and a bright blue neck. The fact that it is well-camouflaged in the Australian rain forest tells you something about this remarkable habitat.

Every so often a nature show tries to bill the cassowary as ‘the most dangerous bird in the world’, and even though this is technically true, it's a little disingenuous. Northern Queensland makes a lot of competing demands on your fear. From old classics like the paralysis tick, salt-water crocodile, and box jellyfish, to hungry young newcomers like the the flesh-eating Daintree ulcer, the Daintree rainforest has a deep bench. And even though the cassowary has giant slashing blades on its feet, and is powerful enough to disembowel a person with one kick, it's clear that the bird's heart is not in it. It just wants to eat fruit and be left alone. There are plants in Daintree (read on!) scarier than the cassowary.

Most mornings in Port Douglas I go down to the wildlife center to watch Cassie the cassowary eat her breakfast, a large bowl of fruit that has been laid out for her by the volunteer staff. She stands above it with quiet dignity, dipping her head occasionally to grab another piece. There are two cassowaries at the center, both left free to roam in the semi-open enclosure. Cassie prefers to stand by the door, while Ayerlie likes to hang out under the raised walkway, startling passers-by by poking her head out near their feet. The cassowary has an unnerving stare. Like its relative the emu, it fixes you with giant, unblinking eyes (framed by gorgeous lashes!) with an intensity that makes you wonder if it is having second thoughts about a fruit-only diet.

Cassie is less interested in passers-by, perhaps because of her high-profile station near the entrance. It's amusing to watch visitors react as they come out the screen door and see the enormous, blue-necked creature grooming its long black feathers just a few steps away. The cassowary's feathers are so long and fine they look almost like fur. Once in a long while, Cassie lets out a seismic, almost inaudibly low growl that sounds like a fair-sized motorcycle gang revving up just over the horizon. You feel it more in your chest than hear it. This is the bird's territorial call, and the casque on her head serves as an amplifier, making it easier for it to her to hear the same low frequencies at a distance ①. Infrasound penetrates the thick forest much more easily than sounds of a higher pitch. The growling completed, she settles down carefully, folding her legs under her, and rests for a while on the ground like a giant hen.

Being mobile and solitary, the cassowary has a hard time adjusting to the modern human presence in Australia. For the last three centuries, non-indigeneous Australians have been hypnotized by the idea that, with enough spadework, this fascinating continent could be made to look like Dorset. The result everywhere has been catastrophic, but it is especially pitiful here. One of the richest habitats in the world has been cleared to make way for vast fields of sugar cane ②. More recently the Queensland authorities have designated ‘cassowary corridors’, or links between remaining patches of rain forest, to allow the birds to wander. It takes quite a bit of territory to satisfy a cassowary, and even more territory to give it a chance at finding a suitable mate. To get from one patch of forest to another means crossing busy roads, and the biggest threat to the southern cassowary (which has no predators) is the automobile. Speed bumps and cassowary crossing signs don't deter visitors from barreling along rain forest roads at high speed.

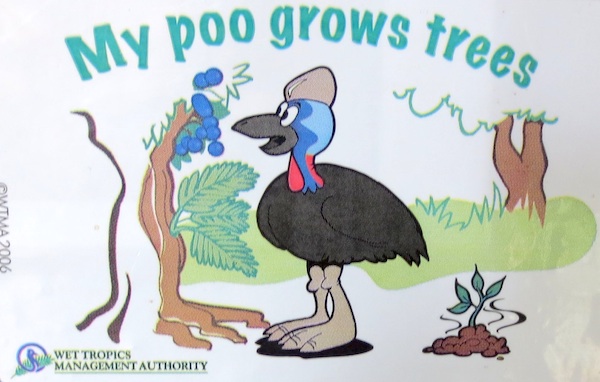

To the cassowary, the Daintree rain forest is a big, year-round buffet. Like coffee hipsters who won’t touch beans that have not first passed through a civet cat, some plants in Daintree won't even germinate until their seeds have transited a cassowary. The bird's nitrogen-rich turds give seedlings a huge advantage in the race for the canopy, and like doting parents frantic to get their children into Harvard, plants will go to great trouble to get their fruit into a cassowary. The itinerant and hungry bird is happy to oblige, eating its fill under a variety of trees that have specialized in making it happy, then walking several kilometers until it's timefor another feast. It deposits new generations of fruit trees as it goes. The cassowary eats, the plants grow, and both sides of the arrangement are happy. ③

This struggle for canopy is a feature of any forest, but it is unusually murderous in the tropics, where water and sunshine are abundant and there is no winter break. The first task of any seedling is to break through into sunlight, and plants will resort to desperate measures, including climbing all over their rivals until one or the other collapses under the weight. The rain forest only looks peaceful because we see it at a human time scale, and fail to notice the slow-motion deathmatch.

Given the effort they expend to attract cassowaries, plants look dimly on any third parties that try to crash the fruit party, especially third parties who can't be trusted to pass the seeds whole. Unfortunately for us, they solve this free-rider problem with poison. Despite the enormous diversity in species, and the abundance of fruit, there is almost nothing safe in the forest for people to eat. Through what one imagines to have been a miserable series of experiments, the aborigines have worked out protocols for how to eat some of this stuff without dying. There is a nut, for example, that if you cut it into thin wafers, wrap them in a cloth, leave the bundle suspended in a stream for three days to leach out the poison, pound it into a mash, and take care not to eat more than a small fingerful at one sitting (so you don't go blind), is edible. These are the snack options available in Daintree.

The rain forest finds other ways to be unwelcoming. The first plants to grow after a space has been cleared tend to be particularly awful, which means footpaths and sunny clearings are some of the more hazardous places to walk in the forest. My favorite of these pioneers is the vegetable kingdom’s shout-out to the nearby box jellyfish, a plant the normally unflappable Australians have named the ‘stinging tree’. Nomen omen. The stinging tree is covered in a myriad of tiny glass spines that embed themselves in your skin at the slightest touch. And because we are talking about Australia, the glass is coated in neurotoxin. The wound will keep hurting for weeks, and then it will start to itch.

My Aussie friend describes leaning against such a tree trunk with his hand to catch his balance, realizing only too late that it was an oversize stinging tree. It was a week before he could touch anything, and two months before his hand finally felt normal. The first night he spent an interesting evening with tweezers and a bottle of whisky. The recommended treatment, he learned later, is a depilatory wax strip. Given the amount of pain involved, it's fortunate that he didn't have access to a machete.

The stinging tree is not without a sense of humor. Its bright red fruit, if you can think of a way to remove the neurotoxic peach fuzz, is one of the few edible fruits in the forest.

Another way to pass some time in the sunny parts of Daintree is by hooking yourself on the lawyer vine, or wait-a-while. These beautiful names give you a sense of just how many thorns cover this aggressive, creeping vine. It catches on absolutely everything and uses its powers of attachment to climb up other plants (a standard strategy in the rain forest) towards the canopy, eventually crushing them under its own weight. Up close it looks a lot like a burr, if you have ever seen a burr dozens of meters long and as thick as a banana.

The final joke the Daintree rain forest plays on people isn’t obvious to the casual visitor, but catches many hikers unaware. Despite the name, it can be difficult to find fresh water when it’s not actively raining. And when it does start to rain, it rains torrentially, and you are liable to find your legs covered in leeches. Daintree takes its rain seasonally, during the period from December to April known as the ‘Big Wet’, and at other times hikers struggling up the Mount Sorrow trail have found themselves stranded in the dark, miserable and dessicated, surrounded by poisonous fruit and loud, mocking birds.

Until recently, a cassowary named Elvis guarded the approach to Mount Sorrow like some kind of bridge troll, preventing many people from even attempting the hike. This uncompromising bird patrolled the beach at the trailhead, holding one couple hostage for forty minutes, and on another occasion surprising an Indian tourist with a kick from behind as he photographed a sunset. The Port Douglas gazette reports, with a straight face, that the poor man “ran into the safety of the water”. His further fate is not recorded.

Elvis was eventually trapped and deported to some more remote part of Daintree, exiled for the crime of taking the fight too aggressively to The Man. The forest has been further defanged in a couple of places where biologists have set up ground-level boardwalks and elevated walkways that take you through the canopy. The view from these is spectacular. Very little of what goes on in this forest is visible from ground level, and the catwalks give a sense of just how specialized every plant and animal becomes in such a rich habitat. The view from up high, along with explanatory placards, also tips you off to the Daintree's big secret.

It turns out that this is one of the oldest ecosystems on the planet. I remember marveling when I visited Poland's last stretch of primeval forest that the patch had existed uninterrupted since the glaciers retreated from Central Europe 12,000 years ago. But the Daintree rain forest has been around for 180 million years, about ten thousand times as long. Before there was an Australia, before there were flowering plants, or cassowaries to eat their fruit, this forest was already growing. Through a fluke of geology and climate it has persisted all the way into our era, along with a selection of giant ferns and other relic plants found in no other part of the world. It is humbling to be in a place that predates not only your species, but your genus, family, and order, and remembers your class when they were just a bunch of scurrying, trembling little dinosaur treats. Given its incredible antiquity, it doesn't seem fair that we should now have the power to decide this forest's fate, but here we are.

① There is controversy over the cassowary's casque. The leading theories are that it is a simple case of sexual selection (like the peacock's tail) with no practical function, that it is a kind of crash helmet to protect the bird as it runs head-down through the forest, that it protects the bird's head from falling fruit, or that the cassowary uses the casque to dig through leaf litter. With great tact, the biologist Andrew Mack has pointed out that cassowaries do not run with their heads down, and that they invariably use their feet, rather than their heads, to rake through leaf litter. He implies but does not say outright that some of his fellow theorists might benefit by spending, say, ten minutes watching an actual cassowary rather than Road Runner cartoons. Mack does not exclude the possibility that the casque is just a sexual ornament, but he finds the fact that it is ideally structured to amplify sound at low frequencies, and connected to the bird's inner ears, provocative.

② Farmers and fishermen in Australia test the limits of human empathy. While I was in Cairns, for example, controversy ranged around the recent extension of the Great Barrier Reef marine park, opponents arguing that the expanded ban on fishing would harm the Cairns fishing industry, and proponents arguing that that was the whole goddamn point. If it were up to Australian farmers and fishermen, the Great Barrier Reef would be processed into bags of fish meal, the fish meal spread as fertilizer on land obtained by clearing the remaining rainforest, the fertilized land used to grow sugar, and the sugar used as raw material for some of the least appetizing desserts in the world. The fundamental question is this: do we prefer our biomass in the form of gorgeous reef and rain forest ecosystems, or Australians? Unfortunately, the only country that has any say in the matter is also the only one that finds the question hard to answer.

③ This approach to spreading seeds by making tasty fruit for large animals to swallow whole is very common (the technical name for it is megafaunal dispersal syndrome). It worked wonderfully until human beings began to spread out of Africa, hunting large animals on every other continent into extinction. And so we live in a world full of fruits—avocado, mango, papaya, honey locust, osage orange, gingko—whose seeds are designed to be pooped out by large animals, but who have been left without their animal partner. In this respect, the trees of northern Queensland are lucky to still have the cassowary. See The Ghosts of Evolution for the full, fascinating story.

| « Cape Tribulation | Pursuing The Platypus » |

brevity is for the weak

Greatest Hits

The Alameda-Weehawken Burrito TunnelThe story of America's most awesome infrastructure project.

Argentina on Two Steaks A Day

Eating the happiest cows in the world

Scott and Scurvy

Why did 19th century explorers forget the simple cure for scurvy?

No Evidence of Disease

A cancer story with an unfortunate complication.

Controlled Tango Into Terrain

Trying to learn how to dance in Argentina

Dabblers and Blowhards

Calling out Paul Graham for a silly essay about painting

Attacked By Thugs

Warsaw police hijinks

Dating Without Kundera

Practical alternatives to the Slavic Dave Matthews

A Rocket To Nowhere

A Space Shuttle rant

Best Practices For Time Travelers

The story of John Titor, visitor from the future

100 Years Of Turbulence

The Wright Brothers and the harmful effects of patent law

Every Damn Thing

Your Host

Maciej Cegłowski

maciej @ ceglowski.com

Threat

Please ask permission before reprinting full-text posts or I will crush you.