| « Microsoft's Hypocrisy on DACA | Who Should Secure Congressional Campaigns? » |

The Stranding of the MV Shokalskiy

Australians have an odd relationship with Antarctica. The fact that there's an even less hospitable piece of territory further to the south seems to soothe the young country, reassuring them that the attempt to re-create rural England on a vast slab of desert using convict labor wasn’t a mistake.

Douglas Mawson, the Antarctic national hero, is a wooden but stoical fellow who claimed a vast wedge of Antarctica for the British Empire at the start of the 20th century, back when claiming things for Britain was the most patriotic thing an Australian could do. (The Empire thanked him politely and gave it back.)

While Australia’s claim to sovereignty is in abeyance under the Antarctic Treaty, the fondness for Mawson, and a sense of proprietary ownership over the far south, lingers.

Mawson’s grandly named Australasian Antarctic Expedition left Hobart in 1911, arriving at an outcrop called Cape Denison almost due south of Tasmania in late December. Attracted by a bare patch of earth, Mawson accidentally picked the windiest place on the planet—averaging 284 days a year of strong gales—to build his base camp, a collection of wooden huts.

Once the short party had set up the huts, Mawson headed east to explore with two companions, Ninnis and Mertz. Some 500 km east of their camp, Ninnis dropped into a crevasse, along with the best dog team and most of the party’s supplies. Mertz and Mawson turned back in a harrowing race for survival, eating their sled dogs along the way.

We had breakfast off Ginger’s skull and brain. I can never forget the occasion. As there was nothing available to divide it, the skull was boiled whole. Then the right and left halves were drawn for by the old and well-established sledging practice of “shut-eye,” after which we took it in turns eating to the middle line, passing the skull from one to the other. The brain was afterwards scooped out with a wooden spoon.On sledging journeys it is usual to apportion all food-stuffs in as nearly even halves as possible. Then one man turns away and another, pointing to a heap, asks “Whose?” The reply from the one not looking is “Yours” or “Mine” as the case may be. Thus an impartial and satisfactory division of the rations is made.

On their return journey, Mertz and Mawson both consumed dangerous quantities of dog liver.➀ Mertz, the vegetarian, suffered more from the starvation diet, alternating between lethargy and fits of rage until he at last fell into a coma and died. Mawson kept going, covering the last 100 miles by himself. Whether or not he snacked on Mertz is a polarizing question in Mawson scholarship.

At one point on the return journey, Mawson fell through a snow bridge and found himself dangling by his sled harness over a void. The exhausted explorer had to pull himself up along fourteen feet of frozen rope, one knot at a time. When he reached the lip of the crevasse, it gave way, precipitating him down the full length of his harness again.

With his fingers numb and clothes full of snow, he managed the climb a second time, and lay motionless on the edge for an hour before finding the strength to get up. After that, he made himself a kind of rope ladder, and while subsequent falls never became a highlight of his day, they at least grew somewhat less lethal.

Frozen and starving, Mawson walked west. One afternoon he saw a dark spot on the ice and discovered a cairn and bag of food left for him by a search party. A note revealed that his companions had left it only hours before. They were no more than five miles away, but in his weakened condition, he had no hope of catching up.

The food at this cache gave Mawson the strength to make for a larger depot called Aladdin’s Cave, a proper shelter in the ice just five miles from the huts. Among other wonders, this cave contained three oranges and a pineapple, brought out from the ship that had come to take him home.

But Fate wasn’t done kicking Mawson in the nuts jut yet. Almost within sight of Cape Denison and the ship, Mawson was stopped by a week-long blizzard. When he finally staggered into camp, all that remained of the relief vessel was a smudge of smoke on the horizon. He had missed being rescued by hours. He spent the winter exchanging wireless messages with his fiancée, the arrestingly named Paquita Delprat, and hanging around the other men, not wanting to be alone. His memoir, with the unfortunately Dairy Queenish title Home of the Blizzard, is a classic of the Antarctic literature.

Mawson’s experience distills the Victorian age of Antarctic exploration to its essence, combining an unbelievable personal fortitude with the overall pointlessness of the endeavor. Even by Antarctic standards, George V Land was unexciting. The best thing you can say about it today is that sometimes a meteorite lands there.

But Mawson left behind a hut, and by the iron laws of Antarctic nostalgia that apply to any human structure below the 70th parallel, that hut is now an object of veneration, and must be visited.

A member of the AAE in 1911 picking ice in 100-mph winds

In 2011, the Australian climate scientist Chris Turney heard the call of the Antarctic. As readers of this blog know, that can be an expensive call to hear. But the approaching centenary of Mawson's expedition gave Turney a unique fundraising hook.

Turney teamed up with fellow scientist Chris Fogwill to announce a 2013 repeat of the Australasian Antarctic Expedition. They would adopt the same name, return to Cape Denison and (this part was kept a bit hand-wavy) complete Mawson’s important scientific work.

For their ship, Turney and Fogwill turned to the struggling Far Eastern Hydrometeorological Research Institute in Vladivostok, which was willing to charter the ice-hardened vessel Akademik Shokalskiy, complete with expert Russian crew, for $31,000 a day.

The organizers also enlisted the help of mountaineering legend and Antarctic explorer Greg Mortimer to provide adult supervision and serve as the liaison to the Russian crew. Significantly, neither Mortimer nor anyone else on the expedition team spoke Russian, while I would describe Captain Igor Kiselev's English as highly nautical.

Unable to get financial backing from the Royal Geographical Society, Turney found a patron in Google Australia, who agreed to become a keystone sponsor if Turney would post Google Hangouts from the ice and in other ways promote the Google+ platform. Turney agreed to raffle off two spots on the subantarctic leg of the voyage to schoolteachers who entered the Doodle4Google competition.

To make up the rest of the money, Turney offered twenty-six berths to paying tourists who were willing to serve as support staff for the scientific personnel, an arrangement that has a long pedigree in Antarctic exploration. To give the project more publicity, he invited along two Guardian journalists and a reporter for the BBC world service. In exchange, the Guardian set up a custom page for the expedition.

All told, the passengers heading to Antarctica comprised 49 expedition members, a Russian crew of 22, and Turney’s wife and two young children. On December 9, the ship sailed from New Zealand for Cape Denison.

Here we must introduce another key player in this story, Iceberg B-9.

Iceberg B-9 began its existence as an undistinguished part of the Ross Ice Shelf. Very little is know about its early life until 1956, when the U.S. Navy landed and carved a settlement called Little America V into its surface. It’s hard to say how this transformative moment affected the ice sheet's outlook. All we know is that in 1987, a Bali-sized piece of ice called B-9 broke entirely off the ice shelf, taking the ruins of Little America with it. The iceberg spent a year meandering northwest, rounded Cape Adare, and then melodramatically broke into pieces.

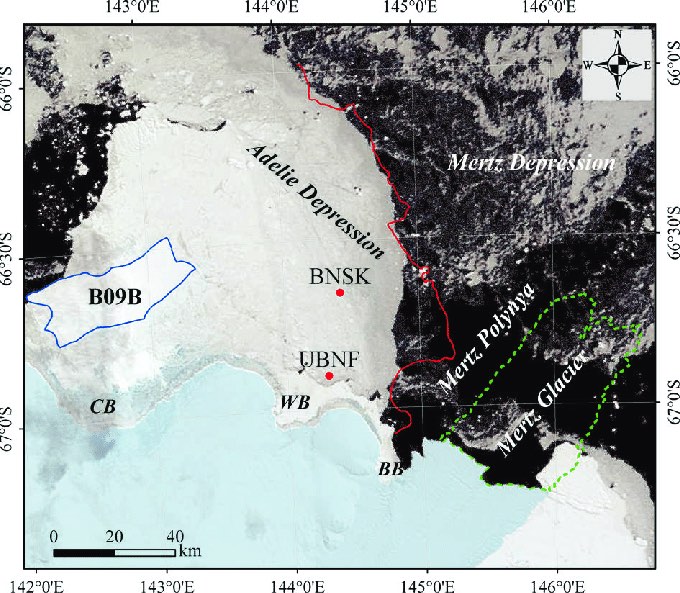

One of these fragments, now renamed Iceberg B-09-B, drifted further west, clipping off the tongue of the poor Mertz Glacier in East Antarctica in 2010 before settling in Commonwealth Bay, just to the north of Mawson’s huts. And there it remained, clogging the normally ice-free bay with trapped sea ice and making life a misery for the Adélie penguin colony, who now had to commute ten miles to reach breeding grounds that were once right on the water.

This 70-mile-long slab of ice had thwarted every attempt to celebrate the Mawson centennial, making Cape Denison inaccessible by sea. Like in a fairy tale, three ships had set out, and three ships came back, each defeated by the fast ice that had accumulated around the berg.

But Turney had a plan.

The revamped Australasian Antarctic Expedition would carry Argos, small all-terrain vehicles that look like what they are—little boats with wheels. The Argos can handle difficult terrain, and they float. Because sea ice is notoriously untrustworthy—even concentrations of it many meters thick have broken out in midwinter without warning—having a vehicle that becomes a boat in water was a necessity for what would be the longest sea ice crossing ever attempted.

The Shokalskiy reached the fast ice (the layer of sea ice that is attached to land, like a skirt) north of Cape Denison on December 17. The weather was mild, and Turney’s team spent a couple of days counting leopard seals and scouting a path around the cracks and pressure ridges that surrounded B-09-B.

On December 19, they made their first attempt to reach the huts, hugging the shore to escape the worst of the pressure. It took the two Argos five and a half hours cross the 70 kilometers to Mawson’s huts, which they found partially filled with snow. Each party of three carried two weeks' worth of supplies in case they got stranded, but conditions were unexpectedly benign. In a spot famous for its bad weather, the sun was shining, there was not a breath of wind, and it got so warm that people had to work in their shirtsleeves.

Turney helped the two volunteers from the Mawson’s Huts foundation dig out some ice and snow, and retrieved a life-size fiberglass dog that is a totem for Australian scientific staff, who make a game of stealing it from one another. Leaving the volunteers to work overnight, the rest of the team headed back to the ship, crossing a river of meltwater on the way.

All the passengers were eager to visit Mawson’s huts, the highlight of the expedition. But the hours-long journey over ice in a vehicle with no suspension was torture. A single passenger was chosen by lot to go out with the second group of scientists. Together with one of the Guardian journalists, they set out on a second trip to retrieve the volunteers who had spent the night.

The forecast for the next two days called for the weather to deteriorate, and Turney had a decision to make. If he kept the ship on station, it might not be possible for anyone to visit the huts again. The ship’s company, who had each paid thousands of dollars for their berth, would then return to Australia without ever having set foot on land.

Even if the weather cleared, the trip was hazardous. Many of the passengers were elderly, and at least one had limited mobility. The intense katabatic winds that Cape Denison is famous for could spring up without warning. There was no safe way to send a party of retired winemakers 70 kilometers from the ship in difficult ice conditions.

Turney chose another option. He would ask the captain to sail a long clockwise loop around Iceberg B-09-B to a point near the Hodgeman Islands. These rocky outcrops held no special scientific value, but they counted as part of the mainland, and landing there would give the passengers an opportunity to make an Antarctic landfall. The detour would also help Turney keep his promise to the journalists, who had been told they’d be given significant time on the Antarctic continent.

On December 22, the ship began a 30 hour detour to the Hodgeman islands.

The change in venue made the experienced sailors on the ship uneasy. In Commonwealth Bay, the ship had had the open ocean at its back. Any sudden rise in the wind would tend to push it out to sea. At the Hodgemans, the ship would be confined to a narrow channel betweeh two areas of fast ice, where both the prevailing winds and sea currents would tend to push it away from safety, and bring more sea ice into its path.

The Berserk

The way rescue works in the Southern Ocean is simple. Any available ship stops what it is doing and goes to help.

In 2011, the Shokalskiy’s sister ship, the Professor Khromov, was in the Ross Sea when news arrived that a yacht had gone missing.➁ The Berserk had been serving as a support vessel for a notorious Norwegian obsessive named Jarle Andhøy, a man with a habit of making trips to high latitudes without official sanction. Despite the lateness of the season, he and a companion had set out to reach the Pole by motor ski, leaving the Berserk moored with a support crew of three to await their return.

On February 22, the vessel turned on its distress beacon. The only three ships in the Ross Sea at the time began a search. In spite of harrowing sea conditions, the Khromov began sailing a back-and forth search pattern. The wind rose to hurricane force, and at one point, the ship was sailing through fifteen-meter seas. With the waves looming higher than the bridge, the crew took the rare step of confining passengers to their cabins, both to forestall panic and to prevent injury. The passengers tumbled stoically in their beds and received cold sandwiches as the storm blew on.

The Second Mate on my own voyage, who helmed the vessel during the search, remembers being astonished at seeing the sun come out and the skies clear while the wind and waves still raged around the ship.

Paul Watson, captain of the anti-whaling vessel Steve Irwin, was out in the same storm and describes it vividly:

It was frightening to many of my crew, although I assured them that our ship was more than equal to the challenge. However, the decks and the port side of the ship were coated in thickening layers of brine ice as the spray frozen in the super chilled air and plastered itself against the steel sides and on the decks adding tons of extra weight that had to be compensated for.

Our bow dove into the seas and plowed into the swells with a force that sent shuddering vibrations throughout the ship. Waves crashed against the port side as if we were being kicked by an enraged titan. The temperatures in the food storage area were so low that the cook had to put produce into the refrigerator to prevent it from freezing. Water pipes burst, and everything, including crew, not tied down flew about the inside making every step hazardous.

Two of the crew’s bunks were flooded with freezing water from ruptured water pipes. One of our crew dislocated her shoulder, and another suffered a severe bruise to her arm. It was not a pleasant ride and heading into a storm like that was not practical—but because of the missing Berserk, we had no choice—as mariners we had a duty to respond, and we did.

The Wellington recovered the Berserk’s empty lifeboat, but the yacht and its crew of three were never found.

The danger of operating in the Antarctic is not just a function of weather, but also the extreme isolation of the Southern Ocean.

Two of the French science staff on my own voyage were aboard the MV Explorer when it collided with ice off of King George Island in November 2007. Reached by the BBC, the poor marketing person for the adventure company put it succinctly: “The hull has a hole the size of a fist and the outlook is not so positive for the ship at the moment.”

The outlook became less positive a few minutes later, when the ship sank.

Passengers and crew spent four hours in the claustrophobic life rafts before they could be rescued by the Chilean Navy. Mercifully, no one was hurt. They were lucky the incident occurred in the high-traffic part of Antarctica, near the tip of South America. In a similar incident off East Antarctica, or in the Ross Sea, it might take days for rescue vessels to reach the ship.

So of the 30 staff and crew on my entirely typical voyage to the Ross Sea, at least a dozen had been involved in a serious maritime incident in the Southern Ocean.

The MV Explorer, having a bad day in 2007

The Hodgeman Islands

On Christmas Eve, 2013, the Akademik Shokalskiy arrived at the edge of the fast ice eight kilometers north of the Hodgeman Islands.

The plan for the day was to take three groups of passengers out to the islands for an hour each. Three Argos would travel together in convoy, beginning around 10 AM. Each convoy would carry eighteen passengers, and bring the previous group back, for a total time at the islands of four hours.

The day started inauspiciously. One of the Argos flooded as it was being towed to shore, leaving only two of the vehicles available for ferry duty. Efforts to revive the swamped vehicle consumed another hour and a half. Turney and his team then had to re-work the day’s schedule to reflect the reduced capacity—there would be four convoys, and passengers would stay out for forty-five minutes.

At half past noon ➂, an initial group of eight passengers set out to the islands through rising winds, followed 45 minutes later by a second. The passengers were told they had limited time to spend on the islands before returning, but no one was enforcing the policy, and people wandered off. The weather at the islands was tranquil, there were penguins everywhere, and it was easy to lose track of time.

Back at the ship, the weather was deteriorating. Video from the ship shows snow already blowing off the ice sheet around noon. By early afternoon, the horizon was growing fuzzy, a sign that rising winds could be expected off the continent. Greg Mortimer and Captain Kiselev were both on the ship’s bridge, monitoring the weather.

At this point Mortimer’s concern was not so much that the ship would be iced in, but that the Argos might encounter whiteout conditions on the ice. Captain Kiselev, meanwhile, was watching the radar screen. Ice floes were moving into the open channel behind the ship. The Shokalskiy needed to leave. At 2:30 PM, he made an urgent request to bring all the passengers back on board.

There were now 15 people out at the Hodgeman Islands, including Turney’s young son. While the islands were visible from the bridge, the group's handheld radios were at the extreme limits of their range. For reasons that were never explained, satellite calls to the islands went unanswered, though the phones had worked perfectly on the much longer excursions at Cape Denison.

At 3 PM, an Argo carrying four people returned to the ice edge, where Turney was waiting with the next group of passengers scheduled to go out. According to a thorough report on the day's events by Nicky Phillips and Colin Cosier in the Sydney Morning Herald:

A passenger, who was standing near Turney when Mortimer called the leader from the ship's VHF radio, recalled their conversation: "Chris, [captain] Igor has just said we need to expedite people back from the islands so we can get out of here," said Mortimer. Turney, standing on the ice edge, repeated the message to confirm he had heard right.

"Affirmative," said Mortimer.

"If I take this lot out, how long can we stay?" Turney said.

Mortimer repeated that everybody needed to get back to the ship.

The passenger was stunned by the conversation, even more so when, a few minutes later, Turney loaded an Argo with six passengers and drove off towards the Islands.

Here it may help to understand the pressures on Turney.

The passengers on the ship had each paid over $17,000 for their berth. They had already missed a promised landing on Macquarie Island, the jewel of the subantarctic, due to inclement weather on the voyage down. Except for one lucky volunteer, they never got a chance to see Mawson’s Huts at Cape Denison, the emotional high point of the trip. And Turney had sent his own son to the islands in the second convoy. Under these circumstances, it’s possible Turney felt unable to send this excited group back to the ship.

It’s also possible that the successful excursion to Mawson's huts had given Turney an exaggerated sense of safety. The two 140-kilometer round trips to the huts had been uncomfortable and scary, but they passed without incident. While the crews were prepared for apocalyptic wind conditions at their destination, they had instead run into sunny, tranquil weather—the same weather the shore group was encountering today.

Once at the islands, Turney did not show much urgency. Rather than taking passengers back immediately, he elected to wait for the second Argo to arrive, so the two could convoy together. That Argo arrived with just a driver, bearing another urgent request from Mortimer to return to the ship.

But there were more people at the islands now than could get back in one trip.

Turney asked the three youngest, fittest members of the group to stay behind with him, along with a tent and emergency bag of provisions. As he wrote later in his book, “If the Shokalskiy has to leave urgently, we can always camp out. If worst comes to worst, we can always make it round the coast to Mawson’s huts.” The remaining passengers were sent back to the ship.

The last Argo convoy returns to the Shokalskiy, at approximately 4:30 PM. Photo: Andrew Peacock

But Captain Kiselev had taken the measure of this man, and had no intention of leaving anyone behind on the ice. An Argo was sent back to collect the stragglers. It was 5:35 PM when Turney arrived back at the ice edge. Passengers recall Mortimer and the Russian crew being visibly angry at this point.

Turney describes being stunned by what he found.

I can see the Shokalskiy has pushed her nose into the sea ice. Conditions are deteriorating, and fast. I’m shocked. A katabatic wind is in full flow, pouring off the ice sheet and whipping the open water into a frenzy. I look out and see ice moving beyond the vessel. It’s completely different from what we had at the islands.

Where the hell did all this come from?

It took another forty minutes to stow the vehicles and make sure everyone was on board. Then the Shokalskiy began its run.

“We were short by one hour,” Captain Kiselev told me later. “One hour earlier and we would have been free.”

The wind had pushed great masses of sea ice into the previously open channel. The ship at first followed gaps between the consolidating floes, then tried to prise them apart at the seams, and finally had to resort to bashing and reversing and bashing again. At one point in the night, a piece of ice punched a two-meter gash in the bow, above the waterline.

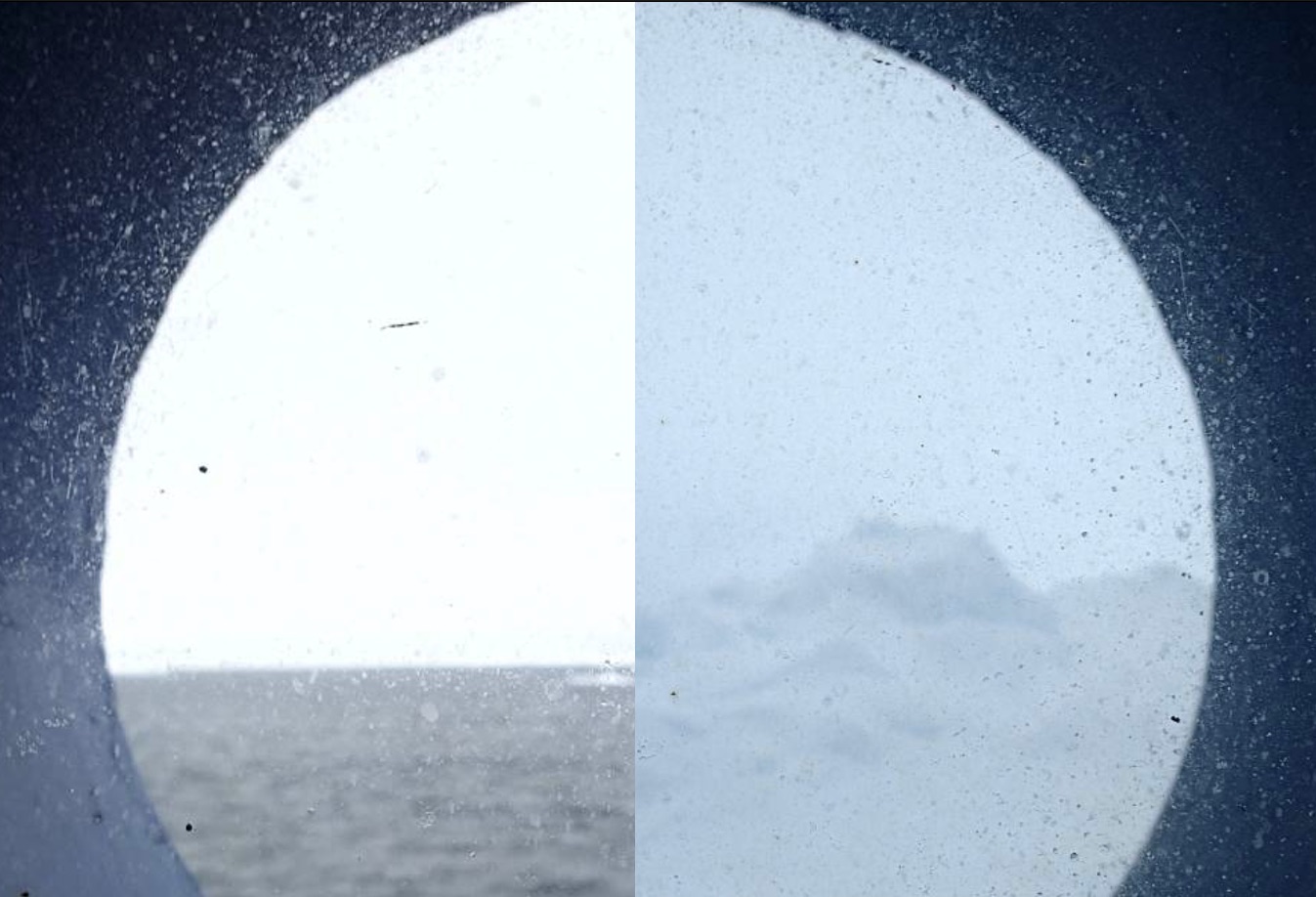

Composite photo taken by a passenger on the Shokalskiy. Left side is the view at 6:02 PM, right side at 6:57 PM

By Christmas morning, the ship was stuck.

Dark patches on the cloud deck showed that open water lay no more than two miles ahead. But the ship was immobilized by ice. At 5 AM, the captain turned off the engines. The Shokalskiy was now a passive observer in its own story.

The situation at this point was not hazardous. That changed when the crew saw icebergs moving near the ship.

Unlike sea ice, which obeys the wind, icebergs follow underwater currents. They can cut through surface ice like tissue paper. While it was unlikely that an iceberg would hit the ship, such an encounter would wreck the vessel and leave the passengers and crew without shelter. So at 8:30 AM, Captain Kiselev activated the ship’s distress beacon.

In an unusual bit of luck, there were three ships close enough to offer help. The Chinese icebreaker Xue Long (Snow Dragon) was on its way to the Ross Sea to scout locations for a Chinese base. The Aurora Australis, the main provisioning vessel for the Australian Antarctic program, was unloading supplies at Casey station about 1,000 miles to the west. A third ship, the French Astrolabe, was also nearby, but it was smaller than the other two icebreakers and less likely to be able to break through.

All three ships diverted to help the Shokalskiy. The Aurora Australis put to sea in the middle of offloading scientific equipment and supplies for the coming research season, taking with it the entire stock of New Year's champagne for the Australian base.

For the next two days, a great storm blew from the southeast, pushing additional sea ice from the Antarctic coast into a thick sheet along the eastern edge of B-09-B. Compression ridges appeared behind the ship, where it was pressed into the ice. The ship developed a slight list. By the time the storm blew itself out, the Shokalskiy was no longer two miles from the water’s edge, but at least twenty.

As the physical storm abated, a social media storm began. Turney had initially tried to keep the ship’s predicament quiet, asking tourists and staff not to alarm their families. He even persuaded the three journalists on board to omit filing reports about the ship being beset. But the official distress call made it impossible to keep the secret. Reporters had started calling the ship, and they were growing dissatisfied with Turney’s prevarications.

Then, disaster struck! The Sydney Morning Herald had published the unthinkable, a short article referring to the Antarctic Ausralasian Expedition as a tourist cruise.

Turney went after this coverage like an Instagram influencer chasing down a bad selfie. Within hours, the immobilized ship had a social media strategy. All descriptions of the vessel as a tourist ship would have to be countered with hard science delivered via “Twitter, Google+, Facebook, Vine, YouTube and the blogs.” Anyone with a satellite phone was encouraged to call home and set the story straight. Those without a phone of their own were assigned office hours when they could come up and make phone calls from the bridge.

Alok Jha, the journalist from the Guardian, helped Turney navigate the unfamiliar shoals of this media landscape.

Alok rattles off a list of networks wanting interviews. CNN, CBS, ABC, BBC, Al Jazeera, SBS, Channel Seven, MTRK, the Weather Channel… the list goes on. I haven’t heard of half of them.“I’ve never seen anything like this. It’s so big we’re even on Buzzfeed, and that’s just made it bigger.

“Really? It’s actually been picked up by them?”

Buzzfeed looks at what’s trending on social media and then pullls it together into a news report. It’s big news if it’s on Buzzfeed.

The only way to control the developing narrative, Jha explained to Turney, was to fill the news vacuum. A university student was deputized to start making daily video diaries. Turney spent hours of every day giving interviews. Science on the ship intensified.

The expedition's public image was also retooled to take advantage of the change in circumstances. No longer would the Australasian Antarctic Expedition be following in the footsteps of Mawson. It had leveled up by becoming trapped in sea ice, and could now follow in the footsteps of the greatest Antarctic explorer of all time—Shackleton himself.

Shackleton

Ernest Shackleton is one of those genuinely admirable people, like Nikola Tesla or Frida Kahlo, who are somehow diminished by the embrace of their posthumous admirers. I think of this as Rick and Morty syndrome. You love the original, but then you look around in horror at the people enjoying it with you and think—is this me? These people are awful! Will I become one of them?Shackleton's immortal achievement is his rescue of the crew of the Endurance after it became beset by ice in 1912, one of the great feats of human endurance and clear-headedness.

The Endurance was frozen in while attempting to land a trans-Antarctic expedition, and the crew spent their first nine months on the immobilized ship waiting for conditions to improve. When the ship was smashed to bits by moving ice, they moved onto the sea ice. When the last floe they could camp on disintegrated seven months later, they fled in boats to a remote island.

And when it became clear that no ship was ever going to visit that island, Shackleton had a boat built, sailed it to South Georgia Island with five men, crossed the mountains with no equipment, and scared the living daylights out of a small whaling community.

Broke, haggard and, let’s face it, a little crazy-looking after wintering on an ice floe, Shackleton talked a succession of people into lending him their ships until he had collected all 22 members of his scattered crew. He didn’t lose a single man in the rescue (though three men died waiting for him in the Ross Sea.)

Apsley Cherry-Garrard, who knew something about Antarctic crises, famously wrote:

For a joint scientific and geographical piece of organization, give me Scott; for a Winter Journey, Wilson; for a dash to the Pole and nothing else, Amundsen: and if I am in the devil of a hole and want to get out of it, give me Shackleton every time.

Today, adventurers, dreamers, and the kind of CEOs who read golf books can’t get enough of Shackleton. A certain kind of ego-driven overachiever has been trying to follow in Shackleton’s footsteps ever since, forgetting that his very first footstep—metaphorically speaking—was straight through the ice.

In 2013, Turney saw a chance to answer a question no one was asking—what if Shackleton had had a Twitter feed?

Relative positions of the Akademik Shokalskiy (UBNF) and Xue Long (BNSK) in the ice field on December 28. "CB" marks the rough location of Mawson's huts; the Hodgman islands are to the right of "WB". The Aurora Australis would arrive later in the black open water to the east.

The Xue Long was the first rescue ship to arrive on the scene, appearing as a red dot on the horizon on the morning of December 27. The plan was for the powerful Chinese icebreaker to crush a path toward the Shokalskiy, which could then follow it back out to open water. But as the morning wore on, the red dot slowed and stopped, still ten miles away. The Chinese captain sent an email apologizing that the ice at his present position was too thick for the ship to penetrate. He offered to keep station while both ships waited for the Aurora Australis.

Stranded in the ice, the passengers kept spirits up by keeping themselves busy. Unfortunately, the bikini selfies, sing-alongs, and videos of frolicking the ship’s company posted to YouTube did little to endear them to a scientific community whose scientific cargo and New Year’s champagne had been left aboard the Aurora Australis. A rollicking New Year’s celebration went over particularly poorly. Researchers at Casey Station and elsewhere were left wondering whether they had sacrificed a season’s worth of research to save a party ship. What the passengers imagined they were posting in a spirit of defiant courage came across as frivolous to a cranky and involuntarily sober science community.

On December 30, the Aurora Australis arrived off the ice pack, and made two abortive attempts to get closer. The Shokalskiy was now some 12 miles from the ice edge. The Xue Long was still on the horizon, not moving. Its captain had not declared that the ship was beset, but for a ship that had full freedom of movement, it was keeping awfully still.

On New Year's Eve, Turney and the two journalists showed up on the big screen on Times Square, bantering with Anderson Cooper and Kathy Griffin before an audience of millions:

TURNEY: [tries to offer a sweater to the camera]

COOPER: They celebrated New Year's six hours ago and I think they've been drinking.

COOPER: Have you been imbibing spirits, because it looks like some of the folks in that video are kind of red in the face?

TURNEY: Just a little bit of champagne. Little bit.

JHA: I don't want to tell tales, but there has been alcohol on the ship and—well, you know, what do you expect us to do? We're out there, we're alone from everyone else. We have to drink something.

COOPER: There's certainly no shortage of ice for your drinks. You can keep it nice and cool. You guys are waiting for a helicopter, but I've never met people who are jollier and happier

GRIFFIN: It's Sex in the City, having mimosas! Which one's Carrie?

COOPER: You guys are really keeping up morale.

Cabin fever among the regular Shokalskiy passengers was climbing to dangerous levels. A few of the passengers had built a 'theme park' in the snow, complete with a snow slide. There had already been choral music, and there threatened to be more.

On January 2, passengers spilled out onto the ice and erected a large blue and orange tent, proclaiming the First Antarctic Writers’ Workshop. Guided by a shipboard historian, many of the participants were making rapid personal breakthroughs in journaling, poetry, and personal memoir when the helicopter came.

The decision to evacuate came easily. Flying conditions were good, the Shokalskiy was low on supplies, and the Aurora Australis was available to take the tourists and scientists to safety. With no immediate prospect of a breakout, a brief helicopter flight seemed safer than leaving everyone stuck indefinitely in the ice. The Russian crew were offered berths as well, but elected to stay with their ship.

The passengers traced out a large circled H on the ice with soy sauce and milo (a distant chocolate relative of Marmite). Half-hovering over the mark, the Chinese helicopter dropped engineers and wooden boards to firm up the landing platform. Once the helicopter could land, the passengers embarked in groups of ten, on a twenty minute flight past the stranded Xue Long to an ice floe alongside the Aurora Australis.

In his book, Turney explains that the decision to leave the ship tortured him. Initially he felt he must stay on board, for science.➃ “Over the last couple of days, I’ve started thinking about remaining with the ship and continuing the science if the others are helicoptered out.“ But his wife talked sense into him. How could he abandon his passengers to an unknown fate? How could he put himself at such great risk? And Turney relented.

“Annette is absolutely right. I’m letting my desire to carry out science muddy my first priority. Everyone needs to get home, safely, together. Just as Shackleton would have done.”

So Turney packed up the fiberglass dog, put his family on the helicopter, and left the Russian vessel behind.

"I can't help but think of Igor and the crew," Turney would later write about helicoptering away from the ship, "Poor bastards. I wish we were all getting out of this together."

The Russians

I asked Dima, the Third Mate on the ship, how all this drama had felt from the crew’s perspective.

“Did you feel you were in danger?”

“No. The main concern was running out of water, and to some extent food. We knew the crew could just eat canned herring. But the passengers would not have been comfortable, and there wasn’t enough drinking water.” ➄

“So there was no danger from being stranded?”

“The only thing we were worried about was icebergs. If one came right for us while we were stuck, it would have crushed the ship. In fact, there was a small hole in the hull up front from the ice”;

“I thought you said you were never in danger?”

He shrugs and smiles.

“What was your plan if an iceberg crushed the ship?”

“We had our go bags ready. We would have hiked inland to the Mawson huts, and then across to the Dumont D’Urville station [about 100 miles west]. We would have been fine.”

Dima makes it sound easy, but storms along this entire stretch of coast can blow for weeks, reducing visibility to nothing. People have gotten lost in such conditions trying to walk ten paces from their tent.

“Did you feel abandoned when the passengers left the ship?”

“No; it was a relief not to be responsible for them. We knew we could fend for ourselves.”

I ask some of the other Russian crew members their opinion of Chris Turney.

“He was constantly smiling, smiling at everyone. His staff was good. But he was not a serious person.”

With the passengers gone, the Shokalskiy grew tranquil. The Russian sailors did not start a writers’ workshop. They skied and tried their hand at ice fishing.

Dima made friends with an Adélie penguin, who strode across the ice every day to see him. There is a strict rule mandating that humans keep 15 meters away from Antarctic wildlife, but the penguin either didn’t know about it, or chose not to comply. He wanted fish.

“I wore gloves to pet him. They don’t like being touched by warm hands.” The Adélies look fuzzy, but their feathers are harsh and stiff. Unlike the royal penguins that live further north, Dima said, they refuse potato chips and accept only fish, which they smell strongly of.

Ten days later, the interspecies friendship ended. A shift in the winds opened a long fissure in the pack, and both the Shokalskiy and the Xue Long were able to reach open water under their own power. The Shokalskiy was back in port in New Zealand before the rescued passengers on the Aurora Australis had even left Casey Station.

No one was happy with the events of that summer. The Australian government started efforts to recoup the $2.4M rescue cost from the expedition’s insurers. The ship's passengers spent a long three weeks as supernumeraries on the Aurora Australis, trying to stay out of the way as the crew finished unloading at Casey Station. Many sent faxes of gratitude to the Xue Long and Akademik Shokalskiy while those ships were still stuck in the ice.

Some of the ship’s passengers were philosophical; others resentful that a couple of hours on an Antarctic island had cost them a month’s delay in getting back to Australia. One called the shaky way the expedition had been organized a "boy's own adventure on the ice".

Scientists across Antarctica were angry at the disruption to their research programs. While science on the AAE was presented as a carefee, flexible activity that could be pursued anywhere, their own plans had been years in the making and required keeping to a meticulous timeline. The expedition's somewhat grandiose claims around its own scientific contributions did not help.

Chris Turney published a letter in Nature rather cheekily citing the ship’s social media follower count as evidence of how well the ship's voyage, and implicitly its stranding, had served the interests of the Antarctic research community. The head of the Australian Antarctic Division replied with his own letter to Nature disavowing Turney’s insinuation that the AAD had in any way endorsed his scientific program.

Antarctic tour operators, meanwhile, were mortified that at a ship from outside their fraternity had Leroy Jenkinsed its way into some of the worst ice conditions on the planet with children aboard, threatening a tourist industry that already has an uneasy relationship with Antarctic science.

The Russian and Chinese crew did not relish being put in circumstances where they had to request help from an American icebreaker—the massive Polar Star, which began lumbering south to help in early January. Fortunately, the Americans were still a long ways off when the two stranded ships broke out on their own.

Chris Turney photographed at Mawson's huts.

Turney wrote a book about his experience, which I have drawn on extensively here. The book is not subtle—the New Zealand edition is even called Shackled. In it, Turney interleaves his story with Shackleton’s epic, almost page by page.

For as much as he wanted to be Shackleton,though, what the 2013 Antarctic Australasian expedition really turned into was a burlesque of Robert Scott. The use of science as a fig leaf for ambition, lack of safety margins, elaborate plans that changed moment by moment, unclear lines of responsibility, and obsession with how the story would play out in the media back home were all vintage Scott.

Both Scott and Turney counted on everything to go right, and when it didn't, became convinced they had encountered once-in-a-lifetime weather conditions that absolved them from any responsibility. Even the loss of a key motor vehicle as it was being brought to shore seemed to be a call-out to the Terra Nova Expedition.

Still, there are limits. For all the social distance between Scott and his crew (who built a wall of crates to separate themselves from the officers in their shared hut), Scott at least spoke their language. And Scott would never have brought his kids to Antarctica.

Expedition organizers Chris Fogwill and Chris Turney

According to Captain Kiselev's report, on the morning of December 25, icebergs came within two cable lengths—370 meters—of the immobilized Akademik Shokalskiy. If the ship had been hit that day, the ensuing oil spill would have been the worst environmental disaster in Antarctic history, and perhaps spelled the end for all tourism in the region.

Luckily, no one was hurt during the ten days the Shokalskiy spent beset by ice. But Chris Turney and Chris Fogwill came close to committing the ultimate Antarctic sin—ruining it for everyone else. One difference between our time and Shackleton’s is that no one will be ever again be left to fend for themselves on the ice. There will be search and rescue efforts, no matter the cost, even if they derail an entire summer of research.

But this can only happen so many times before the continent is put off limits to all independent visitors. Through his carelessness and imprudence at the Hodgeman Islands, Turney brought that day one step closer, doing a disservice to anyone who dreams of Antarctic adventure.

➀ The traditional nerd story is that Mertz died of Vitamin A toxicity, but this has been challenged by more recent scholarship.

➁ In some accounts, the Professor Khromov is referred to as the Spirit of Enderby. They are the same vessel.

➂ Turney's book says the trips started at midday. I'm relying here on the account by Philips and Cosier, which I believe is more reliable.

➃ It's not clear what science was being done on the ship at this point. By my count, there were ten scientists on the ship: four marine biologists, two geologists, an oceanographer, an ornithologist, and two climatologists. Once it was stuck in ice, the Shokalskiy could take temperature readings and birdwatch, but not much else.

➄ It may be surprising that fresh water was a limiting factor on a ship surrounded by ice. It takes several years for the pockets of brine to leach out of sea ice and render it drinkable when melted. Younger sea ice is brackish.

Further reading

You want longform? I'll give you longform. Previous posts in this series:

Shuffleboard At McMurdo

Cape Adare

Gluten-Free Antarctica

Other things to read:

- Stuck in the Ice is a detailed chronology (with video) of the day of the stranding by Nicky Phillips & Colin Cosier.

- There is a wonderful account of l'affaire Shokalskiy by Jon Tucker, one of the volunteers on the expedition and an accomplished Antarctic sailor.

- Andrew Luck-Baker, who was a journalist on the expedition, published his own account for the BBC: Why did Antarctic expedition ship get stranded in ice?

- Chris Turney's book is called Iced In: Ten Days Trapped on the Antarctic Ice. Please borrow this from the library rather than buying it. It would hurt me to know I had put money in the guy's pocket.

- Turney also wrote a short account for the Sydney Morning Herald called How my Antarctic scientific expedition became a fight for survival

- Here is Turney's letter to Nature (This was no Antarctic pleasure cruise), and the icy response from the head of the Australian Antarctic Division (Polar rescue: science was not well served).

- If you are a complete masochist, you can read the love letters of Douglas Mawson and Paquita Delprat. Delprat was a sheltered society lady who spent the first months of Mawson's absence worrying she might be pregnant from the passionate goodbye kiss she shared with her departing fiancé.

- Shackleton's memoir of his expedition, South!, may be the greatest Antarctic memoir. The story is completely impossible, exept it happened.

- Mawson's memoir of his expedition, Home of the Blizzard, includes accounts from multiple participants.

| « Microsoft's Hypocrisy on DACA | Who Should Secure Congressional Campaigns? » |

brevity is for the weak

Greatest Hits

The Alameda-Weehawken Burrito TunnelThe story of America's most awesome infrastructure project.

Argentina on Two Steaks A Day

Eating the happiest cows in the world

Scott and Scurvy

Why did 19th century explorers forget the simple cure for scurvy?

No Evidence of Disease

A cancer story with an unfortunate complication.

Controlled Tango Into Terrain

Trying to learn how to dance in Argentina

Dabblers and Blowhards

Calling out Paul Graham for a silly essay about painting

Attacked By Thugs

Warsaw police hijinks

Dating Without Kundera

Practical alternatives to the Slavic Dave Matthews

A Rocket To Nowhere

A Space Shuttle rant

Best Practices For Time Travelers

The story of John Titor, visitor from the future

100 Years Of Turbulence

The Wright Brothers and the harmful effects of patent law

Every Damn Thing

Your Host

Maciej Cegłowski

maciej @ ceglowski.com

Threat

Please ask permission before reprinting full-text posts or I will crush you.